I’m delighted that the Museum of Russian Icons has posted on their youtube channel their recent zoom presentation by MIT Russian historian Elizabeth Wood and me:

My own presentation begins at about 31:30.

I’m delighted that the Museum of Russian Icons has posted on their youtube channel their recent zoom presentation by MIT Russian historian Elizabeth Wood and me:

My own presentation begins at about 31:30.

Columbia University’s Harriman Institute for Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies is currently exhibiting my art about Russia, in PEASANTS, CLANS, AND EFFERVESCENT ABSOLUTISTS! Sept. 4-Oct. 18.

Please join us for the exhibit reception Sept. 20, 2018, 6-8 pm in the Harriman Institute Atrium. More information is here.

I will give an artist lecture in the Atrium Oct. 2, 2018, at 6 pm. More information is here.

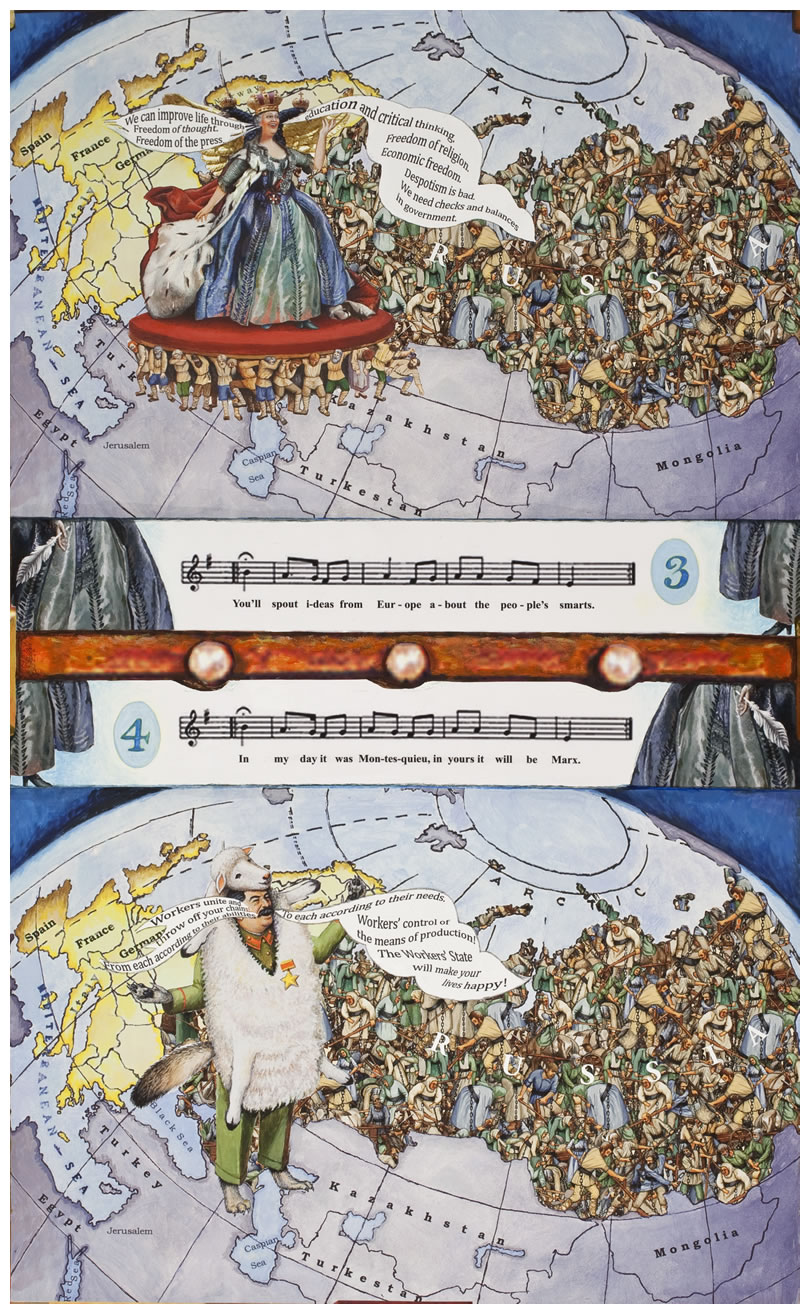

This is part of a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. (The first, Introductory Study Guide is here).

In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

_____________

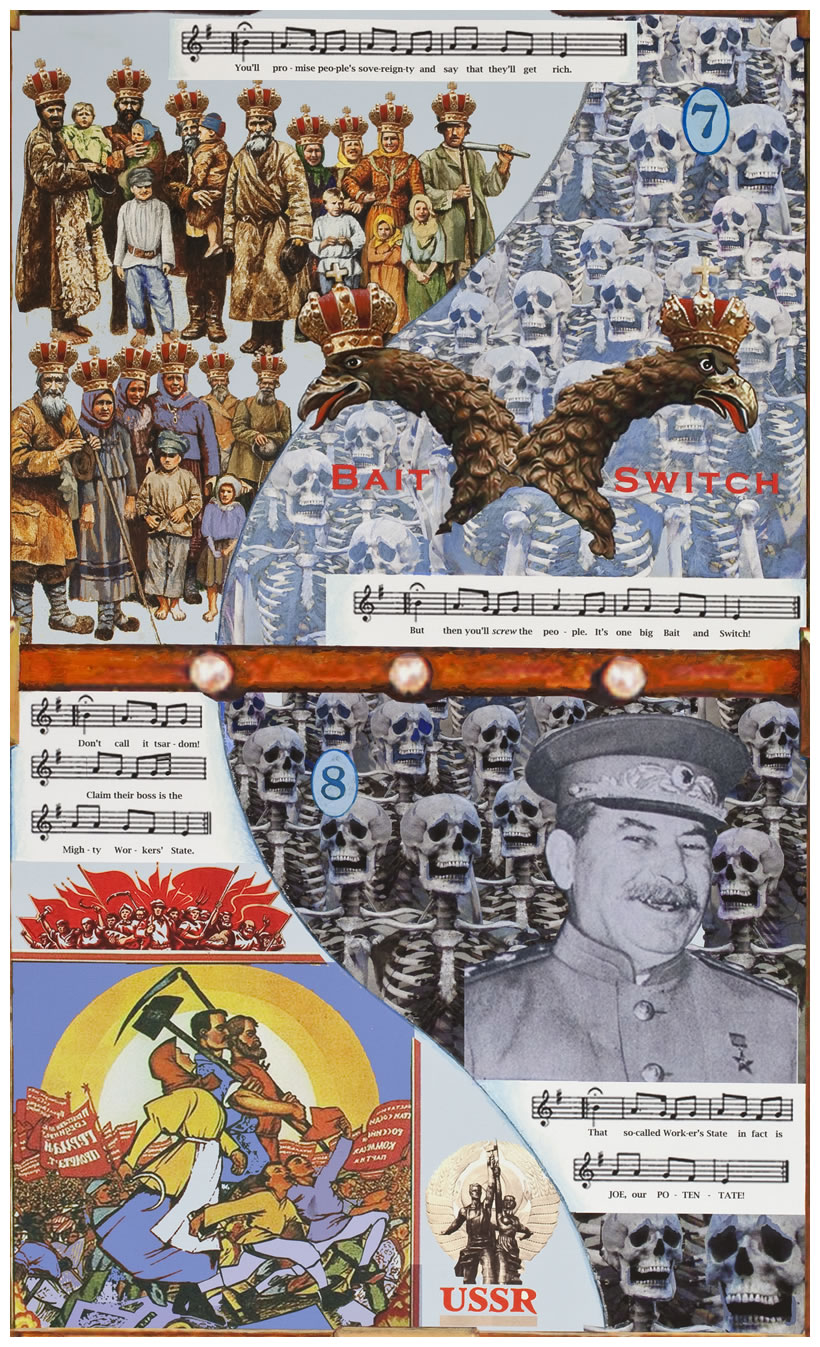

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution destroyed tsarism and instituted a radical new social order, Soviet Communism.

Or did it?

Beginning soon after the Russian revolution, “Communism” became the 20th century American boogeyman. China had its revolution in 1949, and many in the US saw Communism as a world-wide plague that might infect whole chunks of the globe. We went to war in Korea and Viet Nam to try to stop it.

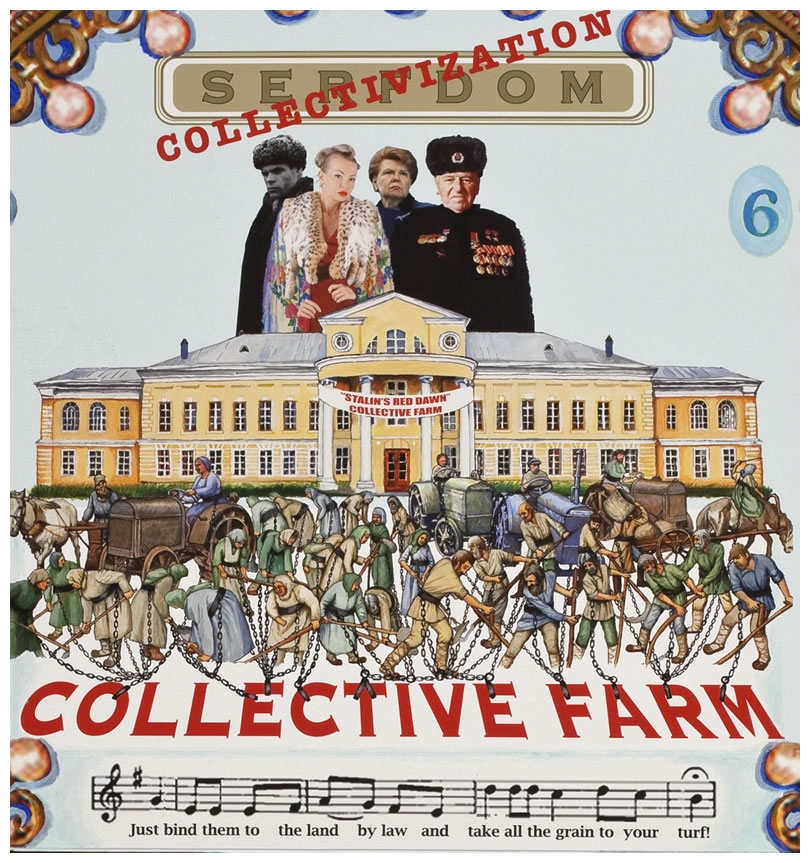

For peasants – who made up more than 80% of Russia’s population in 1917 – the central, defining element of Communism was the collectivization of agriculture. Peasants were forced to become members of large collective farms on which they (at least in theory) tilled the land jointly, gave most of the crops to the state, shared the rest, and lived mainly off what they grew in small “private plots” in their yards.

Well, the Cold Warrior might say, wasn’t that just like those dictatorial, commune-loving Commies, taking away people’s private property and telling them what to do?

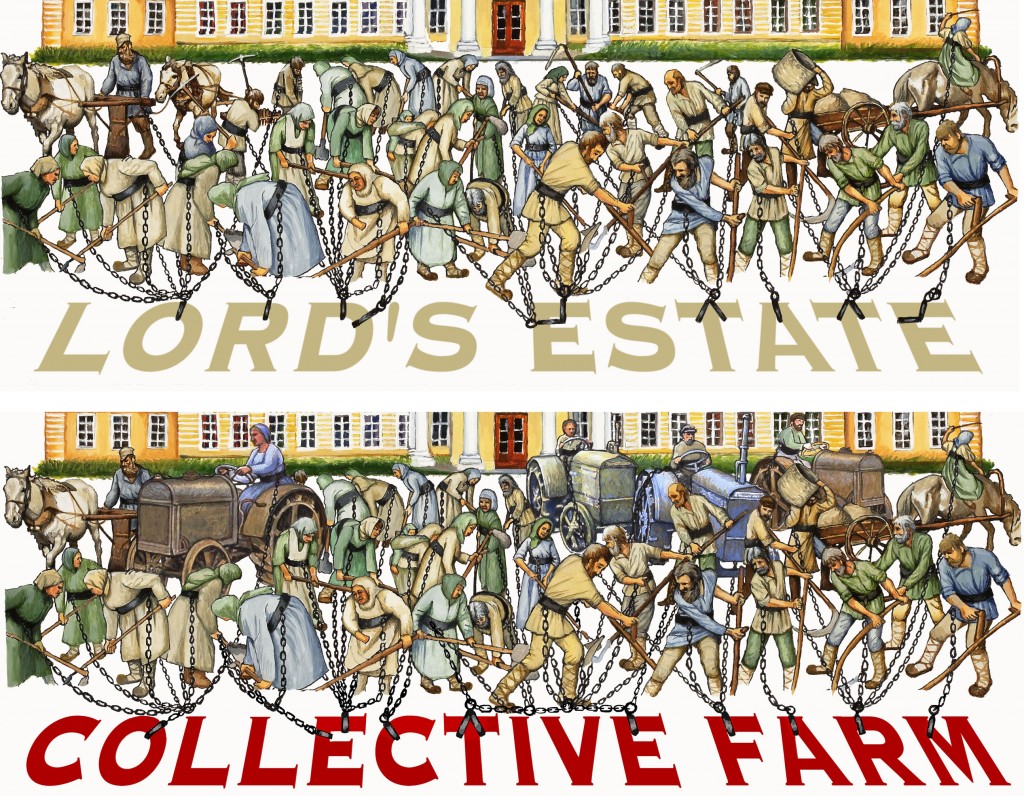

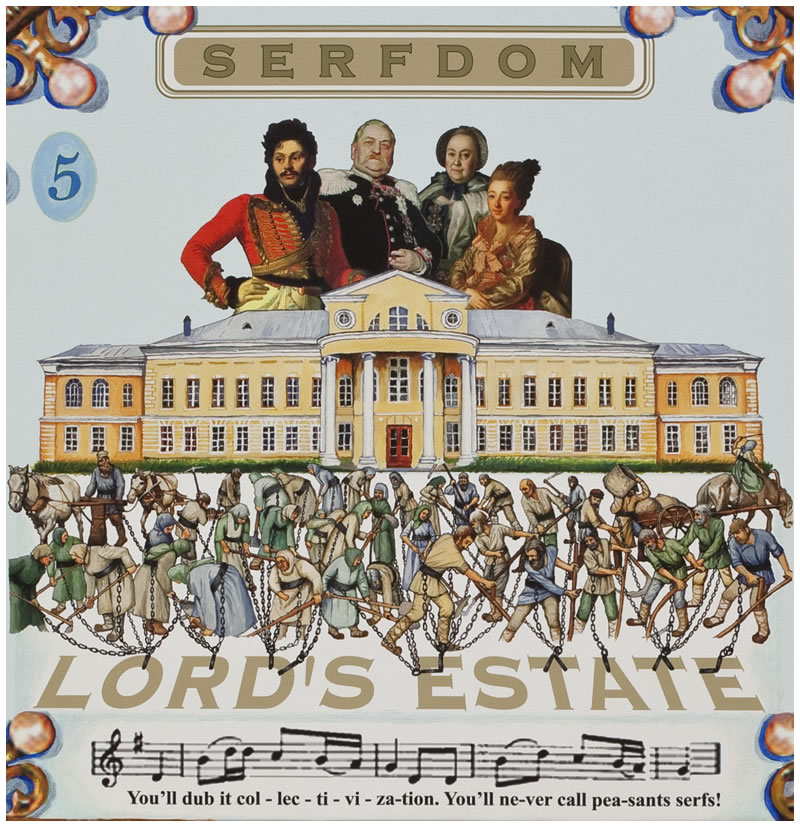

Well, actually…many Soviet peasants felt collectivization was a return to serfdom. Lynne Viola, in Peasant Rebels Under Stalin, writes that as peasants were forced into collective farms (“kolkhozy” in Russian), they “rebelled against what many called a second serfdom….” (p. 3; my emphasis)

Under tsarism, serfdom had bound peasants to their lords’ estates for life. They were obligated to work on the serfowner’s estate and/or pay their lords either in kind or cash.

