“…the truth is, it’s hard to suggest freedom of choice for artists and [then to] advocate hard and fast rules.”

Timothy C. Tyler

___________________________________________________

One rule many portrait artists follow is to never paint their subjects smiling, especially if the smile is wide enough to reveal their teeth. These artists generally feel that since a smile involves muscle contraction, it produces uncomfortable tension in the portrait. A fully relaxed face, they feel, allows the viewer’s gaze to wander over and appreciate the subject’s features. Some portraitists contend that only the unsmiling face can have lasting appeal across many years. The wonderful contemporary Dutch portrait painter Rene Tweehuysen wrote, “A broad smile (showing of teeth) is not really to be recommended, and in the long term can lose its appeal.” American Bart Lindstrom said: “Great art is about subtlety. That’s why, when I paint portraits, I prefer the quiet, timeless expressions of a relaxed face over one with a large smile.”

The historic development of photography has made it much more possible for artists to paint fleeting facial expressions, including smiles. Some top portrait artists are now painting smiles full of character.

Today’s portraitists’ widespread use of photos as reference tools has added a new twist to the debate over whether portraitists should paint smiling subjects. Margaret Carter Baumgaertner, a leading American portraitist, has provided a quintessential description of the limited role traditional portraitists feel photography should play:

“My policy is to work from life as much as possible. In the event that one needs to work from photographs, the photographs should represent life. When taking photographs, I place the subject in a pose that they could hold for 40 hours if they had to. Some people I paint with a pleasant smile. But the photographic “Say cheese” smile is actually a fairly recent phenomena. You want to stay away from the candid shot. Something that obviously came from a camera.

“What do you do if the client insists that there be a big grin? I talk them out of it. I explain, in a very nice way, that we are making a painting not a photograph. I bring a big book of masterful portraits (Sargent, the Early Portraits is a very nice volume) as well as my portfolio, and ask them to envision what their painting will look like. I explain that if we do a big grin, we can’t see their child’s beautiful eyes. I explain that in time they might become tired of seeing this toothy grin, while if we have a more pleasant smile or contemplative look, that they will be drawn into the eyes, the mood, the moment of the painting. I explain that we are creating something that their great grandchildren will cherish, that we are together producing a work of art that might someday hang in a museum.”

A lively debate over portrait smiles and teeth has taken place on the online Portrait Artist Forum, marshalling the best arguments on each side. It’s very worthwhile reading through this thread because whichever type of portraits we paint, we can learn something from “the other side” to apply to our own work.

For example, Alexandra Tyng feels that wide, toothy smiles often appear static, while other artists note that smiles distort some facial features, e. g. making the eyes smaller. On the one hand, I personally feel that the “distortions” caused by smiles, looked at from another perspective, are actually our language of emotional communication. At the same time, the Forum discussion reminds me that however we paint, we need to be sure our subjects’ faces don’t appear static, and that their features, especially their eyes, aren’t obscured by facial expressions.

One Forum participant gave an intriguing, insightful explanation of why some artists might feel broad smiles cause unease in the viewer:

“Subconsciously, we know that a photo was taken in a fraction of a moment, and so smiling that long is normal…. A painting, however is not done in a fraction of a moment. It takes hours of work to complete. So a big smile is “unnatural,” as it would logically be impossible for the sitter to have sustained it. [W]e’re subconsciously bothered by the logic.”

Other portraitists in the Forum point out that many famous paintings portray positions that could not have been held for more than a fleeting moment. These paintings, wrote Michele Rushworth,

Saint George and the Dragon by Rubens

were meant to convey a transitory moment. I was studying Rubens’ Saint George and the Dragon the other day, which I have attached as one example. I wouldn’t avoid painting smiles simply because people can’t hold one for thirty hours. The model for Saint George didn’t hold his arm in the air for thirty hours either.

Leslie Ficcaglia observes,

No one can sustain a natural-looking closed mouth smile for very long either; it ends up looking forced and stiff…. The same argument … could be applied to many classical paintings, including Degas’ ballet series…; no one maintains a ballet stance that long either. Brueghel … attempted to capture complex activities … as though they were frozen in time. Eakins has a woman with her mouth open in song and a man in mid-leap at a swimming hole.

And there are those classic paintings of ships on roiling seas, yet waves can’t hold a pose. Other Forum artists point out that Van Hals and even Sargent painted fleeting expressions, including smiles and teeth; examples are posted by Tyng and Mike Dodson here.

