“Painting ‘Playground of the Autocrats,’” a February 11, 2021, presentation about my art for Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, in conversation with Alexandra Vacroux, Davis Center Executive Director, is viewable on youtube. This presentation combines my artistic process and thinking with the Russian history it contemplates.

Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Youtube link for Davis Center at Harvard University’s program about my art

Thursday, February 18th, 2021Yakov Kull: Ready-to-wear clothing in Ryazan

Wednesday, June 16th, 2010This is Chapter 4 of my series The World of Jews in Ryazan: Beyond the Pale.” Earlier chapters can be found here.

I had set myself the pleasant task this week of writing about the early 20th century clothing store in Ryazan, Russia, where Yakov Kull worked as a shop manager. What followed was a lot of detective work of the kind that gets me excited, but doesn’t always resolve all my questions. The answers get closer, but at the same time coquettishly move farther away, drawing me deeper in.

For now I’ll present a “progress report” on the intriguing issues that have billowed up as I’ve searched for Yakov Kull and his brother Ber, who worked in the same shop. Maybe some one out there will read it and be able to part some of the mist surrounding this entire project on the world of Jews “Beyond the Pale” in Ryazan. Whether or not that happens, my search will continue for more stories about the lives of these Ryazaners.

The shop where Yakov Kull worked sold men’s and womens’ ready-to-wear clothes, a fairly recent phenomenon at that time. The Kull brothers worked in a new field, as it were, moving beyond the 19th century world in which poorer people made their own clothing and more well-to-do Russians had theirs custom-sewn for them by dressmakers and tailors. According to one article,

“In the early 20th century, Ryazan had only two clothing boutiques and one fashion atelier. These institutions were able to meet the needs of all the Ryazan dandies (men and women).”

This article described one Ryazan ready-to-wear shop, that of Madame Gelyassen, where the fashionable new “tailored suits” for women appeared in 1906. The ready-to-wear suits consisted of a jacket and skirt, in both summer and winter fabrics. The winter versions were made

“of inexpensive, practical fabrics in dark tones – broadcloth, wool. The summer suit was made of silk, cotton linen or duck, the edges trimmed with lace braid. Women of the intelligentsia and emancipated Ryazan women preferred dressing in these suits.

“In the first decade of the 20th century, a third element of the suit began to be sold: the blouse, which had to be lighter than the skirt and trimmed with lace.

Portrait of N. I Petrunkevich, by Russian painter N. N. Ge

“The suits of women who came from the villages to work in production were called ‘parochki:’ a fitted women’s jacket and flared skirt of the same fabric. It combined the traditions of Russian folk costumes and European city fashion. On the bodice of the jacket there was usually a lace insert.

“In the cold season, women wore capes – short fur capes often with a hood or a coat over their suits.”

So the clientele of Madame Gelyassen’s ready-to-wear shop appears to have been both educated women and rural women who came into the city to work in some kind of production.

In fact, the description of “parochki” worn by the latter sounds very close to women in a painting I just finished of Russian peasants. To the right is a detail of my painting, which is based on old Russian photos from the time period. The entire painting can be seen here.

It seems very possible that Madame Gelyassen’s was the ready-to-wear shop where the brothers Kull worked. I would love to know stories of their interactions with customers of various backgrounds who came into the shop looking for one of the versions of these suits. What were the daily dramas of the Kull brothers’ lives in the ready-to-wear shop?

One group of women who continued to have their clothing custom-made, as opposed to buying ready-to-wear, were the very wealthy. These women rushed to the latest styles when a new fashion, influenced by Art Nouveau, became all the rage in Ryazan, according to designer Elena Kroshkin. These were high-waisted clothes, with fabric in “a great wave from the bodice down,” and “asymmetrical lace draperies, swirling in a spiral around the figure.”

The Kull brothers must have been very aware of their near-competitor, Wulfson’s atelier, where clothes were made to order for wealthy clients. I wonder what the brothers thought of Wulfson’s and his business. Did they envy it or think it was over the top? Or some of both? According to one description,