Serfdom lasted for centuries in Russia; it was legally abolished in 1861, within decades of the end of tsarism.

Discussion Question:

Was collectivization part of a revolutionary new ideology, Communism? Or was it essentially a return to serfdom? (continued below images)

Can you pinpoint the similarities and differences between my painting/collage above and the one below?

Sheila Fitzpatrick’s superb Stalin’s Peasants: Resistance & Survival in the Russian Village After Collectivization observes that the analogy of collectivization to serfdom

“…had some real applicability, especially the analogy with barshchina (where the serf’s obligations were in labor rather than money). The argument underlying the analogy ran as follows. On the kolkhoz [collective farm], as on the old master’s estate, peasants were obliged to spend at least half their time working in someone else’s fields (meaning the kolkhoz fields) essentially without payment. They lived on the produce of their own small plots, but constantly had to struggle for enough time to work on them. As in the days of serfdom, they did not have the right to leave the village for work outside without permission. This implied that kolkhozniks belonged to a special category of second-class citizen, just like serfs. They were obliged to perform corvée obligations to the state. It was not unusual for local officials, kolkhoz chairmen, and brigade leaders to assume the prerogatives of estate owners and their stewards under serfdom, subjecting field peasants to beatings and insults.” (p. 129)

Ownership of agricultural products the peasant produced: According to David Moon’s essential The Russian Peasantry ,

“In the last century of serfdom, it can tentatively be concluded that Russian peasants were compelled to hand over to the ruling and landowning elites around half of the product of their labour.” (Moon, p. 88)

Under Soviet Communism, most of what was grown on the collective farm had to be turned over to the Soviet state. The amount remaining was distributed among the kolkhoz members, but it was typically so small they had to mainly live from their “private plots,” which they struggled to find time to work (Moore* p. 85). Sowing plans determined by the government dictated what was grown even on private plots (Fitzpatrick, p. 132-3).

Under serfdom, peasants’ role had been similarly divided: “In many Russian villages…under serfdom, the master’s land and that of the village were adjacent or intermingled, and the peasants tilled both.” (Fitzpatrick, p. 21).

Under Communism, even private plot produce didn’t belong completely to the people who farmed it (Moore, p. 86).

“Each household had the obligation – reminiscent of the obligation of the serf household to the lord in earlier days – to deliver meat, dairy products, eggs, and other produce from the private plot to the state. Under state procurement regulations, first introduced in 1934, every kolkhoz household…was required to deliver a quota of meat and milk, even if it did not have pigs or sheep to slaughter or a cow to milk. This was a subject of great peasant resentment and complaint.” (Fitzpatrick, p. 132)

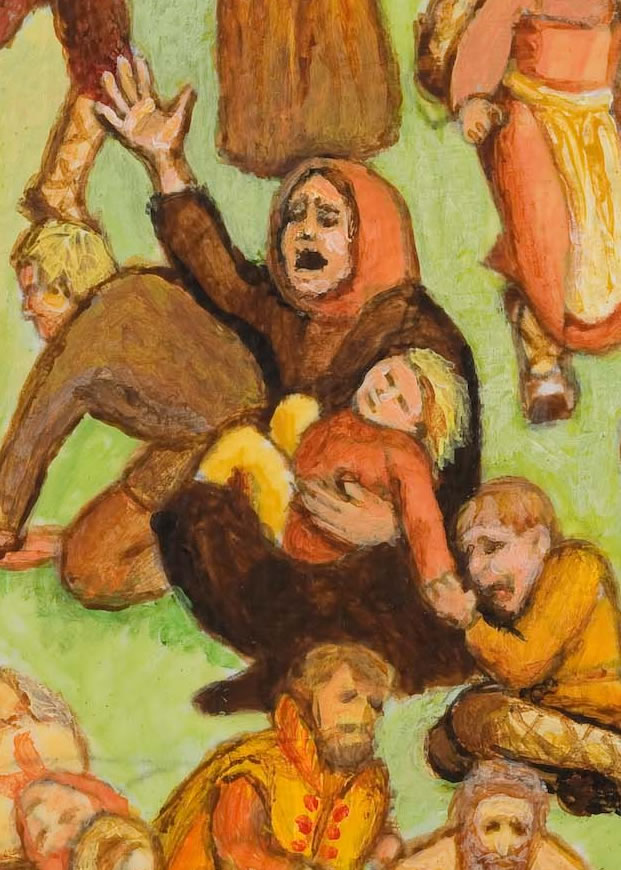

Details of SERFDOM and COLLECTIVIZATION, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Organization of work: Fitzpatrick notes that under collectivization,

“Where the brigade system really functioned, organization of field work appears to have been similar…to a big estate in the old days of serfdom. According to one contemporary description of a large grain-growing kolkhoz in the south, villagers were awakened by a bell at 5 A.M. and were required to present themselves in front of the administration building an hour later for the day’s instructions. The brigade leaders met each evening with the kolkhoz chairman and other kolkhoz officers to plan the next day’s work….” (p. 146).

The Harvard Project’s** postwar interviews of Soviet refugees (methodology p. 11-12) revealed “the peasant’s inexorable opposition to the regimentation of his activities by the collective farm.” (p. 123)

“…the peasant emerges as the ‘angry man’ of the [Soviet] system, …convinced of his exploitation, resentful of his deprivation of goods and opportunities, and outraged by the loss of his autonomy. (p. 254)

“Centrally and overwhelmingly they want the collective-farm system done away with in its present form, because they see it as enslaving the peasant and making him a serf of the state.” (p. 215)

Corvée obligations: Under Communism, peasants owed a certain number of days each year to the state for work to build/repair roads, and cut/transport timber. As Moon describes, serfs had owed similar work

“obligations to their local authorities. They were required to construct and maintain roads and bridges, and to supply horses and carts to transport officials, the mail, troops and prisoners.” (Moon, p. 86)

The right to choose how/where to live/work: An internal passport law was passed in 1932, after which citizens couldn’t change their place of residence or job without government permission. Similarly, under tsarism, serfs had not been permitted to move away from their masters, nor could they take up another line of work on their own volition. In fact, the tsarist government held tight central control over all industry in the Russian Empire. Individual entrepreneurship was not permitted outside tsarist state dominance.

Ownership of horses and tractors: At the core of Soviet reality was the state’s fierce push to industrialize and mechanize a vast, overwhelmingly backward rural economy. As shown in my second painting (see above), COLLECTIVIZATION, in agriculture, this meant tractors. Tractors were owned by the state.

But in fact, agriculture remained largely unmechanized for many years (which is why, despite the addition of some tractors in my painting, most peasants are doing exactly the same kind of labor as in my SERFDOM painting). Horses were used for plowing, hauling, and transportation, but there were far too few in the USSR for the level of need. Peasants had to get permission to borrow horses for their own necessities (including on private plots), and then, if lucky enough to get it, had pay for the animals’ use.

So we’ve discussed the bottom half of my paintings SERFDOM and COLLECTIVIZATION. But what about the top parts, those people above the manor house, transformed into “Stalin’s Red Dawn” Collective Farm in COLLECTIVIZATION? Who are those people, and how are they similar or different? (continued below image)

Both serfdom and collectivization were designed to extract agricultural produce from the countryside to support the unusually heavy requirements of a non-agriculturally productive bureaucracy, military, government, and urban areas.

Beginning with the early centuries of the rise of the Russian state, its protection required that an unusually large proportion of its resources be devoted to the military, for reasons explained here, here, and here. Peter Kolchin*** wrote that serfdom arose in Russia because, under conditions of extremely low agricultural productivity and labor shortage, the tsar’s fighting noblemen needed unfree labor to provide them food, clothing, and other necessities (p. 22). Landholders,

“whose principal obligation to the tsar was to fight in his wars, were to be supported by the peasants who lived on their estates, and land grants typically…instructed [serfs] to ‘obey’ their new landlord, ‘cultivate his land and pay him grain and money obrok…. [L]andholders…were absent in military service much of the time [so they] depended for their livelihoods on ‘their peasants…” (Kolchin, p. 5)

Soviet Communism used collectivized farm labor to enable its drive to industrialize a backward, overwhelmingly peasant economy within a few decades – a process that had evolved organically over centuries in Western Europe.

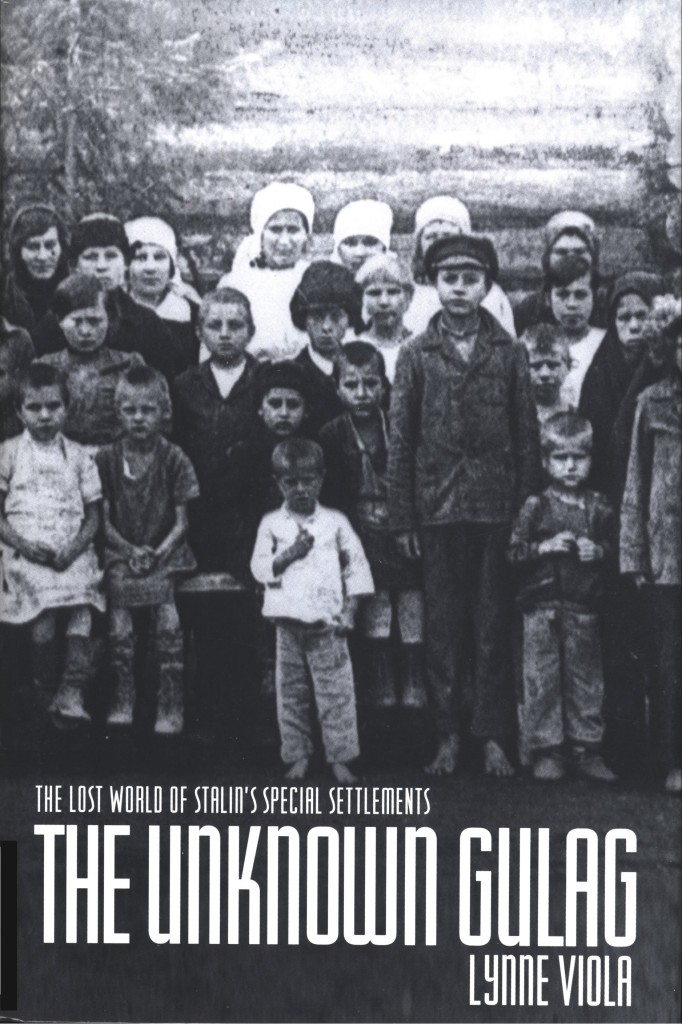

“The Soviet Union under Stalin was, in essence, an extraction state, characterized by extreme centralization and the total mobilization of resources (including labor) in the interests of state building and economic development…. Under Stalin, the peasant majority served as the fulcrum of modernization in what was one of the most radical transformations in modern history.” (Lynne Viola, Unknown Gulag, p. 185)

Under both serfdom and collectivization, there were agents who compelled peasants to work. Tsarism and Soviet Communism were autocratic, hierarchical structures, so the the lives of the agents in both systems were structured by their national government. The position of each, however, provided a range of opportunities for wealth and power over underlings. (Fitzpatrick weighs the rewards and risks of holding local positions of authority p. 194).

“The managerial style of the kolkhoz chairmen and state-farm directors…had similarities to that of landowners and estate managers in the old days, and the peasants’ behavior to them, similarly, had much in common with the serf….

“Kolkhoz chairmen…were the…wheeler-dealers of the rural scene…. [They] were masters of their own small fiefdoms, cultivating contacts in the raion [county] and beyond, and making ingenious deals….” (Fitzpatrick, p. 316)

Lynne Viola's THE UNKNOWN GULAG explores the far northern settlements of the "unknown GULAG" as loci of slave labor to support the USSR's rapid industrialization.

Moore wrote about one type of rural Soviet official:

“In the internal organization of the kolkhoz the major figure is the chairman. His role is characterized by heavy obligations and limited authority. The key decisions concerning agricultural processes, plowing, sowing, and harvesting, come to the kolkhoz from the outside. The chairman’s duty is to see that they are carried out, and that the quota of obligatory deliveries to the government is met. To enforce his orders he has certain powers of punishment and reward, ranging from the authority to order a piece of work done over without pay to conferring prestige and financial benefits on those who exceed the planned quota.” (Moore p. 81)

The top dogs in my SERFDOM represent the lord of the manor and his family, who in large part dictated their serfs’ daily lives. I carefully selected these particular images from many portraits of the Russian nobility that I’ve spent a lot of time collecting. I chose the most evocative portraits from my collection.

The top dogs of my COLLECTIVIZATION represent a few of the various types of collective farm bosses who determined much of the daily lives of peasants under Communism: the kolkhoz chairman and local party and soviet officials. These might include, as I’ve portrayed them from right to left:

Perhaps the most important difference was that, under serfdom, a large share of their produce usually went to the landholder of the estate on which the serf worked – though for example, Peter the Great took more from the peasants than did serfowners. At its height, Peter’s taxation policies “severely restricted the amounts of money and labour landowners could get from their peasants.” (Moon, p. 87) Under Soviet Communism, the state controlled the disposition of agricultural produce.

Mechanization: As shown in my second painting above, the central focus of the Soviet state became modernization and industrialization. To the extent possible, tractors and combines were introduced into the countryside.

Moving to urban areas: Because of the Soviet stress on industrialization, and the relatively small urban labor force, collective farm members were much more often permitted to leave the farm to become factory workers or receive training in other fields.

Stratification and unequal pay: Serfdom had imposed a large degree of homogeneity on Russian peasants. Steven L. Hoch’s wonderful Serfdom and Social Control in Russia demonstrates why it was to the advantage of serf owners to actively maintain equality among peasant households (p. 104-27). Under Soviet Communism, however,

“Although the kolkhoz was theoretically a cooperative organization of equal partners, its internal structure quickly became stratified. The stratification, based on the type of work performed by kolkhoz members, was something new in the village….