Leonardo Da Vinci wrote, “Try to be a calm spectator of how people laugh and weep, hate and love, blanch from horror and cry out in pain; look, learn, investigate, observe, in order that thou mayst come to know the expression of all human emotions.” He dissected facial muscles of corpses, and the annotations he wrote to his anatomical diagrams reveal that he was trying to understand which muscles helped to create certain emotional expressions: “h [Lateral portion of the frontalis] is the muscle of anger; p [median portion of frontalis] is the muscle of sadness; … o t [procerus] is the muscle of anger.” (You can see one of his facial muscle diagrams here.)

Rembrandt studied and drew himself with a variety of facial expressions: fear, anger, laughter. You can see these sketches here (scroll up slightly to see the drawings).

There’s no question that in the days before photography, it was extremely difficult for artists to study their subjects’ fleeting expressions, including smiles, in order to paint them. The time required to observe and capture them would have been prohibitive for many artists.

So in the centuries before photography, artists painted many more “holdable” expressions (or non-expressions) than fleeting ones. I’ve written about this in previous posts, so I was delighted to discover that others in the Portrait Forum have had the same thought. Rushworth wrote:

It seems to me that the reason the “old masters” painted more subdued expressions (no teeth) is because they didn’t have photographs to work from that captured those brief flashing smiles. We think of these traditional old portraits and that’s what has created the aesthetic we often try to emulate today.

Ficcaglia agrees: “if the masters had had Nikons we’d see a lot more teeth in their paintings.”

Another likely factor was observed by Michael Georges: in “‘Olden Tymes’ people generally lost their teeth quite early on. Those teeth that remained were not always the nicest to look upon. George Washington was particularly known to have very bad teeth. In the civil war, the requirement for being a soldier was that you have two good front teeth to bite the paper casing off the bullet cartridge.” Marvin Mattelson concurred: “The old masters probably didn’t paint smiles because most of their subjects were missing their teeth.”

So when today’s portraitists strive to emulate the look of masterpieces over a century old, their painting must appear to be created entirely from live sittings. There can be no teeth or real smiles because a broad smile is a giveaway that photos were used.

I suspect that another reason portraiture in the US often tends to have a conservative esthetic is that many Americans commissioning portraits want to present themselves within an old world ethos. They are striving to establish “aristocratic” credentials in a country too young and individualistic to have a centuries-old hereditary aristocracy.

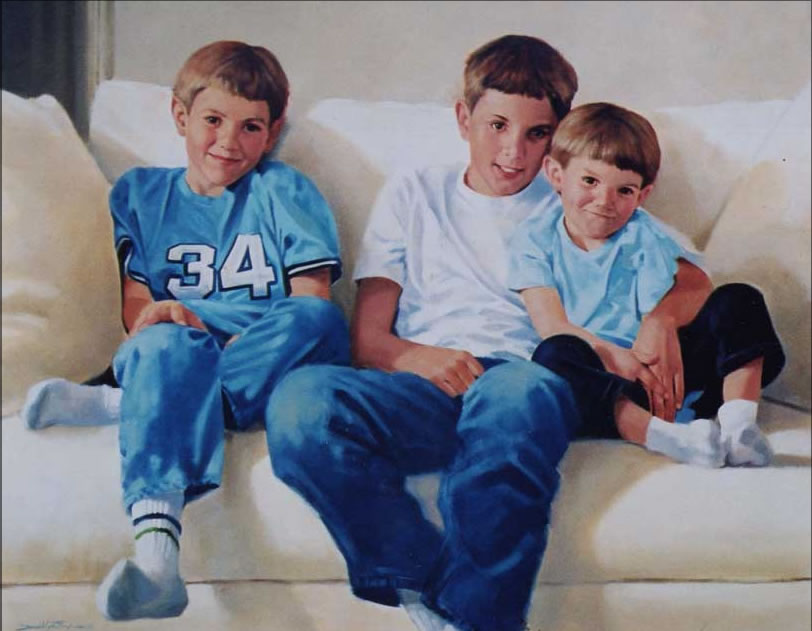

Ironically, parts of the world with centuries of antique portraits on their manor walls are the most adventurous today in experimenting with new forms of portraiture (see Portrait Composition: Old World vs New? below). A British example by Andrew Tift takes toothy smiles beyond what I’ve ever seen by any serious portrait artist in the US. I personally feel Tift’s portrait utterly captures the joyous, free quality of childhood. (Tift is a winner of multiple British National Portrait Gallery awards, including first place in 2006.)