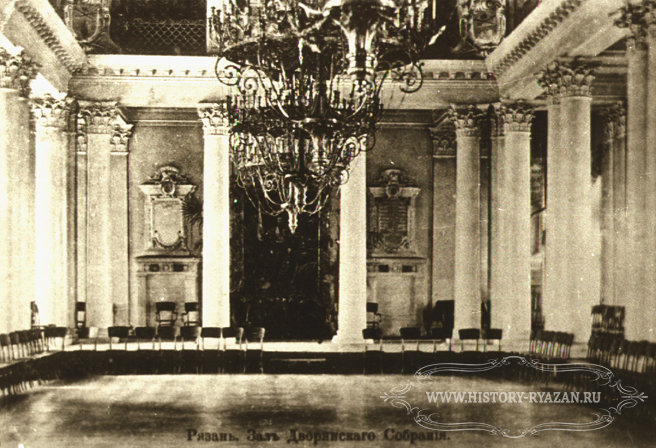

“The girls stood in a queue for [the new Art Nouveau styles] at Wulfson’s – the German tailor, whose atelier was located on Seminary Street…. A month or two before each ball at the Noblemen’s Assembly Hall, the number of orders at the couturier’s increased significantly. The atelier sewed 20 dresses a month, and up to 30 ready-made dresses, brought from Moscow, taken in and adjusted to the figures of the capricious Ryazan ladies. For the “puffy” [presumably fatter] ladies, Wulfson made a special insert….

“Wulfson sewed shot silk, translucent chiffon, tulle with bright patterns and gauze in pale shades. He purchased these fabrics in Moscow. The finery was supplemented with collars of ostrich and cockerel feathers, silver and golden lace.”

Will the real Ryazan ready-to-wear shop please stand up?

I would love to find a photo of a ready-to-wear clothing shop in Ryazan – above all the one where the Kull brothers worked. Photos of the shop would set the scene for us to envision the Kull brothers’ daily-life stories.

But the closest I’ve come after a week of searching has been photos of three ready-to-wear shops in other Russian cities at the beginning of the 20th century. I’ve been wondering and debating with myself which of the three might have been more like our Ryazan shop. Which would be closest to the setting in which Yakov and Ber lived out their everyday comedies and tragedies?

The first photo is of an elegant-looking shop (left side of photo above) in the far northern city of Arkhangelsk, on the White Sea along Russia’s long arctic coast. This photo could easily be mistaken for one of the very upscale streets in Ryazan. Notice the fancy awnings at the windows in the Arkhangelsk shop. The structures on the sidewalks are electric poles of the same type seen on some Ryazan streets as well (see Ryazan photo below).

Ryazan's Postal Street: This trendy shopping street looks almost identical to the Arkhangelsk street, photo above

Leon Kull, great grandson of Yakov Kull, sent me links to two other wonderful photos of ready-to-wear shops in different Russian cities:

Which of these three ready-to-wear shops most closely resembled the one where the Kull brothers worked? The elegant stone building in Arkhangelsk? The freestanding wooden building in Perm? Or the Novosibirsk shop with its unusal Art Nouveau signage? At this point I can’t say for sure. I can only continue following clues which will hopefully bring us closer, not farther away, from history’s truth.

One clue we can pursue is location. According to the article quoted above, both Wulfson’s couture atelier and Mme Gelyassen’s ready-to-wear shop were on Seminary Street, in the northwest quadrant of the city of Ryazan. I don’t have a photo of any obvious shopping areas on Seminary Street. There were both stone and wooden houses along this street, possibly fitting any of the three photos above.

However, Mme Gelyassen’s was on the corner with Cathedral Street (Соборная улица). And Sobornaya was one of the trendy shopping streets in Ryazan. As one author wrote:

“Ryazan city slickers at the beginning of the 20th century bypassed the New Bazaar area. They preferred the ‘trendy shops’ of Postal, Astrakhan, and Cathedral Streets to peasant stalls. In New Bazaar square, the major dealers and buyers were Ryazan peasants.”

This description of Cathedral Street sounds more like one of the first two photos. So perhaps we should envision the Kull brothers ensconced there. (For a photo of another of the three trendy streets listed here, see the the photo of Postal Street above.) Since both educated women and newly-arrived rural girls were listed among Mme Gelyassen’s customers, we would have to imagine that only the most successful of these new immigrants to the city would have been able to afford to shop on this fashionable street.

However, if the Kull brothers worked at a different ready-to-wear shop than Mme Gelyassen’s, our imagined picture may shift a bit closer to the third photo. For according to the same author, New Bazaar’s trading square also included ready-to-wear shops:

“There were whole rows of small boutiques around the square at the beginning of the 20th century. ‘On New Bazaar square and its surrounding streets various goods were sold,’ describes historian Elena Kir’yanova. Here is was possible to find, in addition to grocery shops, ready-to-wear clothing shops and footwear. Here there were haberdashery and leather shops; the first shops appeared for books, candy and even tea. The trade stalls were adorned with womens hats and handbags. More than five hundred types of goods were sold in the retail stalls of New Bazaar.”

