This is the introduction to a new series of hand poses which include inanimate objects. The actual tutorial and video demo of pose #9 will appear in my next post.

Meanwhile, you have a bit of homework to prepare for the tutorial: you need to find a good object to hold in your sketch. Please see the last section at the bottom of this post to learn what you’re looking for.

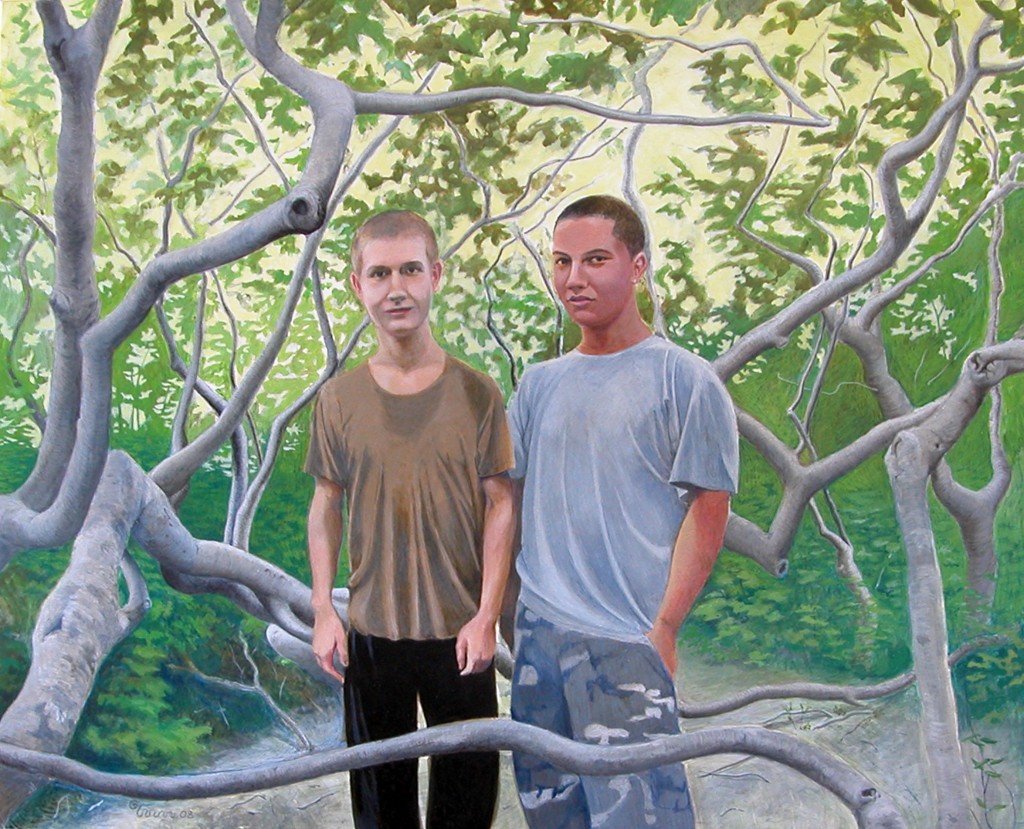

Sketch of hand holding bottle opener

In my next few hand drawing tutorials, I’m going to add an assortment of inanimate objects to each hand pose – to begin with, I chose a bottle opener (right). Over time, we’ll practice sketching the hand from various angles holding items of diverse shapes and sizes.

I decided to introduce inanimate objects because in my kind of right-brained drawing technique, there’s actually no difference between sketching a hand or sketching anything else – as long as you’re drawing some kind of model (a live model or a photo). In my rather Zen approach, you pay no attention to whether you’re drawing a hand or a waterfall. You do this because you need to empty your mind of everything that gets in the way of your seeing the shapes, shadows, and highlights that are actually in front of you.

In pure right-brained drawing you learn to see what you’re drawing in a very abstract way. You look only at shapes, angles, darks, lights.

Parad0xically, this abstract approach can produce hyper-realistic results.