“Two privileged strata emerged in the kolkhoz of the 1930s. The first was the ‘white-collar’ group: the kolkhoz chairman, members of the kolkhoz board, the accountant, the brigade leaders, the business manager, and an evergrowing list of other offices (head of the warehouse, head of the club, head of the reading room, director of the choir…) that the kolkhoz administrators awarded to their relatives and friends…. The second stratum was the skilled ‘blue-collar’ group of machine operators…, including the modern occupations of tractor driver, combine operator, and truck driver….” (Fitzpatrick, p. 139-40; see also Moore p. 83)

Lynne Viola argues that “It is unlikely that peasants actually believed the collective farm to be a return to serfdom per se. Serfdom rather served as a metaphor for evil and injustice.” (p. 60. See also Fitzpatrick p. 313 for how this may have differed over time).

Discussion questions:

In what specific ways did collectivization differ from serfdom?

As you weigh the similarities and differences between serfdom and collectivization, how would you characterize the historical process? Would you call it revolution or evolution? Or can you find another more accurate term?

Thought question: What does this say about how social change occurs? Do revolutions ever truly happen? Can you think of examples? What about parallels with today’s “Arab Spring?” Are the milestones we often note – such as the abolition of slavery in the US or of serfdom in Russia – truly radical changes, or do they tend to be simply legal markers along what in fact is a slow process of evolution? In this context, Sheila Fitzpatrick’s description of how serfdom lingered even after it was legally abolished in 1861 is powerful:

“…peasants had many things to remind them of serfdom. Collective responsibility for redemption payments inhibited the departure from the village of individual peasants or households, thus perpetuating the restriction on mobility that serfdom had earlier imposed. The nobles who were the peasants’ former masters retained their estate lands…, as well as having considerable residual authority over the local peasants.” (p. 21)

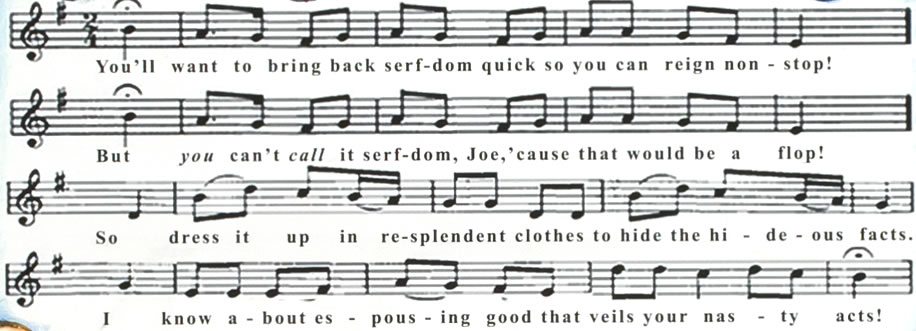

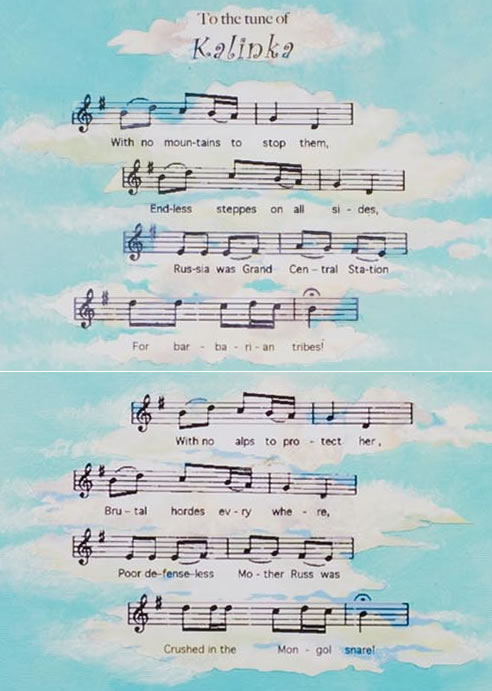

Detail of Catherine the Great's song of blessing to the infant Stalin in DRESS IT UP IN RESPLENDENT CLOTHES, including original lyrics (to the traditional folk tune Kalinka) by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Lynne Viola, PEASANT REBELS UNDER STALIN, Oxford University Press, 1999.

– THE UNKNOWN GULAG: THE LOST WORLD OF STALIN’S SPECIAL SETTLEMENTS, Oxford University Press, 2007.

David Moon, THE RUSSIAN PEASANTRY: THE WORLD THE PEASANTS MADE, Addison Wesley Longman, 1999.

Sheila Fitzpatrick, STALIN’S PEASANTS: RESISTANCE AND SURVIVAL IN THE RUSSIAN VILLAGE AFTER COLLECTIVIZATION, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Steven L. Hoch, SERFDOM AND SOCIAL CONTROL IN RUSSIA: PETROVSKOE, A VILLAGE IN TAMBOV University of Chicago Press, 1986.

* Barrington Moore, Jr., TERROR AND PROGRESS USSR, Harvard University Press, 1954.

** Raymond A. Bauer, Alex Inkeles, and Clyde Kluckhohn, HOW THE SOVIET SYSTEM WORKS, Vintage Books, 1956.

*** Peter Kolchin, UNFREE LABOR, AMERICAN SLAVERY AND RUSSIAN SERFDOM, Harvard University Press, 1987.

An additional terrific book on Russian serfdom is Tracy Dennison’s THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK OF RUSSIAN SERFDOM.

This is part of a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. (The first, Introductory Study Guide is here).

In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

______________

Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV, 1530-84) is infamous for his brutal murders of thousands of his people during the second half of his reign. The most notorious of these killings were carried out publicly in grotesque ways, such as impaling or dousing the victim alternately with freezing and boiling water. Historians have debated whether Ivan was insane during the period he called the Oprichnina (1565-72), or was carrying out a strategy to eliminate encumbrances to his autocratic rule.

Question 1:

Was Ivan the Terrible crazy, or was he carrying out a rationally crafted policy?

I’d like to suggest a third possibility: that whether or not Ivan the Terrible was (at least at times) off his rocker, his murderous actions compeled a leap forward in the same direction as Muscovite rulers before and after him.

After all, even an unbalanced monarch grows up in a particular culture, with particular powerful people and groups around him, absorbing whatever history his mentors teach him about his country and government. Maybe even a mentally unstable ruler’s perceptions and extreme actions are so flavored by the world in which he lives that they move forward its trends even without his planning it.

Question 2:

Might a somewhat imbalanced ruler be able to continue – perhaps in a more ruthless way – trends begun by more stable rulers before him? How would this play out?

This question doesn’t necessarily have a clear answer, but it’s interesting to think about.

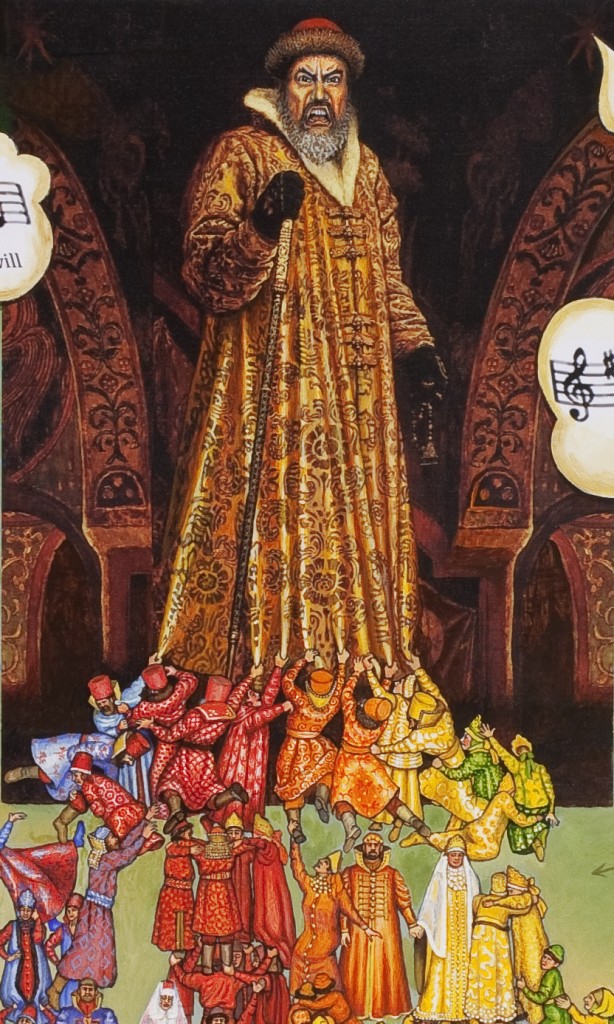

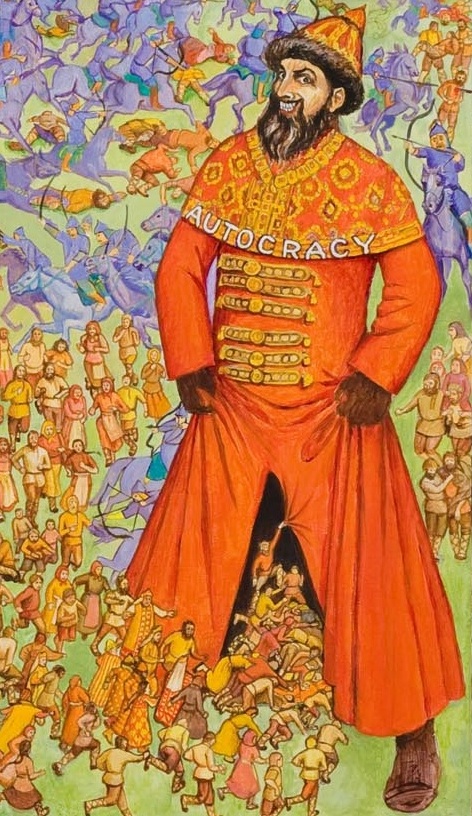

Ivan the Terrible as a fairy godfather giving his blessing to the infant Stalin (Modified detail from DRESS IT UP IN RESPLENDENT CLOTHES, painted by Anne Bobroff-Hajal)

Why should we bother our brains with questions about Ivan the Terrible anyway? Aren’t they only about some looney guy centuries ago in far-off, now-pretty-irrelevant Russia?

Well for one thing, many of Ivan the Terrible’s actions were strikingly similar to those of Josef Stalin 400 years later. In the 20th century, Stalin killed something on the order of 20 million Russians, most of them innocent of the charges against them, also in hideous ways. For example, both Ivan and Stalin executed some of their most devoted supporters. They each killed some of their best generals during or on the eve of major wars. And they each eventually turned the terror against the people who originally led it, executing many of those who had carried out its first phases.

So two Russian rulers who lived four centuries apart both committed similar horrific murders of vast numbers of their populations. Maybe they were both crazy!

But here again, whatever their mental status, their “crazy” behaviors were so strikingly similar that we have to wonder what was in the air in Russia – or the water, the land, or the vodka – that made two rulers almost half a millenium apart do the same maniacal things.

Question 3:

What might caused two rulers of Russia (USSR), living four centuries apart, to visit terror on their own populations in such similar ways?

Again, you won’t be able to respond to this question now. These “Big Questions” Study Guides – as well as my art about Russian history – chip away at these issues, providing ideas and evidence that students can mull over to arrive at their own opinions.

Detail of “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.s,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal: My representation of Ivan the Terrible’s face.

The two most recent books about Ivan the Terrible each provide excellent summaries of the lively ongoing debate about Ivan and his oprichnina by a number of historians in the US, Britain, and Russia. I recommend you read both to get two perspectives:

Isabel de Madariaga, Ivan the Terrible (2008), Forward, pp. x-xiv.

Andrei Pavlov and Maureen Perrie, Ivan the Terrible (Profiles in Power series, 2003), Introduction, pp. 1-6.

Two well-known American historians of Russia make the argument that Ivan IV was mentally ill during the oprichnina:

Robert O. Crummey, author of the superb The Formation of Muscovy 1304-1613, p. 162-72.

Richard Hellie, “What Happened? How Did He Get Away With It? Ivan Groznyi’s Paranoia and the Problem of Institutional Restraints,” Russian History 14 (1987): 199-224.

NOTE: Although I don’t personally agree with Crummey and Hellie on the issue of Ivan’s sanity, they have each written superb books, some of the very finest in the field of Russian history (Crummey’s The Formation of Muscovy and Hellie’s Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy; his research on slavery in Russia is also revelatory).

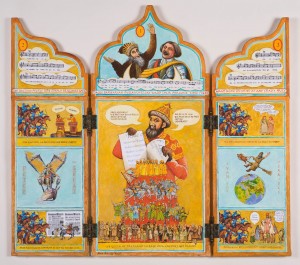

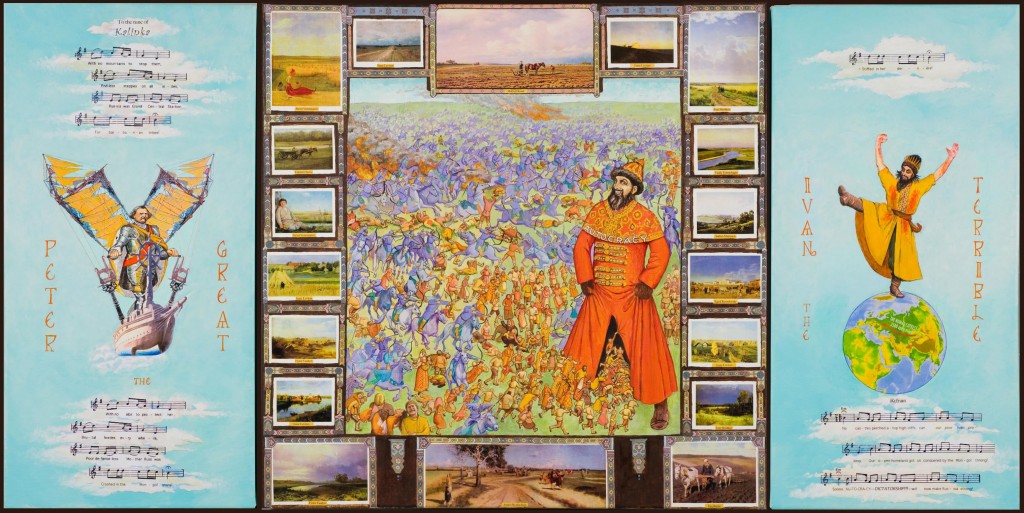

“Your Grasping, Scheming VIP’s,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 32″ x 66″

To decide whether Ivan’s actions were insane, we need to figure out whether there was any possible rationale to them. This doesn’t mean whether his actions were right or wrong (we can probably all agree they were morally heinous). It means we need to investigate whether Ivan himself may been pursuing a comprehensible strategy, however detestable we may find it.

Crummey has described the court in which Ivan the Terrible found himself as a young monarch who wanted the power to dictate without interference from anyone:

“The tsar lived within a spider’s web of family relationships. Ties of kinship or marriage linked many of the powerful court clans – princely and non-titled – to one another. These interlocking family groupings monopolized the highest commands in the army and filled almost all of the places in the Boyar Council [advisory council to the tsar]. Economically, their power rested on ownership of estates held on unconditional tenure. Any Muscovite ruler had to reckon with them when making appointments or charting national policy.” (Crummey, p. 160).