Perhaps less-affluent people, including those just arriving from the countryside, bought their ready-to-wear clothing in New Bazaar, while hoping to eventually make enough money to shift to shopping on trendier streets. And perhaps at some point in the future, we will discover which type was where the Kull brothers worked.

New Bazaar Square in Ryazan. Note trading stalls toward the back of the square.

Levontin’s factory in Ryazan: A ghost takes on reality

Tuesday, June 8th, 2010This is Chapter 3 in my series “The World of Jews in Ryazan: Beyond the Pale.” The introductory post about my grandfather is here.

For years my grandfather’s life in Russia was a huge unknown to me. The one bit of information I had was that Boris Bobroff had worked “as an engineer” in a factory in Ryazan before coming to the US in 1905 at the age of 22.

The factory, like everything about my grandfather’s life in Russia, felt romantically mysterious to me. But when my mother, Polly Bobroff, and I finally discovered the factory’s name, it turned out to be a completely unromantic mouthful: the Joint Stock Company of the Ryazan Agricultural Machinery and Railroad Equipment Factory. It was founded by Yekhiel Levontin in 1904.

Beyond that, we knew absolutely nothing, and couldn’t imagine what Boris Bobroff’s life might have been like in this small city southeast of Moscow. For years, my endless online searching turned up absolutely nothing about the factory or about my grandfather anywhere in Russia.

So it’s been with a profound sense of awe that I’ve begun to find bits of information about Levontin’s factory, and so to envision something of what my grandfather might have experienced there. One key to my search success was online tools that made it possible for me to use my now-rusty Russian reading skills to search Russian language websites.

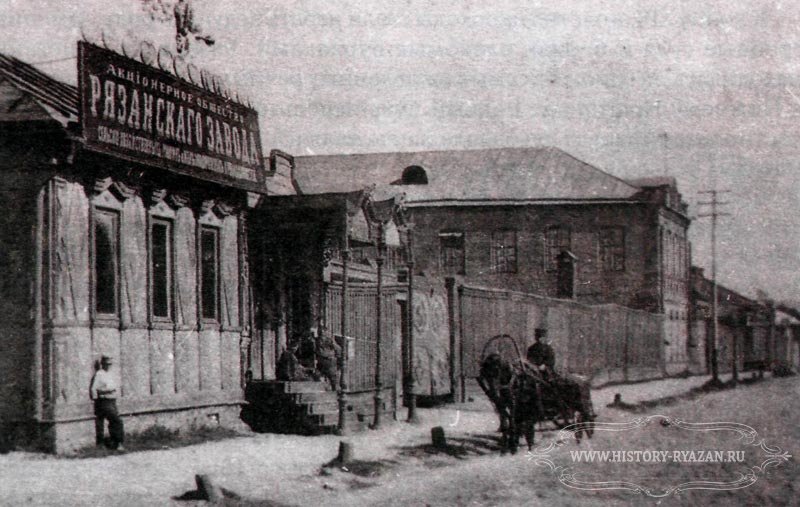

One very important resource in my search has been the website of Ryazan province in Russia. To my utter amazement, this Russian language website has a photograph of Levontin’s factory. The photo is dated 1916, over a decade after my grandfather left Russia. The factory had grown in the intervening years, so it would have been somewhat different when he worked there. Still, it was eerie to see a photograph of this place which until now had been like a ghost to me. Suddenly the place where my grandfather worked over a century ago in Russia began to shimmer into focus.

In the photo, a man in a typical Russian belted shirt leans against the factory. A horse-drawn carriage harnass includes the traditional Russian bell-shaped shaft bow. (This type of shaft bow was also used to harness troika-pulled sleighs, see photo above.) It all felt very evocative to me.

On the factory sign in the photo we can read in the larger letters “Joint Stock Company of the Ryazan Factory.” The caption on the photo reads:

“Factory of Agricultural Machinery and Railroad Equipment. Original Location – on Seminary Street (not far from the Church of Boris and Gleb). 1916 photograph.”

Aha, some new information: according to this caption, the factory was located on Seminary Street. Happily, a search through the massive Ryazan website revealed several photos of that street. Like most of Ryazan’s thoroughfares, it was straight. Like many, it was wide. It appears to stretch off into the steppe beyond the city.

A present-day photo of Seminary Street (below) gives a wonderful sense of the kind of wooden buildings that originally housed Levontin’s factory. Parenthetically, it also shows a wood shingle roof, perhaps of the type made by Avrom Mesigal, who I’ve followed in other posts, here and here.