Other types of hand drawing tutorials

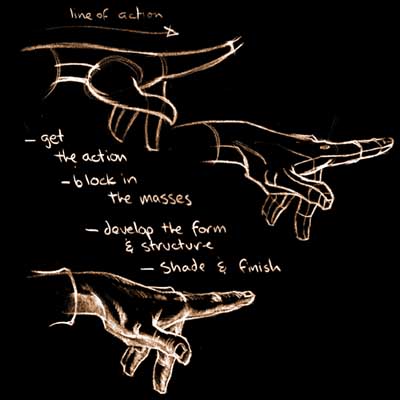

My method is almost the opposite of the approach taken in most hand drawing tutorials. They recommend learning as much as possible about the anatomy of the hand and body proportions, and viewing the hand as made of sub-parts of different volumes.

Illustration from Ron Lemem's hand tutorial. Click on the image to go to this lesson on his website.

For me, learning all that stuff would completely inhibit my drawing, as I wrote in “Me against Da Vinci: What’s the best way to draw?”.

But I encourage you to explore all kinds of approaches to find what works best for you. A couple of good websites to review for non-me techniques are Ron Lemen’s and odduckoasis.

I suspect that learning about e. g. hand anatomy is important if you’re drawing purely from your imagination. If you’re drawing a comic book, for example, you probably want to know how to quickly suggest a hand in an appropriate position without having to find a model.

If you’re drawing from life, though, I highly recommend that you do your best to empty your head of all left-brain information about anatomy or the function of the hand, or anything else. If you hold that information in the front of your mind, it will get in the way of your focusing on what you’re drawing.

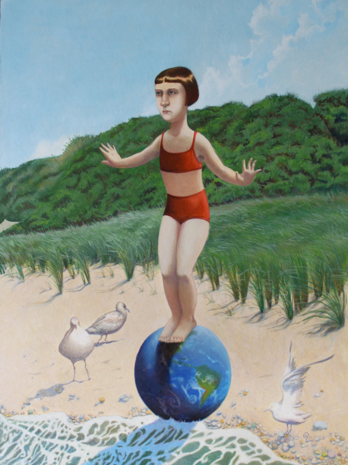

This is an intriguing paradox: you fill your brain with technical anatomy in order to draw from memory rather than from life. But if you want to draw realistically from life, the best approach is the very abstract, right-brained one. I’ve observed this paradox in another earlier post, about Marie McCann-Barab’s paintings (scroll down to the last section, “Yin and/or Yang”).

I’m very interested in drawing what’s in my imagination, these days in my Playground of the Autocrats triptychs. But my preferred method of drawing is still always from life because I find its infinite variations thrilling. So I always look for models that approximate what’s in my imagination, rather than drawing purely from memory. As I wrote then,

For me, the everyday visual world is full of such surprises that I don’t want to just repeat from memory something I’ve drawn or seen in the past. Drawing from my memory of “what an X looks like,” by definition means I’ve developed a somewhat standardized way of seeing and drawing X. For me – and maybe for you – there’s nothing like the magical pleasure of discovering what’s unique about the particular “X” I’m drawing at that moment, and capturing that uniqueness on paper.

Bottle opener I used for Hand tutorial #9 (see next post for demo)

Bottle opener I used for Hand tutorial #9 (see next post for demo)

Your scavenger hunt for your object for Hand Tutorial #9

In the next few days, keep your eyes open for an appropriate object for our first pose of the hand holding an object. The ideal object for your first sketch is something like the bottle opener I chose (right).

Here are the qualities you should look for:

- A fairly simple object – don’t choose something with complicated patterns or writing on it, like a food bottle. In general, an object with some straight lines, rather than entirely curvy, may be easiest for your first drawing.

- An opaque object – don’t choose something transparent.

- A fairly compact object – don’t choose something long like a knife or dowel that will extend far from your hand.

- A mildly interestingly-shaped object – my bottle opener was perfect because of the nice enclosed negative space and the nice, small number of distinctive details.

- If you’re able to find a bottle opener like mine, or an object with a similar size and shape, it may be most helpful. However, if you can’t find that, rest assured the technique will be the same no matter what your object is.

Have fun with your hunt, and see you next post!