Text continued after next image

Russian tsars, including Ivan IV, didn’t like having to contend with the influence of the “web of clans” of the Russian nobility, portrayed in this detail of my “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.s”

Pavlov and Perrie paint a similar portrait of the obstacles the young Ivan wanted to overcome in his drive for power:

“…the boyars – and especially those of princely origin – retained great influence. The most eminent of the princes continued to own large family estates which were the remnants of their formerly independent principalities…. At court they comprised their own highly cohesive ‘corporations’ – the Suzdal’ princes, and Rostov princes, the Yaroslavl’ princes and the Obolensk princes among them. These corporations were formed on the basis not only of the princes’ common ancestry, but also on their possession of hereditary estates within their former principalities. Although their ownership of hereditary estates did not mean that the princes were independent landed magnates and opponents of centralization, it did imbue them with…influence at national level. Conscious of their high birth, the eminent princes laid claim to the role of the tsar’s closest counsellors. Such aristocratic pretensions on the part of the princely boyar elite could not fail to come into conflict with the autocratic aspirations of the first Russian tsar.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 124).

In other words, if Ivan was to become a true autocrat, he would have to cut his way free of the “spider’s web” of clans, whose power rested on their independent landholding.

The Russian historian Sergey Platonov, writing about Ivan the Terrible during the 1920’s,

“presented the oprichnina as a policy designed to weaken the old princely aristocracy by destroying its large hereditary landed estates and redistributing them on a conditional basis to the new class of small-scale military servitors.” Text continued after next image

Detail of my “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.’s” shows the lower levels of the noble clans.

During the oprichnina (and afterward, according to Pavlov and Perrie, p. 169-203), Ivan killed or exiled to far distant lands many of the mighty old hereditary landowners. In their former court positions and on their former estates, said Platonov, Ivan instead installed lower-born servitors who had the right to hold the land only as long as they were in service to the tsar (called “service tenure”). This destroyed the power base of the old hereditary landowners, removing their ability to limit the tsar’s autonomy.

Platonov’s view was generally accepted for decades, until, as so often happens, it fell out of favor when later historians raised questions about it.

For one thing, some historians* observed that many of the powerful old boyar and princely clans Ivan had exiled returned to court after the 7-year-long oprichnina (or according to Pavlov and Perrie, after Ivan IV’s death, p. 198), in their own turn ousting Ivan’s low-born courtiers. That sure made it seem that Ivan hadn’t intended to raise up those low-born courtiers after all. It seemed that life just returned to the pre-oprichnina status quo.

Janet Martin book cover

Other historians (e. g. Martin, p. 390 and Crummey p. 162-4) have argued that because Ivan was inconsistent in his choices of who to kill or exile and who to include in his oprichnina, he couldn’t have been pursuing a plan of social engineering. He exiled some princes and kept others at court, executed some of the low-born as well as some of the high.

“Over the course of the oprichnina’s existence, men of many backgrounds served in Ivan’s private army and court. Some came from aristocratic clans and many more from the lesser nobility. On occasion, some members of a prominent family served in the oprichnina, while others did not….

[Of those exiled to Kazan,] princes from the regions of Starodub, Iaroslavl and Rostov made up the largest single component…. [But] a significant number were not princes at all; a few came from distinguished non-titled families and considerably more from the lower echelons of the court.” (Crummey, p. 163-4)

Other historians have also stated that while the original oprichniki were of low birth, their composition later reverted back to the same old princes and boyars. (However, evidence for this point seems meager and appears to ignore Andrei Pavlov’s recent extensive research** on Ivan’s exiles/land transfers, including in the period after the oprichnina was formally over.)

Historians have also argued that a move by Ivan against the princes and boyars would have been purposeless, since all Russians, from the highest nobility to the lowest peasant, already agreed on the need for an autocratic tsar. No one, not even the princes, wanted a less centralized system.

Also, a semantic confusion seems to have crept into the debate. Some of the dissenting historians have considered that, by “raising up low-born courtiers,” Platonov adherents meant that Ivan’s new henchmen became a class aware of their own interests, with an independent power base from which to push for concessions from the tsar. These historians have accurately observed that in fact no new interest group or class arose. In fact, the Russian autocracy became stronger following Ivan’s reign, not weaker vis-a-vis the newly elevated servitors.

Also, a semantic confusion seems to have crept into the debate. Some of the dissenting historians have considered that, by “raising up low-born courtiers,” Platonov adherents meant that Ivan’s new henchmen became a class aware of their own interests, with an independent power base from which to push for concessions from the tsar. These historians have accurately observed that in fact no new interest group or class arose. In fact, the Russian autocracy became stronger following Ivan’s reign, not weaker vis-a-vis the newly elevated servitors.

“Both aristocrats (princes and boyars) and the service gentry accepted the unification of the land under the sole government of the Tsar, and the merging of service [land] tenure and allodial property…in which they all saw some advantages. Some Riurikid [the tsar’s lineage] princes who had survived in sufficiently strong clans might still hanker after their old appanage [independent land ownership] status, but the pervasive systems…acted as a barrier against any private initiatives,…and the monopoly of lucrative service drew the aristocracy and service gentry together” (Madariaga, p. 368)

* For example, Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980-1584 (2007), p. 392, and Madariaga Ivan the Terrible, pp. 182-3.

** Pavlov’s research articles unfortunately haven’t been translated from Russian, but they are described throughout Pavlov and Perrie book, Ivan the Terrible.

It’s important for all students to read the sources themselves to form their own opinions. But having gone over the sources recently myself in preparation for creating my new artwork about Ivan the Terrible (in my primary role as an artist), I feel energized to present my own conclusions.

Pavlov & Perrie book cover

I believe most points of contention about Ivan the Terrible for which real evidence exists can be integrated into a single picture of the oprichnina.

First, let’s look at some historians’ point that, since all Russians already believed they needed a single, all-powerful tsar, Ivan would have had no need to bludgeon them into that belief. Well, as Crummy said (above), even people convinced of the need for a dictator may still battle with each other over access and influence. And battle among themselves the Russian nobility certainly did.

One might draw an analogy to children who know in their heart of hearts they need their parents to reign supreme. Yet they squabble endlessly to one-up their siblings and get their way. Ivan the Terrible was like the dad trying to drive the car while the kids kicked and punched each other in the back seat. He finally turned around and smacked them. Or maybe I should say: tortured and beheaded some of them to cow the others into docility.

(Remember I’m not saying this is a good thing or that the Russian people got what was coming to them. I’m only saying that Ivan didn’t like the fighting and interference, so he clobbered people to stop it.)

Andrei Pavlov’s recent years of research in Russian archives have shown that criticisms of Platonov’s findings are on the one hand unfounded and on the other hand raise important nuances that need to be woven into our understanding of Ivan’s oprichnina.

To begin with, the monumental scale of evictions of magnates from their hereditary landholdings has now been confirmed by Pavlov’s research. “Over the entire period of the oprichnina,” he wrote, “the majority of Russian nobles may have been moved from their homelands…” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 142, my emphasis). Pavlov’s sources have also shown that removing many magnates from their huge estates enabled Ivan to reward his lower born minions with landholdings and money.

It is difficult to conceive of any other ruler in Europe having the power to force such massive migrations and land ownership transfers on his own population. Along with the terror Ivan visited on his people, this must have had a powerful impact on their way of life and their psyche.

Pavlov’s research confirms that, as asserted by recent anti-Platonov historians, many of the old princely and boyar families did return to the tsar’s court, some with promises they’d get their land back. However, Pavlov and Perrie found this return of the magnates did not occur until after Ivan IV’s death. They present evidence that even after the formal end of the oprichnina, Ivan continued the same oprichnina policies, relying ever more heavily on low-born henchmen (Pavlov and Perrie, pp. 169-200).

So does this mean that in the end the oprichnina had no effect, and therefore could have had no rational purpose?

Some historians’ vision that former magnates who survived the terror came back to court and went on with their lives just as before seems improbable. The returning magnates had lived through humiliation, impoverishment, torture, and terror. They may well have had a number of close family members and friends slaughtered, or have witnessed or certainly heard of Ivan’s ghoulish tortures and killings. Many former princes and courtiers were likely cowed into submission by this profoundly traumatic experience. As Chester Dunning wrote,

The resulting horror and dislocation traumatized the elite, seriously weakened many princely families, and increased the nobility’s dependence on the monarch (Russia’s First Civil War, p. 49).

In addition to the psychic impact, the princes and boyars had lost their power base: their hereditary estates. Pavlov and Perrie write that even in cases where magnates were told their land would be returned to them,

“it was very difficult in practice to implement this policy, which involved the large-scale expropriation of lands from their new oprichniki owners, and the allocation of other lands to the latter in their stead. In the context of the general devastation of the economy it was essentially unrealistic even to attempt this. As a consequence only a small proportion of the [displaced] nobles received their old estates back.” (p. 169)

The resettlement of the nobility “involved many problems and often led to their ruination and impoverishment…. [During the oprichnina,] land often passed repeatedly from one owner to another and fell into decline. Traditional farming methods were disrupted, and this had a dire effect on the peasants.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 143)

In short, while former magnates were allowed to return to high positions at court, many no longer owned the large, productive tracts of hereditary land which had been the source of their wealth and power before the oprichnina.

“Over the years of the oprichnina as a whole, the balance between hereditary and service lands, especially in the central regions of the country, shifted significantly in favour of service-tenure estates.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 143)

“The oprichnina badly damaged the family estates of the princely and boyar aristocracy, and it particularly harmed the hereditary landownership of the princes. The destruction of the boyars’ hereditary landholding and the loss of their previous links with the local nobility, led to a significant transformation of the Russian aristocracy, and made it completely dependent on the monarchy…. The sovereign’s court had previously had a territorial structure, with the most aristocratic and eminent nobles not only serving at court but at the same time heading their local associations of the nobility. By the beginning of the 1570s this had ceased to be the case, and the court had become organized on a new and more hierarchical basis. The privileged elite of the nobility, the Moscow ranks…had become detached from the great majority of nobles. They now…performed their service exclusively from the ‘Moscow list’ (based in the capital), which greatly increased their dependence on the state. This pattern of development of the sovereign’s court was to continue under Ivan Groznyi’s successors. As a result, the upper echelons of the nobility…were essentially turned into state officials, and as such they began to implement in the localities the harsh policies of the autocracy….” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 198-9).

Question 4:

Would it have been possible for Tsar Ivan to break up the landholding power-base of the old princes, boyars, and courtiers without using terror? Could he simply have peacefully decreed that the large hereditary estates were to be divided and distributed to a wider group of nobles?

I suspect Ivan mounted his terror precisely because he knew the magnates would never give up their large landholdings peacefully. But how could he find people willing and able to carry out years of executions, tortures, and evictions across the country? He did it by turning to the impoverished bottom of the noble class and offering them rewards they could never have won before the oprichnina.

“Service in the oprichnina opened up for low-born nobles new opportunities for a successful career and to enhance the social standing of their clan. Sometimes oprichniki of humble birth, in defiance of the traditions of precedence* received higher service posts than more eminent…boyars and nobles. The latter, fearing the tsar’s disfavor, did not dare openly defend the honour of their clan, and had to accept their loss….” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 113; see also p.187)

*Precedence was the all-important key to high posts in Russia, and the source of most of the battles among them for status and influence.

The newly-elevated low-born, “being completely dependent on state service, and obliged to the tsar for their career and material welfare, …provided Ivan IV with a loyal and reliable base of support for implementing his political plans.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 113-14).

But as a number of recent anti-Platonov historians have pointed out, Ivan didn’t want to raise up the low-born nobles as a new upper class, conscious of their common interests and eager to press their demands on the tsar. Quite the opposite. Ivan’s goal was to destroy the ability of all classes to limit his own will.

Historians such as Martin and Crummey accurately point out that Ivan was inconsistent in his rewards and punishments, sometimes exiling the lowborn and giving favors to princes. Crummey takes this inconsistency as one indication of Ivan’s insanity.

But I believe his point is answered by historians who have noted that the oprichnina strengthened the autocracy, not any one strata of the nobility. Ivan rewarded low-born nobles for a period of time in order to win their loyalty as his tools in his larger plan.

If Ivan wanted to assert his power over all levels of society, he couldn’t consistently reward any given category of people, or punish any other given category. His goal was not to create a new powerful class of favorites, but to undermine the security of all of them.

So Ivan had to be somewhat capricious. Only in this way could he make clear to every class of people that they had no independent safety outside his good will.

Question 5:

After reading some of the sources what is your own picture of Ivan the Terrible and the oprichnina? If you’d like to challenge any part of my reasoning – or if you’d like to agree – I’d love to hear from you in a comment or via email.

You may have noticed that this entire discussion has been about different levels of nobility, not about those most subservient of all, the soon-to-be enserfed peasants. And of course, they were the real losers in all this. We’ll take up their lives more in later Study Guides.

Why, in my painting of Ivan the Terrible above, is he riding on a broom with a severed dog’s head on its front? Why did the real Ivan choose these symbols?