Wooden buildings on Seminary Street. Present day photo

Another source, though, gives a different street as the original location of Levontin’s factory:

“The history of the factory began in 1904, when the businessman Yekhiel Levontin bought two wooden houses on Malomeshchanskaia Street from the Ryazan merchants Kasin and Kolesnikova.

He [Levontin] lured six highly skilled workers, headed by the expert master Rudakov, from the Telepnev Factory.

He equipped six work places [in his new factory] with a manual lathe, a forge with manual bellows, and fourteen-[horse?]power diesel.

A notarized contract specifies that ‘the plant was to be arranged for the production of mechanical, iron, and other work….’ In 1905, the factory already employed 50 people. Their main products were plows, harrows, and various orders for the railroad.”

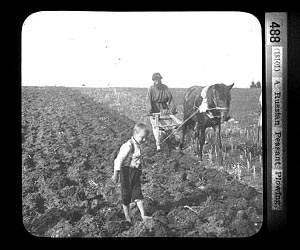

Russian peasant plowing fields. Use of hand plows continued well into the 20th century in Russia.

Because my grandfather worked at the factory in 1904 and into 1905 at the latest, he must have been one of its first workers. According to the letter of recommendation about him, signed by Levontin, Bobroff had been “hired as a worker but was performing the function of an engineer.”

In trying to envision Boris’s daily routines, I tend to seize on small details in the fragments I find. For example, from the description above, it sounds like a lot of the work was originally done by hand using the manual lathe and forge with hand-operated bellows, though part of the work was apparently powered by diesel. I wonder what aspect of this manufacturing process Boris Bobroff presumably helped to work out, given that he was doing engineering work.

According to another source, Levontin’s factory produced 82% of the harrows in European Russia, as well as single-plowshare plows and horse-drawn planters. The Russian-style plow and harrow can be seen in the painting below. Another source says that the railroad items manufactured at the factory were switches and crossings.

This painting by Ilya Repin shows the Russian plow and, in back of the 2nd horse, the harrow. Both types of equipment were made at Levontin's factory.

Which of these items did Bobroff work on? I hope I can find descriptions someday. I do know that, later on in the US, Bobroff received a number of patents on his designs for switches for his automobile directional signals. But I don’t know whether work on presumably much larger-scale railroad switches might have inspired his smaller patented versions.

By 1914 – 9 years after my grandfather had emigrated to the US – 250 people worked at the factory. One description at that time says “The main (plow) shop was located in the basement. The assembly shop was located on the 2nd floor of a new building.”

Russian rural school boys: Oral Sums, by N. P. Bogdanov-Bel'skii

A lovely last description of the inside of the factory in 1914 comes from a rural teacher who brought his students – girls and boys – into the city of Ryazan on a field trip from some distance away. The students had taken advantage of the government allowance to school children of a free train fare each year for field trips. They visited the Ryazan Provincial Museum, and were particularly interested (according to their teacher at any rate), by the agricultural exhibit section. A visit to the handicraft museum and later to the local cinema were followed by free tea and biscuits. The next day, the students visited the printing press of Ryazan Life, a local newspaper.

Last, the rural students trooped to Levontin’s factory, where they were welcomed and provided with two tour guides. The students were amazed at what they saw.

“Before their eyes opened the pages of factory life, completely unknown to the rural child. The strange noise, clatter, banging, the quickness of movement…. It was very instructive for the students to see how gradually plows, seeders, winnowers, iron harrows, and so on, were constructed. Students also saw the iron casting, where the bright red molten mass of iron flowed into ladles and was poured out into prepared forms.”

I can envision these children, who until now had only seen the plows and harrows in use in the countryside where they lived. Now for the first time, they were seeing how the implements were made in the far-off city.

On the train home, the children talked excitedly about what they had seen in the city. According to the author of this article,the boys most of all liked the cinema and the agricultural machinery factory, while the girls had other favorites.

Surely these kids were too excited by all the startling new sights they had seen at Levontin’s factory to think about its owner being Jewish – if anyone had even mentioned it to them. But I wonder whether, as they became adults, they looked back on their vivid memories of the trip and associated the factory with the ingenuity of its Jewish founder. How did they put their childhood impressions together with anti-Semitic views they may also have heard around them?

Again, this description of Levontin’s factory comes from a time after my grandfather had left, when it had experienced rapid growth. I hope at some point to find similar descriptions of what it was like when he worked there.