To me, the very specificity of these boys’ expressions conveys far more understanding of their characters than would a standardized slack gaze. This painting gives me a rich sense not just of who these boys are now, but also of what they may become as they grow up. They are completely “at home in their skins” – a combination of masculine-sports-blue and warm caring for each other. The way these boys are painted gives me a sense that they will grow up to be – well, the kind of men I would want my daughter to marry!

So for me, the decision about whether to paint a subject smiling – broadly or slightly, with or without teeth revealed – should be based not on a general rule, but on the character of that particular human being. Every good portraitist seeks to reveal character as well as superficial appearance. And I think people’s characters are visually revealed through their facial expressions more than in any other way. The smile – including the toothy grin – is part of human beings’ infinite repertoire of emotional expression, so I would never want to rule it out as appropriate in portraits.

The smile may even be the expression most particular to each individual over their lifetime. According to Gary Faigin, author of The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression, the smile is the second expression that appears in the human newborn (crying is the first). And it’s “the expression that we carry the most intact from infancy to old age.”

The smile is also the expression of nuance. There are more, and more subtle emotional shadings possible with a smile than with any other expression. Smiles can contain elements of other expressions like sadness or anger, creating faces of fascinating ambiguity and complexity.

Like sadness, smiles can register as a powerful expression even when just barely visible on the face. (Faigin p. 188)

* * *

As I think of my own artistic passion for human expression, it occurs to me that portraitists who favor unsmiling subjects often use the word “introspective” to explain their preference. These artists find more truth revealed in the face of a person looking inward rather than connecting outward. For example, Baumgaertner wrote, “most of my own favorite portraits are contemplative, reflective, and, at times, introspective.”

I happen to be a person who needs a lot of time alone to listen to and follow my own brain’s inner workings. I can happily spend three or four workdays at a stretch alone painting, researching, or writing. I wonder whether my need for aloneness during work time is part of what results in my personal preference for subjects who are engaging and connecting with other people.

Conversely, I wonder whether artists and clients who need to be out and about in public more than I do prefer quieter, more contemplative subjects. After being around the hustle and bustle of life, perhaps these extroverts are looking for some quiet introspection. It would be interesting to hear from different portraitists about whether their underlying values regarding extroversion or introversion in their portraits relate in any way to their own basic temperaments.

* * *

While I can find wisdom in most of the arguments in favor of unsmiling portraits, the one rationale that makes no sense to me is the idea that only an unsmiling face can withstand the test of time. I’ve never seen any evidence provided for this claim (please write a comment if you have some!). What I know is that the portraits I’ve painted of my own children all involve very characteristic smiles – toothy or subtle – that have never ceased to enchant me over the years. The two photos of my son and daughter that I would run back into a burning house to rescue each have joyous, toothy grins that capture the entire essence of their childhood in a single image.

* * *

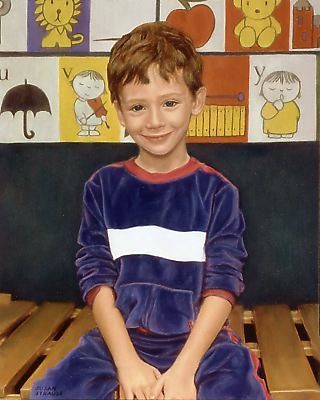

Because smiles still appear in a minority of portraits, I’ll close this post with a few more images of them (click on these images to go to the artists’ websites, where you can find more of their smiling portraits).

I feel all these subjects convey a sense of warm engagement. I feel invited to interact with these very appealing people. I’d like to spend a nice chunk of my non-alone time with each of them.

NOTE: Since I wrote this post a couple of years ago, a controversy has erupted over the 2012 portrait of Kate Middleton, in which she’s painted with a subtle smile. This has brought a lot of new readers to this page. I’d like to steer readers to two discussions of the topic on other websites. One is by the artist Katherine Tyrrell, on the British blog Making a Mark. The other is on the facebook page of the portraitist Sophie Ploeg. Each includes a lively discussion by portraitists such as Alexandra Tyng and others.