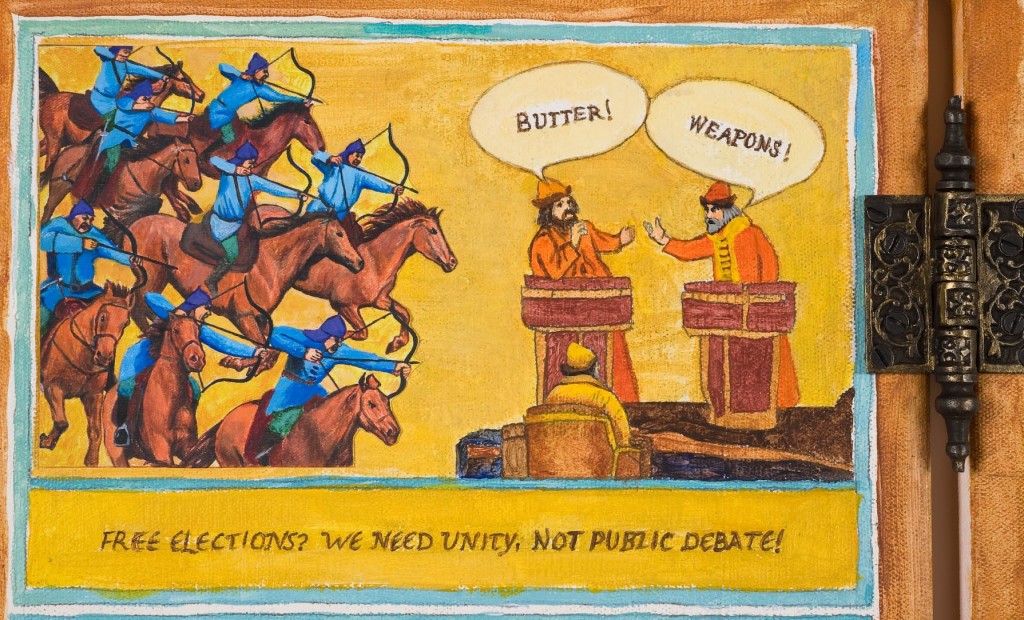

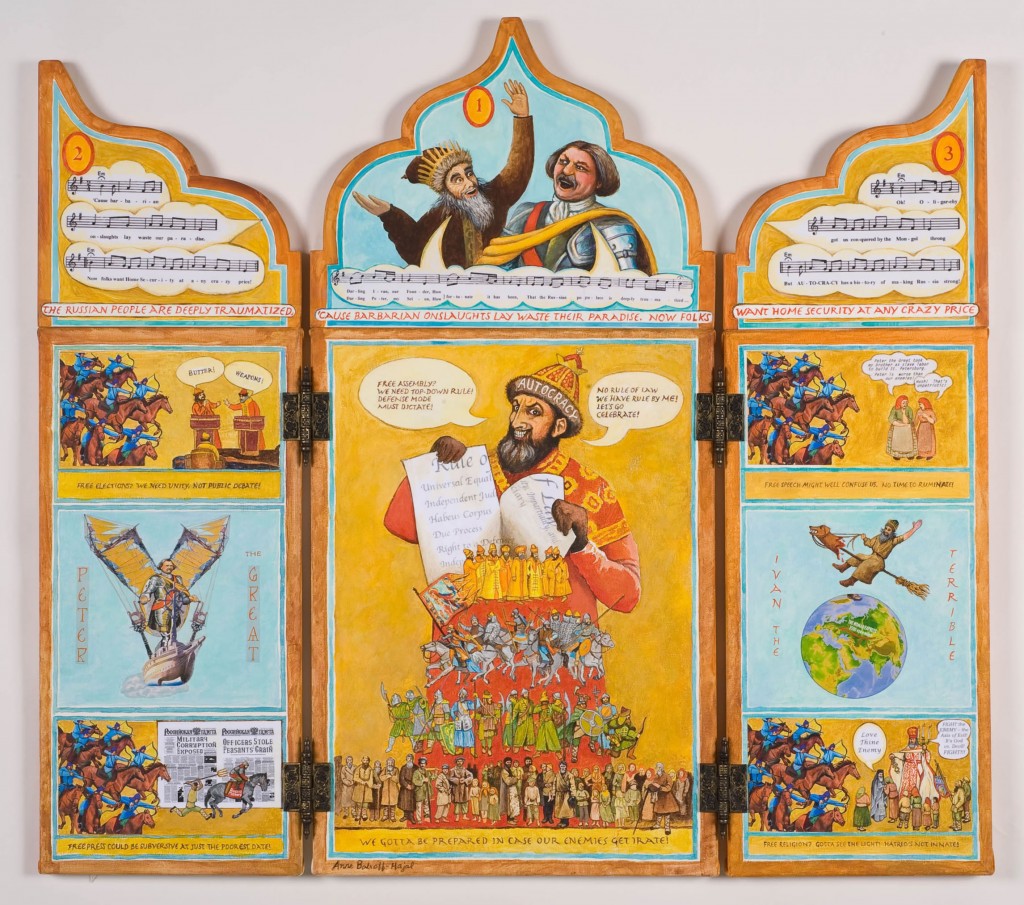

Two PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS main characters, Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, sing about the glories of autocracy. Detail from "Home Security At Any Crazy Price"

This is the second in a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. (The first, Introductory Study Guide is here).

In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

_____

A. Was Russia forced to expand to take over the southern steppes all the way to the Black Sea in order to protect its people from constant Tatar invasion and slave raiding?

"Home Security At Any Crazy Price," by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 36" x 40" . 2009

B. Or was Russia greedily expansionist, grabbing up territory it wanted rather than needed to protect its people? Could Russia have built a single strong defensive “Great Wall of Russia” effectively enough to block all Tatar incursions, rather than multiple “Great Walls” ever farther south?

C. Might the Tatars have had other choices than slave-trading and raiding to support themselves? Why were slaves so widely used at that time, including by the Ottoman Empire?

D. Are the Tatars and Ottomans the bad guys in this saga, and the Russians the good? Is reality more complex than that, or is this a clear cut case of good vs. evil?

You won’t be able to answer these questions now. But think of them as mysteries and yourselves as detectives. As you learn more, look for clues that may help you form your own opinions.

If you want to understand Russia, you need to be able to picture its massive expenditure of resources and human lives – for nearly its first five centuries – to protect against invasions and slave raids across its southern steppe frontier. Russia contains the largest expanse of flat land on earth. There was very little natural protection on the vast plains between Russia and the Black Sea. In the southern grasslands, there weren’t even forests to hinder invaders. Russia therefore had to create a man-made defensive system to protect its immense open frontier. (Continued below image)

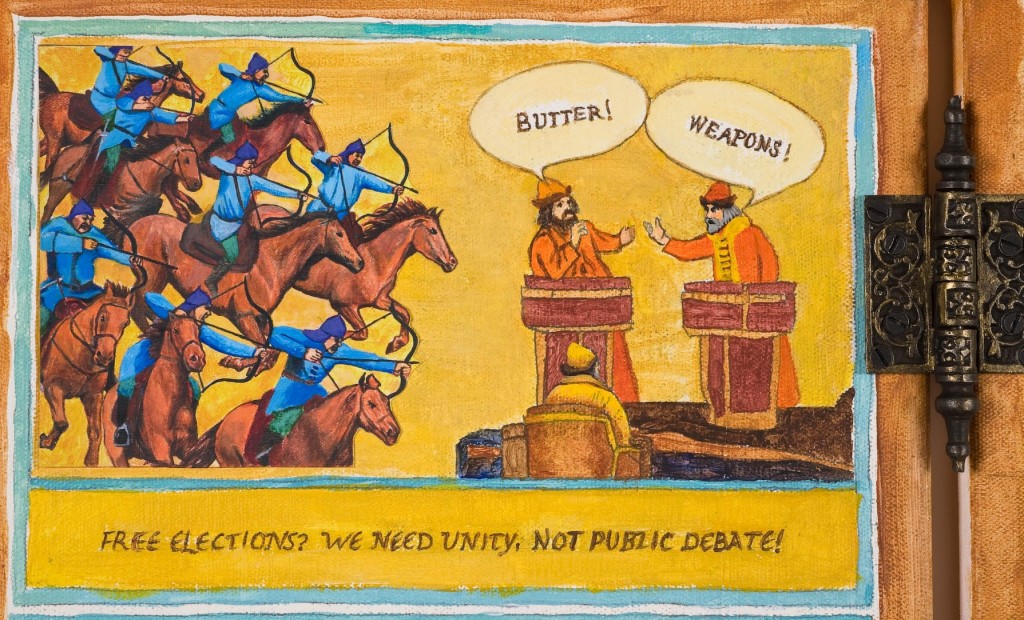

Detail of left panel, "Home Security At Any Crazy Price," by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 36" x 40" . 2009

When we envision Russia’s military history, we often think of its wars with European and Baltic nations to its west or of Russia’s rapid expansion across Siberia.

But at least as important in shaping Russia’s government and society was its southern frontier. This frontier was perhaps unique in all the world in its vast size, combined with its nomadic Tatar inhabitants who lived largely by raiding and slaving, partly to supply the powerful Ottoman Empire next door to them.

Americans and other Westerners may tend to focus on Russia’s eastern and western wars because we identify with them. European neighbors were Western, like ourselves. And Russia’s expansion across Siberia mirrors US pioneering expansion across our own western frontier. In short, we have points of reference in our own experience for Russia’s battles with populations to its east and west. (Continued below image)

But for the US, there is no parallel to Russia’s southern border. Over half our southern limit is formed by water: the Gulfs of Mexico and California. The single country bordering our south, Mexico, was far less powerful than the Ottoman Empire and its client Tatar khanates.

So we have no point of reference for Russia’s south. It’s not easy for us to wrap our heads around the implications of the largest expanse of land on earth without natural barriers to prevent constant incursion and annual “harvesting of the steppe,” the abducting of hundreds of thousands of Slavs sold into slavery in the powerful neighboring empire (Ottoman).

Let’s try to give ourselves some points of reference to help us picture Russia’s centuries-long struggle to make its southern population safe along this vast open frontier.

Brian L. Davies book cover

Most towns in southern Russia were originally founded by Moscow as garrisons designed to protect against invasions and raids. Towns couldn’t rise on the steppe organically, based on trade or agriculture, because a settled conglomeration of people would be an immediate target for Tatar raiders. Towns could exist only if the central government built a garrison, with troops to protect it and patrol the surrounding wide open plains. For example, in 1677-8, “the southern regions mustered the largest number of town servicemen ever, nearly 47,000 in seventy-three cities.” (Stevens, p. 127).

As early as the 15th century , the Russian government began constructing a series of what have been called “the Great Walls of Russia,” each several hundred miles farther south in the steppe. These lines were a combination of fortified towns, stockades, earthen ramparts, trenches, guard posts, and mobile patrols.

Brian L. Davies describes a section of the Belgorod Line, a 25 km earthen wall built by 950 laborers in 5 months:

This wall stood nearly 4 meters high and had seventy bartizans [overhanging turrets], four earthen forts, breastworks, and ditch and anti-cavalry fences.

There were very few peasants living and farming on the southern plains because they would have been too vulnerable to raiders. (Continued below image)

So to create a population to guard Russia’s defensive lines, Moscow sent recruits to the frontier, providing them with plots of land near garrisons to farm for their own livelihood and for taxes. Carol Belkin Stevens (Kira Stevens) has done brilliant research into the lives of these people for her Soldiers on the Steppe: Army Reform and Social Change in Early Modern Russia. If you’re writing a term paper on this subject, her book is a must.

Garrison servicemen were responsible both for guarding their forts and for patrolling the long defensive lines snaking out from their towns. Constant vigilance was needed to spot fast-moving, skilled Tatar raiders moving across the steppe. For example, writes Stevens, in the town of Valuiki,

Seventy mounted steppe patrolmen left the fortress at six-day intervals from late spring through early fall. Their tour of the steppe was extensive…watching for signs of Tatar approach…. Mounted servicemen patrolled between outlying towers or small fortresses and into the distant districts. Cavalrymen in shifts of six relayed any messages or goods locally; sometimes they provided escort and protection to officially sanctioned groups traveling toward the lower Don. Beyond the frontier they also stood guard over work on distant and exposed fields or carried news of imminent attack to outlying villages…. Closer to Valuiki, fifty mounted [troops] patrolled the towers of the fortress….

Warnings of imminent Tatar attack led to general alerts, and town walls were manned more densely – often by garrison servitors from other towns. Musketeers and hereditary servicemen escorted criers with news, orders, and calls to arms around the province. (Stevens, p. 131-2) (Continued below image)

In addition, these servicemen repaired old and built new fortification lines. For example, the southern-most Izium line was constructed by 30,000 men over several years. “Anticipated Tatar attacks during the construction of the Izium wall placed nearby garrisons on alert, even while town servicemen from further north were actively engaged in building.” (Stevens, p. 133-4).

Provisioning Garrisons and Campaign Armies over Vast Distances

Carol Belkin Stevens book cover

In addition to supporting themselves on their own farm plots, southern servicemen were required to contribute grain for the support of campaign forces and people constructing new defenses farther south. They were responsible for carting this grain themselves to central storage depots, which could be a hundred miles or more away. Servicemen had to build granaries, warehouses, and river boats to move grain southward; they also worked on the docks. “Because old boats could not easily be returned upriver, the gathering of labor, materials, iron parts, and the selection of loaders, escorts, and rowers were annual events (Stevens, p. 134-5).

In the context of continual danger from the south, only a powerful central government could mobilize such massive efforts, and squeeze such great resources and labor from its people.

Stevens gives an amazing description of the first attempt to move campaign troops across the entire steppe to try to do battle with the Crimean Khanate on its own stronghold:

…the army and its supplies were a nearly unmanageable mass…. The massive army led by Prince Golitsyn proceeded slowly across the steppe. It was organized with an advance guard of ten regiments, followed by a long rectangle made up of an estimated one hundred regiments and the supply train. In that long rectangle, the main infantry forces surrounded a moving barricade of 14,000 horse-drawn carts that were arranged in ten rows and flanked on the sides by 6,000 more carts in seventeen parallel rows. The front and flanks of this oblong – 2.3 miles across and 1.2 miles long – were protected by cavalry, with the artillery bringing up the rear.

[At best] the army would have needed more than two and one-half months of any summer campaign to reach…the Crimea and return. In addition, any such venture required the availability of at least some food, water, and wood along the route….

By 1687 Muscovy could, by exerting extraordinary organizational effort, successfully gather more than enough food for that part of the 112,000 man army it chose to supply. Russian campaigns against the Crimea, however, posed unusual problems in the disbursement of supply to a large army. Elsewhere in Europe, similar disbursement problems would be resolved partly by reliance on local agriculture and partly by a series of provision magazines, at regular and quite short intervals…. Neither option was available for the Muscovites proceeding across scantly populated and hostile steppes against Crimea. (Stevens, p. 119-20; my emphasis)

In fact, Golitsyn’s army was never able to reach the Crimea. “The Tatars had burned the grass of the open steppe; to cross that territory, the army would have had to invest enormous effort searching for fodder for its more than 100,000 horses.” They had to turn back homeward without ever seriously engaging the enemy.

It would take almost another century before the Crimea was conquered, by Catherine the Great.

Brian L. Davies and Kira Stevens have done all-important research on Russia’s extraordinary southern struggles, each from a different perspective of the Russian side. The terrific work of Michael Khodarkovsky, published in Russia’s Steppe Frontier, The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500-1800 (in an Indiana-Michigan series, one of whose two general editors was my UM advisor, William G. Rosenberg), in addition gives more of a sense of the Tatars the Russians battled against.

This trio of books is essential reading for anyone studying Russia’s south. In fact, given the importance of the south to all of Russian history and the shaping of its society even today, these books are important for anyone studying Russia period.

My PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS artwork plays whimsically with the serious saga of the impact of Russia’s peculiar defensive dilemma on its government and society. I believe that Russia’s autocratic government arose in response to the military struggles described in the work of Davies, Stevens, and Khodarkovsky. Russian society was organized as a military chain of command, with no independently-organized power bases. For five centuries, the entire country was ever-prepared to fight against the raids and invasion which came multiple times virtually every year. And Russia’s rulers took full advantage of its people’s desperation, building what Ronald Wright called a protection racket.

For more on PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS, please see the article recently published by Terrain.org, A Journal of the Built and Natural Environment, as well as other posts here. A PLAYGROUND triptych, “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” was described by the New York Times as “an homage to Joseph Cornell…full of wonderful goodies.”

This is the first in a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

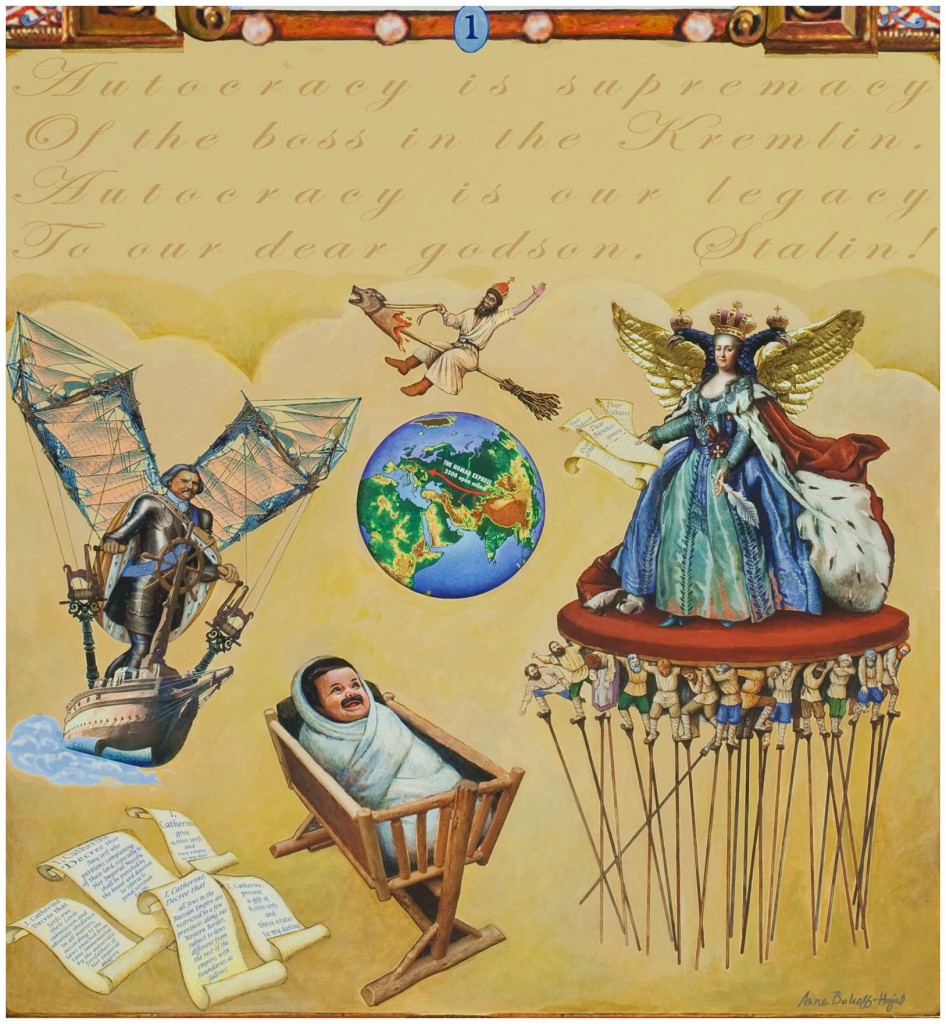

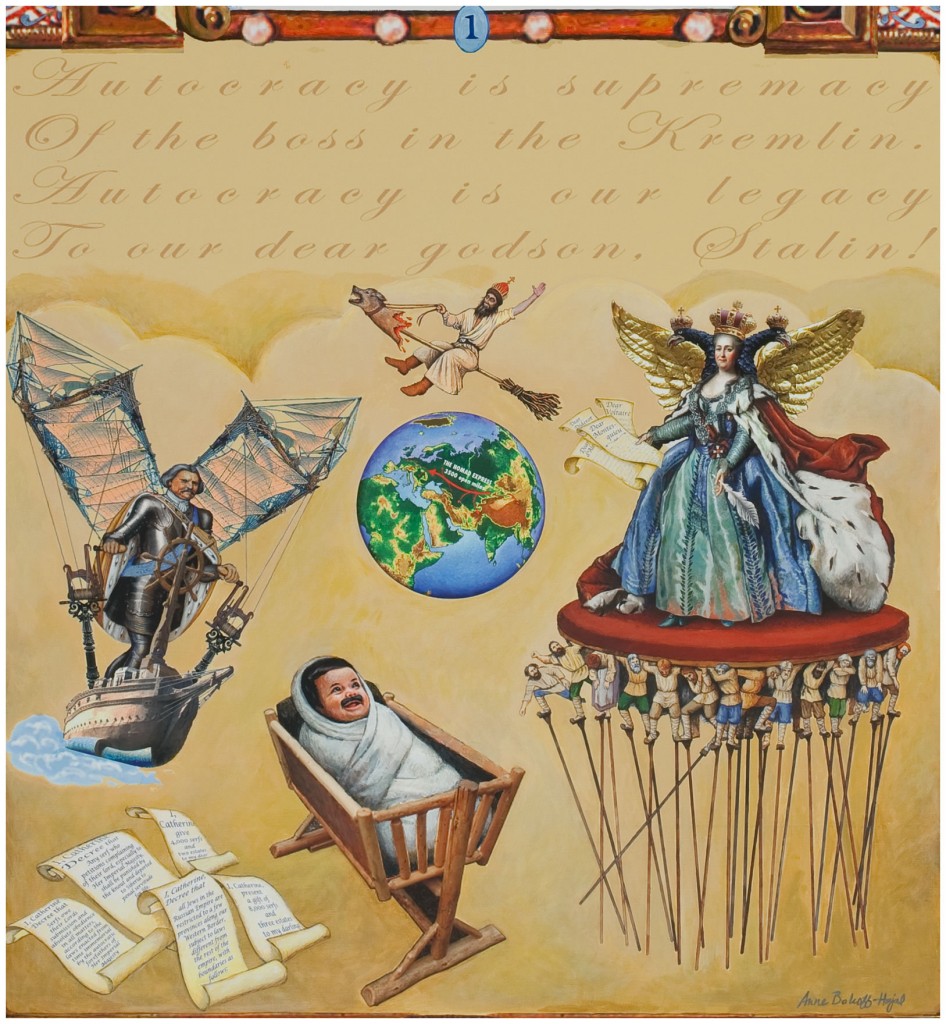

My Playground of the Autocrats art animates a framework for studying Russian history. This framework explores how Russia’s present-day society and government are embedded its past, from the 13th century through the rise of Muscovy, Tsarism, Communism and post-Communism. In the image below, the Tsarist godparents of a mustached infant Stalin bestow the blessings of their autocratic past on him, to his delight.

Stalin’s tsarist “godparents” bestow the “blessing” of Russia’s past on Soviet Communism. Detail of central panel from “Dress It Up In Resplendent Clothes” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

In these Study Guides, I’ll suggest “big questions” for discussion. I’ll take a long perspective, not focusing on fine details: less on trees and more on forest. Actually, I’ll take another giant step back from the forest to see it in wider perspective, to ask what forest conditions cause certain trees to grow there but not others, one forest ecosystem to develop instead of another:

What caused an autocratic state to grow on the vast territory that became Russia, rather than another form of government? Was it pure chance, or were there particular conditions that engendered it?

From Chester Dunning and Norman S. Smith, “Moving Beyond Absolutism: Was Early Modern Russia a ‘Fiscal-Military’ State?” Russian History, 33, No. 1 (Spring 2006) pp. 38-40 (my bold):

“The origins of Russian autocracy are complex and controversial… [They] resulted in the rapid development of a service state…in which he performance of duties that directly or indirectly bolstered the country’s security were required from virtually everyone. As a result, Russia’s tsarist system became ‘one of the most compulsory in Europe….’

“Coming into the sixteenth century, Russia was, more than any other contemporary society, ‘organized for warfare.’ During the sixteenth century Russian military forces fought almost constantly, and Russia actually emerged as a major military power before the reign of Ivan the Terrible (1547-84), the founder of the Russian empire. The sixteenth century also witnessed the rapid development of a powerful Russian central state administration…. As in other fiscal-military states, that led to extremely coercive efforts to harness Russian society to the task of paying for the prohibitively expensive costs of early modern warfare. The extraction of domestic resources was greatly facilitated by the fact that nowhere else in Europe was the principle of service to the state pressed as far as in Russia….

“Generously rewarded for life-long service, the tsar’s bureaucrats were incredibly loyal and hardworking, and they succeeded admirably at imposing the central state’s authority.

“From the very beginning, Russia’s bureaucrats were primarly oriented to the task of raising, financing, and supplying the tsar’s military forces. They were not hampered by the concerns of bankers or merchants and were therefore basically free to extract resources from the economy with no concern for or understanding of the impact of their actions. Taxes were imposed with zeal to pay for the cost of war…. Over the course of the [16th] century taxes for many Russians rose 600 percent….”

Why was the 15th and 16th century Russian state so continually focused on war, devoting more of its resources to military mobilization than did any other society? Research over the last decade or so indicates that Russia’s vast open southern steppe frontier forced the country to mobilize militarily from top to bottom. Virtually every year, semi-nomadic Tatar raiders, in small groups and large, galloped across the wide open plain to plunder and “harvest the steppe” of humans to sell into slavery in Crimean slave markets. Over several centuries, hundreds of thousands of Russians were abducted and marched in chains across the steppes to be sold into bondage. No population except Africans has been enslaved more than the Slavs.

Some of the historians who have researched Russia’s southern steppe frontier are Carol Belkin Stevens, Michael Khodarkovsky, and Brian L. Davies, who wrote in his Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500-1700 (pp.1, 17, 23):

“For nearly four centuries – from the reign of Moscow Grand Prince Vasilii III through the reign of Russian Empress Catherine the Great – the Russian government, army, and people confronted the threats of Crimean Tatar invasion and raiding on their southern frontier….

“There were forty-three major Crimean and Nogai attacks on Muscovite territory just in the first half of the sixteenth century…. Large Tatar forces were able to penetrate into the heartland of Muscovy even in years when…the Russians [were able] to increase regimental strengths along their southern frontier. In 1571 Khan Devlet Girei invaded with an army of 40,000 Crimeans, Nogais, and Circassians and burned much of Moscow, allegedly killing 80,ooo and carrying off 150,000 captives. The Tatars burned the suburbs of Moscow again in 1592 while the bulk of Russian forces were busy fighting the Swedes on the northwester frontier. In 1633, while the tsar’s army was preoccupied in a western campaign…the Crimeans and Nogais launched devastating attacks upon the interior districts of Kashir and Serpukhov….

“[S]laveraiding was essential to the economy of the Crimean Khanate. And if Tatar slaveraiding was a lower-intensity threat than invasion, it was also a nearly constant threat and inflicted heavy costs…. Tatar slavers raided the southernmost Muscovite colonies almost every summer, capturing servicemen and peasants working in their fields, driving off herds of livestock, burning villages and town suburbs, and ambushing patrols and merchant caravans. Most of these raids were undertaken by chambuly of a few hundred men yet were able to do a great deal of damage.”

Richard Hellie book cover

Every member of the Russian gentry was obligated to mobilize for half of every summer along the frontier to defend against raids. This put huge a burden on gentry members who also had to maintain agriculture on what were often small estates. Wrote Richard Hellie in Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy (p. 29),

…it was not a standing army. Usually one half was called up in the spring, to await an expected Tatar invasion on the frontier, and served to mid-summer. Then it was replaced by the other half, which served until late autumn. During either offensive or defensive emergencies, which were frequent throughout this period, both ‘halves’ were summoned simultaneously…. The success of any mobilization call was highly dependent on the condition of agriculture at the moment of the summons. If a serviceman’s lands could not provide the wherewithal for his service, he would not report for duty.

To the extent possible given the immense drain on resources, all of Russian society was organized like an army ready for war. The Tsar was commander in chief. Independent organizations and institutions were not allowed, just as in armies the chain of command from must always to be obeyed. While Tsar and elites benefited most from this system, the general populace acquiesced in order to be protected against constant threat from across Russia’s great flatland.

A. Are there factors beyond human decisions that shape the development of societies in general and in particular Russia?

B. Or are human beings and their free choices the primary drivers of history, including in Russia?

C. Can you think of a different position altogether, or some combination of A and B?

A. Once an autocratic “garrison state” was formed in Russia, could it have been eradicated in later periods when the country was less vulnerable to outside attack?

B. Or were elites able to maintain themselves in power even after the “garrison state” was no longer as necessary?

In other words, is my triptych godparent image accurate or not? Is the past the godparent to the future, no matter how revolutionary that future seems superficially?

These are very big questions that you won’t be able to fully answer at the beginning of your Russian history study. As you read and hear more about Russia, you’ll gather more evidence to form your own opinions about them.

On the similarities between the trade in Slav and African slaves: Britannica.com.

Robert O. Crummey, The Formation of Muscovy, 1304-1613

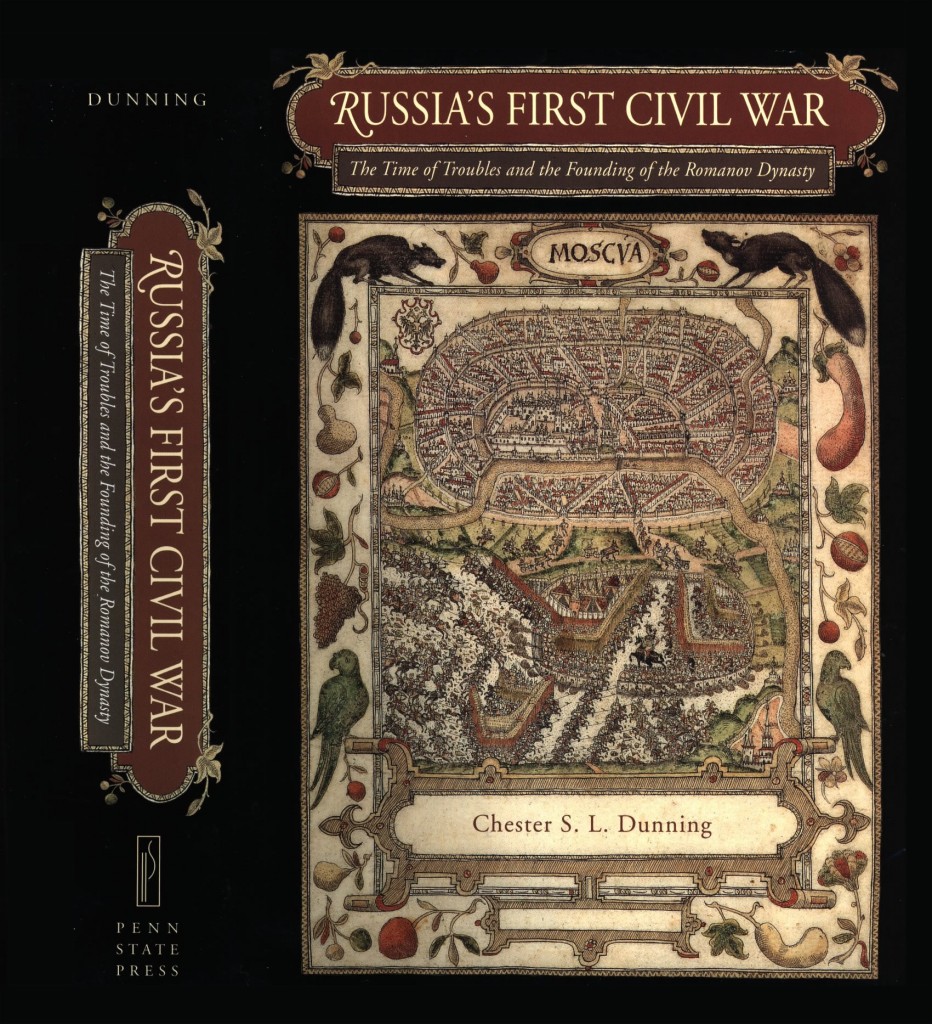

Chester Dunning, Russia’s First Civil War: The Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dynasty.

The beautiful cover of Chester Dunning’s book RUSSIA’S FIRST CIVIL WAR, THE TIME OF TROUBLES AND THE FOUNDING OF THE ROMANOV DYNASTY, published by Penn State University Press, 2001, shows “The Rebel Siege of Moscow, 1606”

“Home Security At Any Crazy Price”

Long before 9/11, I had written early drafts of lyrics for what would become one of my mixed media artworks about Russia, Home Security at Any Crazy Price.

At the time I thought my theme was very specific to Russian history, a bit too esoteric for most Americans. It was about Tsars building their dictatorship by taking advantage of popular fears from centuries of brutal enemy onslaughts. I planned to paint Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great singing to each other:

Darling Ivan, our Founder (Darling Peter, my Scion),

How fortunate it has been

That the Russian populace is deeply traumatized

‘Cause barbarian onslaughts lay waste their paradise.

Now folks want home security at any crazy price. (Continued below image)

“Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . 36″ x 40″ . Acrylic and digital images on canvas and board . 2009

Then came 9/11. Many Americans’ response – their sudden willingness to give up personal freedoms if the government could only keep them safe – revealed that a similar dynamic to Russia’s can play out wherever people come under attack and feel profoundly threatened.

All at once, my planned artwork seemed absolutely current and relevant to the US today. Continued below image

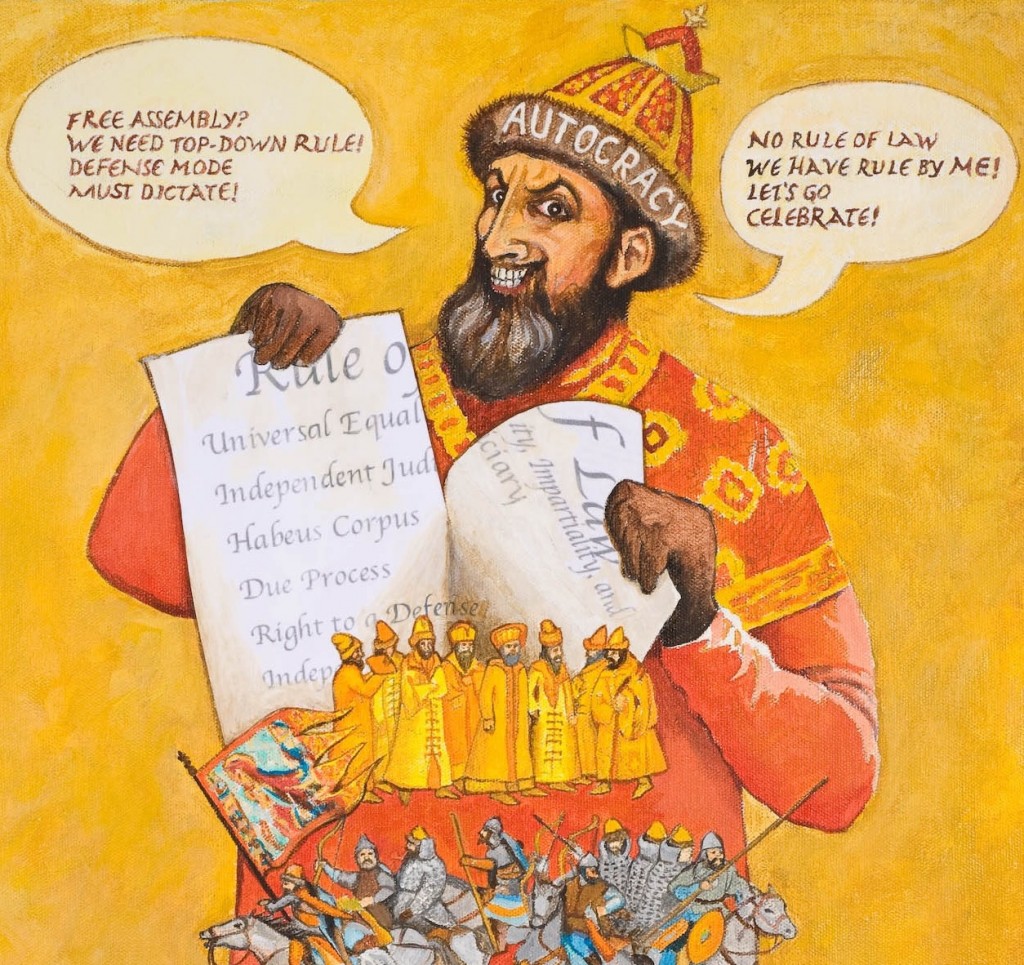

Detail of center panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Americans have relaxed a bit since 2001, having experienced no further attacks on the scale of 9/11. We’re no longer as ready to trade our civil liberties for a strong government to protect us from seemingly imminent terror.

Detail of right panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Haja

But what if the US had had repeated assaults every year since 2001, in which thousands of Americans were killed? And if yearly onslaughts continued indefinitely?

What if we lived in a land so vulnerable that we had a 9/11 every year for over five centuries?

Then what kind of government would we be willing to tolerate? One that abridged our personal freedoms constantly in order to keep us ever-mobilized and battle-ready? Would we accept our entire society being organized like a military hierarchy, with a single tsar at the top commanding us into position to survive our unending state of emergency?

Few Americans are aware that Russia was born and forged in terror from outside its borders: constant devastation by enemies and the kidnapping into slavery of hundreds of thousands of Russians, from the 13th century till the 18th.

Detail: Right upper panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

First, ferocious, brilliantly-skilled Mongol raiders pillaged, sacked, brutalized, and occupied Russia for a couple of hundred years. For centuries after that, the Mongols’ descendants, the Tatars, swept across Russia virtually every summer, abducting 5,000, 10,000, 20,000 or more people each year to sell in the Black Sea slave market, a straight shot across the steppes to the south.

In fact, our word “slave” derives from “Slav.” No population in the world other than Africans have been enslaved more than Slavs. (For more on the reasons, see “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth.”)

In short, Muscovites were traumatized by terror, as were New Yorkers on 9/11. But Russians were terrorized again and again for hundreds of years.

Every country in history has been repeatedly attacked. Their people too have had to drop normal life to run inside inside the walls of their local castle for protection.

What was different about Russia was the frequency of assaults. Slave raids occurred not once in 10 or 25 years – but every year. Because these raids occurred every year, they earned the moniker “the harvesting of the steppe.” Every member of the Russian gentry was responsible for military duty at the frontier for one half of every single summer to protect the vast southern border against raids.

Detail of center panel from “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

The frequency of attacks on Russia was partly due to its lack of natural protective barriers along a longer open border with powerful enemies than anywhere else on earth.

The only geographic area comparable with Russia’s southern frontier might be the American Great Plains frontier (north/south orientation) in early US history. But next to the US frontier lay the remnants of native tribes nearly wiped out by disease spread from Europe to the New World. Next to the Russian frontier, in contrast, were large, flourishing, major powers of the day: the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire.

It would be as if the early United States had had the equivalent of both El Qaeda and Akhmedinezhad’s government living along its frontier.

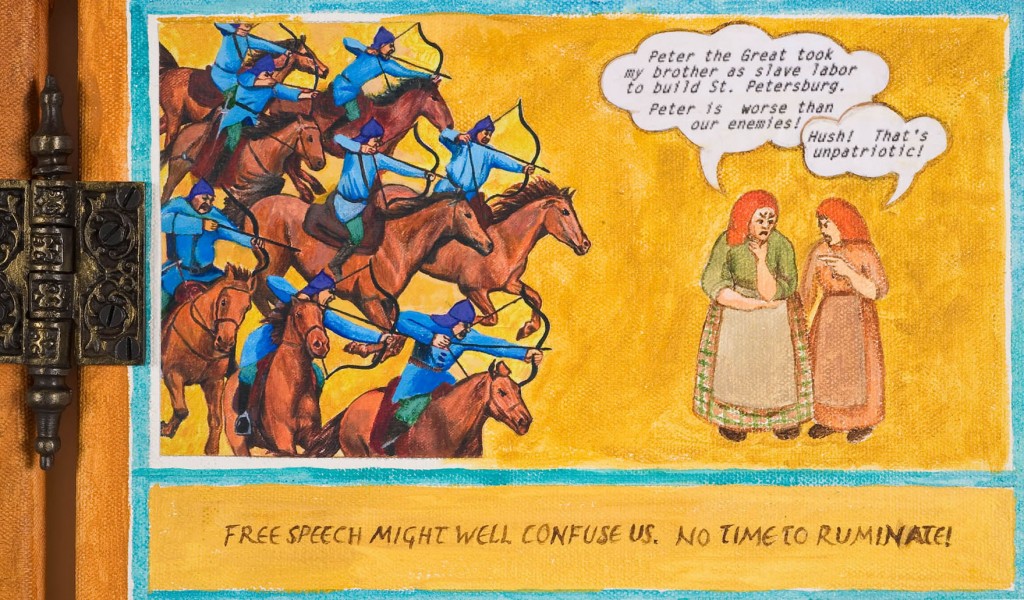

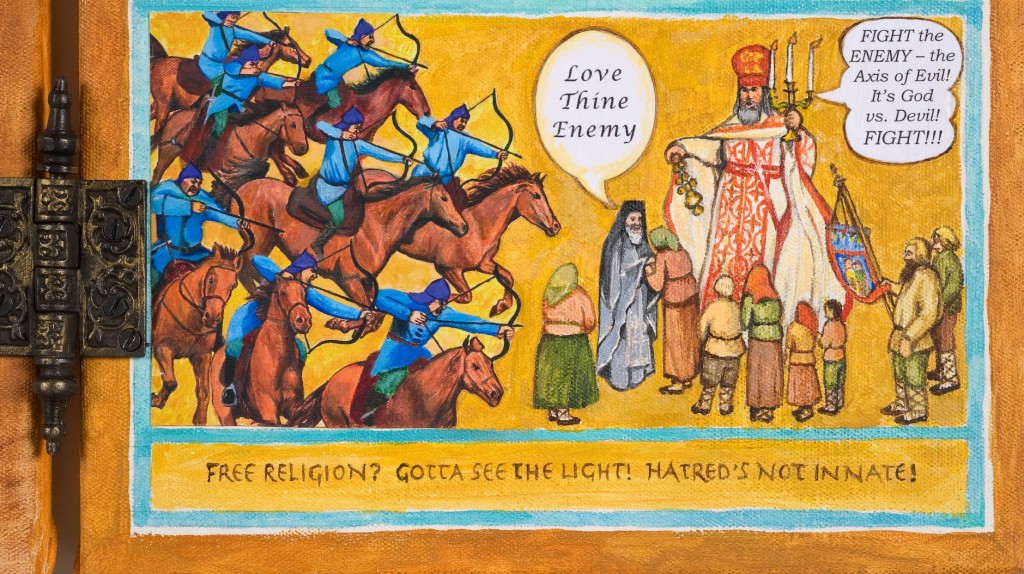

The tsarist state was military hierarchy writ large (above). The entire society could never relax from war preparations and fighting. Centers of power independent of the tsar couldn’t develop because the military chain of command always had to be in effect society-wide.

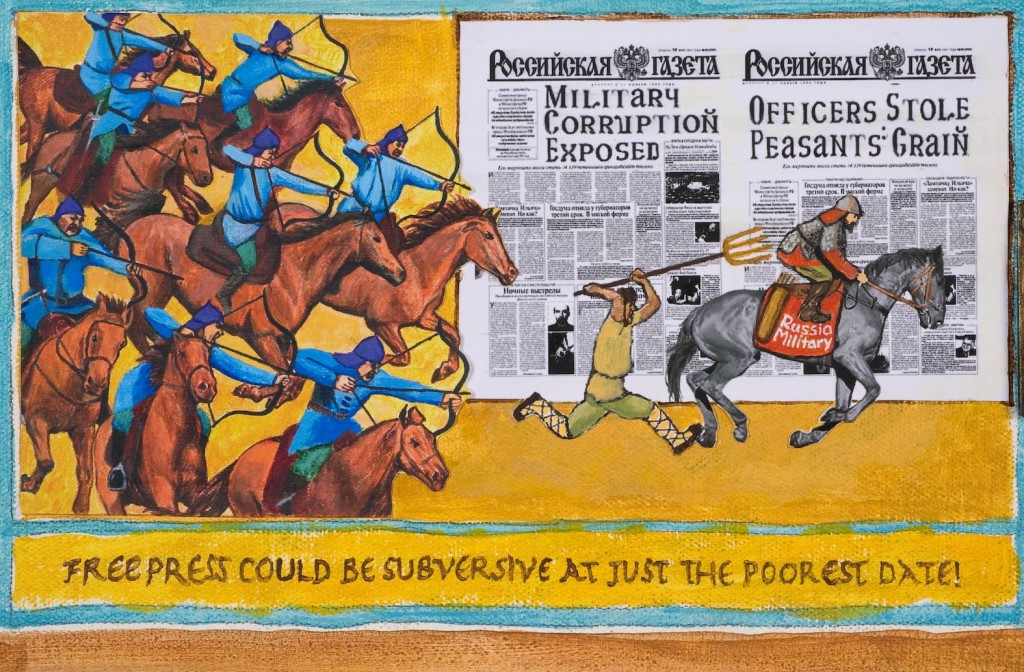

Home Security At Any Crazy Price visualizes the impact on civil liberties of the unending threat of attack. Continued below image

Detail of lower left panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Institutions which have been forged over a period of five centuries don’t change overnight. New autocrats make use of earlier institutions – controlled press, secret police, patronage – to maintain and strengthen their power.

Detail of right panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Since the fall of Communism, Russia is again becoming more centralized. Putin has asserted control over the media. No non-Kremlin newspaper can garner significant circulation. Journalists who report stories the government doesn’t like are murdered. Real opposition political parties aren’t allowed to run candidates.

Will Russia ever become a fully pluralistic society? I don’t know, but I’m interested in watching to see. Continued below image

Detail of lower right panel, “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal.

The US experience of terrorism on 9/11 can help us better grasp why Russia developed an autocratic state. A nation of people who experienced almost yearly trauma for centuries adapted to their society’s being permanently organized like a military chain of command with no insubordination from the ranks.

We can also learn from Russia’s experience the terrible consequences of sacrificing civil liberties for security over the long term. Russian history can serve as a cautionary tale for what could happen to us if we’re too ready to trade personal freedoms for powerful government. ■

Below image are links to more posts about PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS triptychs.

Detail: Top center panel of “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

An introduction to the PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS series is here. Other posts about these triptychs are:

Portraying the Vast Flatland of the Playground

The Most Exposed Terrain On Earth

Designing the Character of Peter the Great

Catherine the Great: A Satirical Visualization of Russian History and Society

What is Catherine the Great Singing in Her Triptych?

How I Painted and Composited Catherine the Great (and Stalin)

How does an artist portray a grand sweep of centuries?

Detail of center panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Russian history is full of high drama. Mongol raiders thundering across the endless steppes toward small Muscovite towns. Human terror and suffering. Tsarist defenses and brilliance, ambition and intrigue. Russian culture’s astonishing splendor and beauty.

It all makes a perfect subject for art.

But how can a painter visualize a grand sweep of centuries? What recipe can be cooked up to entertainingly portray a millenium of Russian history?

That’s the challenge I set for myself in my series of triptychs collectively entitled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS. The first in the series is The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth.

A detail of my “recipe” to convey this triptych’s story is to the right. I use satire, color, action – and song lyrics (see images below).

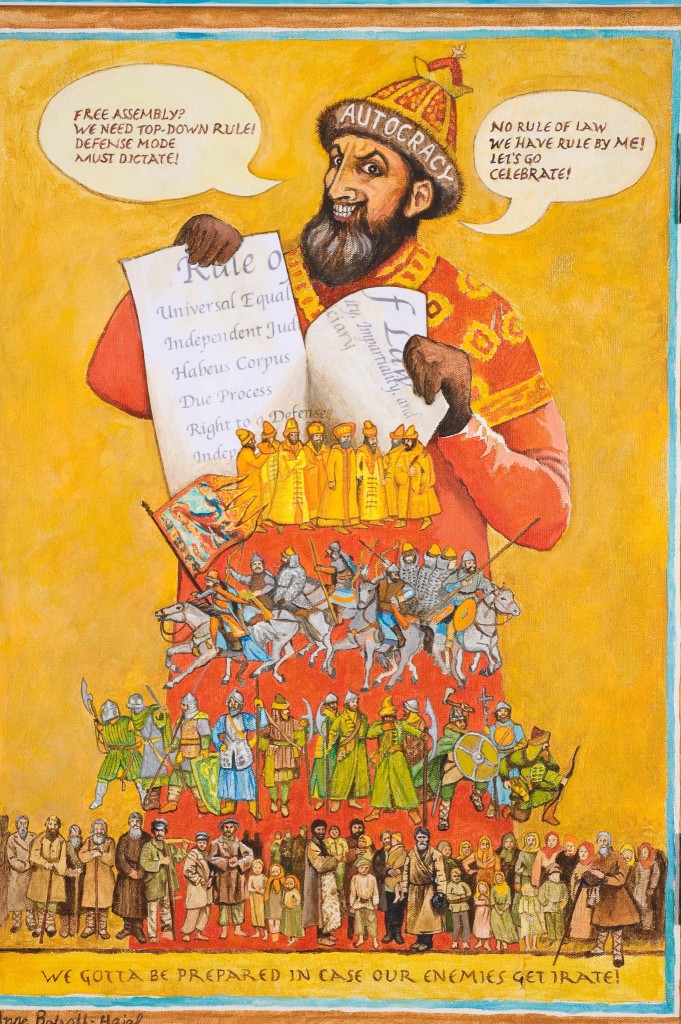

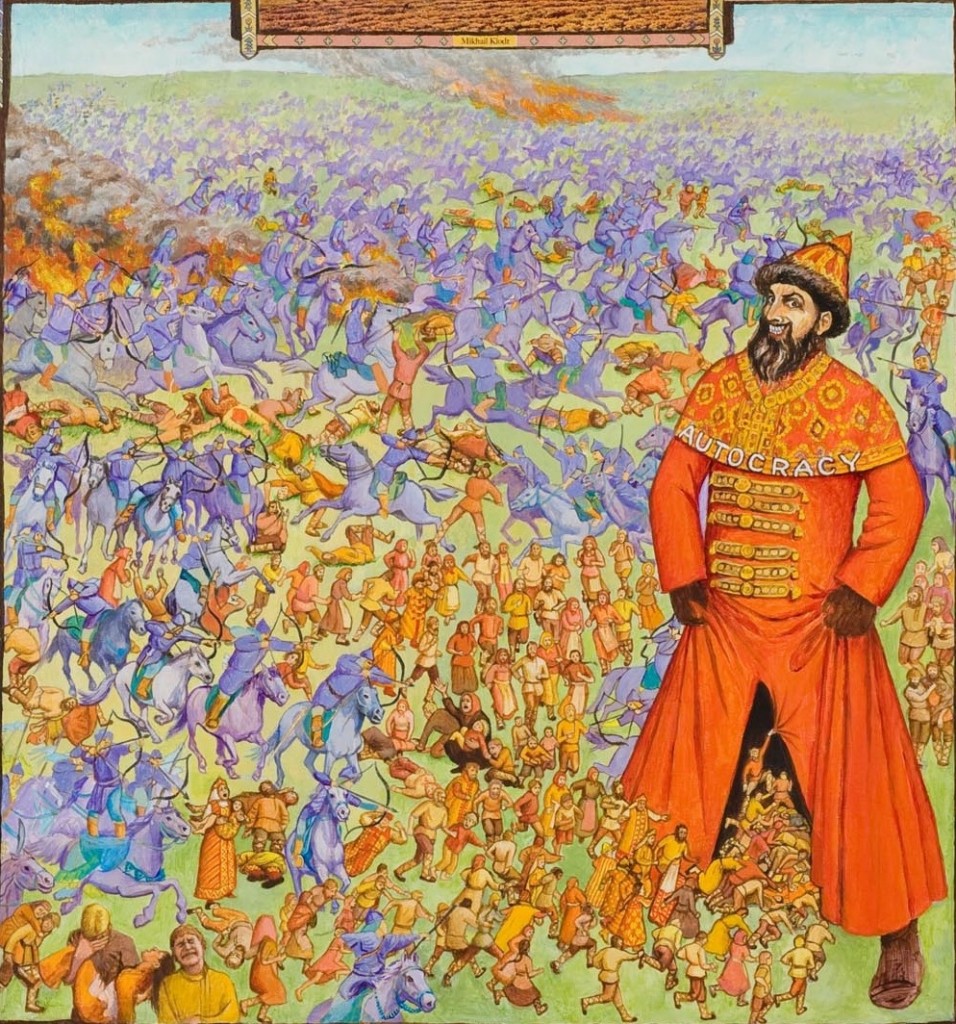

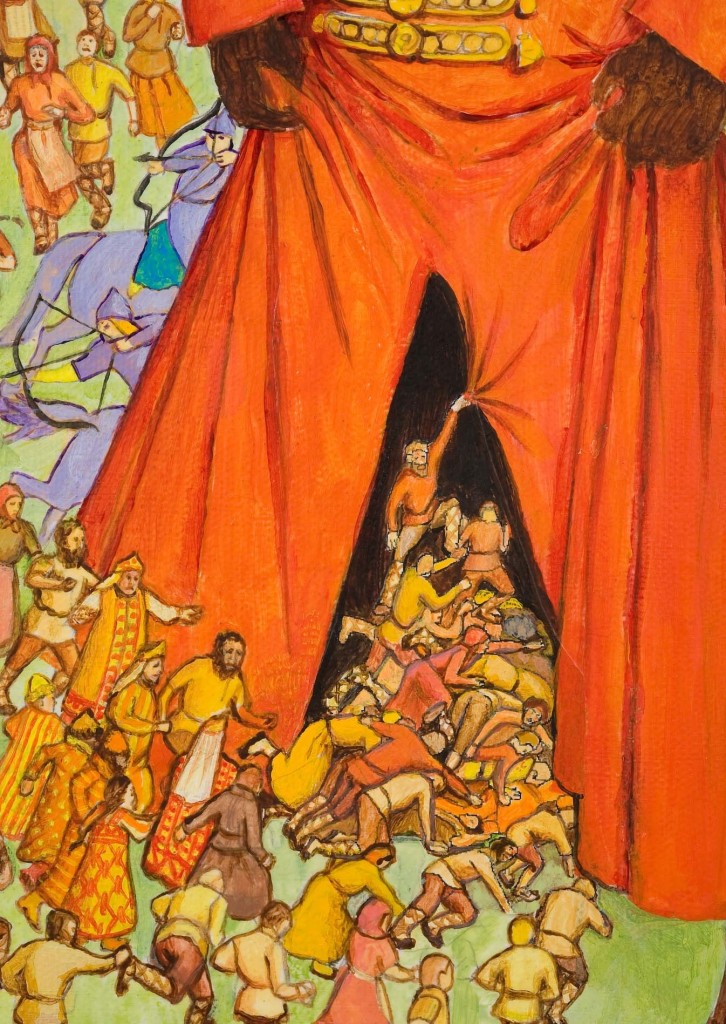

But my most important ingredient for each triptych is visualization of a historical process. The centerpiece of my visualization of The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth is a tsar-type figure (above) lifting his skirts to gather in lots of Russians underneath.

Hmm, the viewer might ask. Who is this guy labeled “AUTOCRACY,” and why is he grinning with malevolent glee? And what’s going on with all those frantic people running to hide inside his robe?

Just what historical process am I visualizing here?

“The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth” . 24″ x 48″ . Acrylic and digital images on canvas

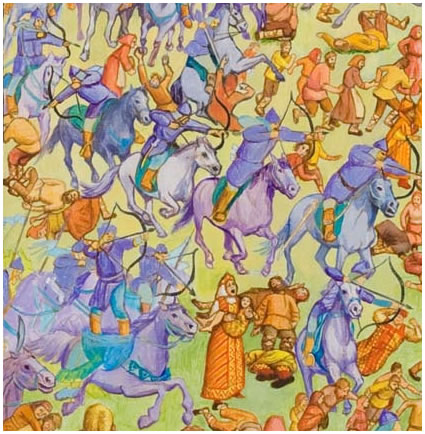

Detail of Mongols in middle panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

Muscovy – later Russia – arose and was forged in an inferno during the 200 years when ferocious, brilliantly-skilled Mongol warriors pillaged, sacked, brutalized, and dominated it – and the centuries following, when the Mongol’s descendants – the Nogay Horde, the Crimean Khanate and others – continually raided and plundered it.

The Mongols’ war organization, tactics, and composite bows were the great military advances of their day. “The level of organization of the Mongol army was not seen elsewhere in the Middle Ages and stands in marked contrast to that of the feuding Russian Princes.”

If Russia was to survive, its fractious princes needed to whip themselves into a unified fighting force under a single central command, and fast.

To portray Mongol attacks, I painted a battle scene filled with fierce Mongols terrifying Russian peasants and nobles. Continued below image.

Detail of center panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

For the models I needed to paint from, I collected photos of present-day archers shooting Mongol-style bows from horseback, and drawings of Mongol battle-wear.

I painted Russians of all classes running for their lives, and used color to differentiate between them and the invaders: indigos, purple, blue for the Mongols, and warm oranges, reds, yellows for the Russians. This make the two combatant sides immediately “readable” by the viewer.

I wanted to convey the tragedy and terror experienced by individual victims, so I conceived a Russian peasant woman (right) and a noblewoman (above) each holding a wounded child. I balanced color and composition in such a way that the peasant woman stands out from the crowds of people running and shooting.

The necessity for Russians of all classes to unify beneath a single commander presented the tsars with an opportunity to amass vast power and wealth for themselves. Russians of every level of society, desperate for protection against enemies, ceded independent power bases to their defender, the state.

The state leveraged this situation to its own fullest benefit.

Detail of central panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

So my triptych’s AUTOCRACY character is a satirical visualization of how the tsars as a group took advantage of five centuries of nonstop attacks on the Russian people to secure their absolute rule: autocracy.

Europeans, too, sought protection against enemies from their monarchs. Yet tsarist dictatorships didn’t develop there. What was different in Russia?

Even after the Russians threw off the long Mongol occupation, they were far from safe. The economy of the neighboring Crimean Khanate and other nearby Hordes was based on the slave trade: abducting and selling Slavs. So virtually every summer, Tatar raiders rode north across the steppe into Russia, kidnapping thousands of people to sell into slavery in the Black Sea slave market.

These raids occurred not every 10 or 20 years, but essentially every year. Over several centuries, hundreds of thousands of Russians were seized as slaves.

Geographic relationship of Russia to Crimean Khanate and Ottoman Empire

Our very word “slave” derives from “Slav.” No population in the world other than Africans have been enslaved more than Slavs.

A glance at a map (right) shows why Russia was so vulnerable to yearly attack. There was nothing but wide open steppe between Russia and the Crimean Khanate with its slave market (and Ottoman slave-purchasers directly across the Black Sea). Highly mobile, skilled raiders could pour across the steppes each summer, capture thousands of Russians, and head back to the huge international slave market, Caffa, a straight shot across the unobstructed plain.

Russia is by far the largest wide-open plain on earth. Glance at the world maps toward the end of this post if you have any doubts. No mountain barrier protected the Russians. For their state to survive, they had to build their own human barrier.

Details of left panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

In short, Russians lived in the most exposed terrain on earth. They could never stand down from battle-readiness. Their society had to be permanently organized like – indeed it was – a military chain of command.

One way I’ve visually conveyed the relationship between landscape and autocracy is through painting the Mongol battle raging on a flat plain. And I painted AUTOCRACY towering in the midst of this wide-open battlefield, skirts held open to receive the terrorized Russian people.

Another way I conveyed the flatness of Russia’s endless steppes is through song lyrics “sung” by characters I designed for Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible. I wrote these lyrics to the tune of the ubiquitous folksong, Kalinka. Images of the lyrics are above and below. (For more about the characters who sing the lyrics and how I designed them, please see here, here, and here.)

Detail of lower left panel of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

A last way I conveyed the endless, wide-open flatness of Russia – the largest on earth – was through a border around the center panel of the triptych. I created this border from digital images of paintings by the great 19th century Russian painters called the Peredvizhniki. You can find much more detail on my process of building this border here.

* * *

Posts about other tryipychs in the series are here:

Catherine the Great: A Satirical Visualization of Russian History and Society

What is Catherine the Great Singing in Her Triptych?

How I Painted and Composited Catherine the Great (and Stalin)

What If We Had a 9/11 Every Year for Centuries? “Home Security At Any Crazy Price”

The Most Exposed Terrain On Earth

Portraying the Vast Flatland of the Playground

An introduction to “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes” is here; the artistic process behind it is here.

PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS is a series of artworks that – like comic books and graphic novels – tell stories through pictures. PLAYGROUND’s tales are about modern Russia, “narrated” in song by the likes of Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great.

My whimsical imperial characters sound off through original lyrics I wrote to the tune of the famous Russian folksong, Kalinka. The lyrics are about the “gifts” Stalin received from Tsarist history, the foundation on which he built his country’s most powerful dictatorship ever.

If viewers wish, they can navigate their way through PLAYGROUND’s arias in sequence by following the numbers I’ve painted on each panel.

My most recent PLAYGROUND triptych, Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes (above), is “sung” by Catherine the Great, one of Stalin’s three “fairy godparents.” In Panel 1 below, Catherine gives her blessing from Russia’s past to the delighted, mustached baby Stalin.

Detail: center bottom panel (1) of “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal