A client requested a portrait of her son’s family based on snapshots taken in a New York City park (click here for my earlier posting on painting from snapshots). In the photos, the family was surrounded by the park’s enclave of greenery. My client hoped I could also include the city street beyond the park, which appeared in another photo. Her son and his family might move out of the city some day, so she wanted their portrait to capture this urban chapter of their lives.

I resonated with the client’s feelings. I’m always eager to portray my subjects’ worlds in the backgrounds of their portraits. Additionally I wanted to include the cityscape because it was a complex, atmospheric visual element to play off the human subjects.

It also created an interesting challenge in the composition of the painting: In order to fit the street and buildings into the background, the family would have to be placed relatively low on the canvas. The city street would appear above them. And because they were sitting amidst a lot of very green foliage, the cityscape could easily end up looking almost like a separate painting stuck incongruously onto the top of the family portrait. Was it possible to create a unified painting with these disparate horizontal areas?

Subject placement in portraits today

The vast majority of portraits place the subjects’ head/s above the horizontal midline of the painting, often close to the top of the canvas. (Heads are most often centered from side to side.) The head is almost always the top-most visual element in the painting. This positioning leaves no doubt as to what is the most important element of the painting: the face and head of the subject.

This type of composition has of course generated many wonderful paintings over the centuries. Here are some terrific contemporary examples. Please click on any image to see a larger version on the artist’s website.

Portrait by Patricia Wilkes

|

Portrait by Jiawei Shen

|

Portrait by Ron Hales |

Portrait by Fanny Rush |

Portrait by Scott Tallman Powers |

Portrait by Ying-He Liu |

Portrait by Christopher Alexander French |

Portrait by Toby Wiggins |

But is this the only composition that can create a successful portrait? The internet allows a survey of composition in contemporary portraiture in the United States and Britain. Four major portrait websites, among others, provide images of many artists’ work:

- For the US, PortraitArtist.com, and PortraitsInc.com.

- For England, The Royal Society of Portrait Painters (therp.co.uk) and CommissionAPortrait.com. (These include artists from other European countries who are represented by these two British agencies.)

In my endless prowl for visual ideas, I’ve surfed through the work of hundreds of portraitists on both sides of the Atlantic (and some in Australia, China, etc). The more I’ve looked, the more I’ve perceived a pattern that I find surprising, intriguing – and puzzling. While it’s true that most portraits on both sides of the pond follow the compositional rules outlined above, our Old World colleagues seem to venture “outside the box,” as it were, more often than we do. Here are some of the many examples of portraits by British artists (and portraitists from other European countries represented in England) in which major visual elements appear above the head of the subjects. As everywhere in this post, click on any image to see a larger version on the artist’s website.

Portrait by Sergei Pavlenko |

Portrait by Jason Sullivan |

Portrait by Susan Ryder |

Portrait by Alastair Adams |

Portrait by Heidi Harrington |

Portrait by Dick Smyly |

Portrait by Jeff Stultiens |

Portrait by Rene Tweehuysen |

Portrait by Fanny Rush |

In fact, there are many portraits by British painters (or Europeans represented in England) in which the heads of all subjects are placed on or below the midline of the painting, with other major visual elements above the heads.

Portrait by Alastair Adams |

Portrait by Rene Tweehuysen |

Portrait by Andrew Festing |

Portrait by Tom Wood |

Portrait by Vincent Yorke |

Portrait by Oisin Roche |

British-represented European artists are also unafraid to allow vast space above their subjects’ heads. They are able to do this without diminishing the importance of the subject, but adding to it.

Portrait by Heidi Harrington |

Portrait by Laurence Kell |

Portrait by Heidi Harrington |

Yuqi Wang, represented by British CommissionAPortrait.com, trained in China and now based in New York, is a master of this technique.

Portrait by Yuqi Wang

Another very effective British/European variant allots a lot of space above the subject’s head, with another dramatic visual element off to the upper side.

Portrait by Paul Brason |

Portrait by Marilyn Bailey |

Portrait by Rene Tweehuysen |

Portrait by Andrew Tift |

Portrait by Michael Reynolds |

Portait by Jeff Stultiens |

In contrast, I’ve come across very few American portraitists who place all the subjects in a given painting low on the canvas. Yet when they do, they are as likely to produce magnificent paintings as the Europeans do. These two, of J. Lindsay Embrey and William Paley, are by Portraits, Inc artists (artists are not identified on this website).

J. Lindsay Embrey and William Paley by Portraits, Inc. artists

June Allard-Berte is a rare American portraitist who has done a number of portraits with major visual elements in the upper half of the canvas, above subjects’ heads that are on or close to the midline. In general, Allard-Berte gives an unusual amount of attention to composition: “Her sense of composition is superb; it is endlessly inventive, elegant, and nearly always strikes just the right balance with subject. It neither over nor underpowers the strength of the person.” http://www.portraitartist.com/berte/bio.htm Allard-Berte’s talent for composition is very special.

Portraits by June Allard-Berté

American Bart Lindstrom rose to the challenge of a high space over a fireplace with a wonderful composition placing his subjects low on the canvas with a brook flowing through a forest above them. Yet Lindstrom doesn’t seem to have used this type of composition elsewhere.

The American Alexandra Tyng has used it several times to create paintings that are real gems:

Portraits by Alexandra Tyng

But these examples are few and far between among portraitists in the United States. Interestingly, it seems that American portrait painters who venture outside standard centered composition are much more likely to place the subject to one side of the canvas or the other than they are to place new visual elements above subjects’ heads. Here are some terrific American examples of placing the subject off-center horizontally:

Portrait by Portraits, Inc. artist |

Portrait by Marvin Mattelson |

Portrait by Garth Herrick |

I don’t know for certain what causes this cultural difference between England and the US (which I believe extends to other issues besides composition). But it’s interesting to speculate. Is it because a country with centuries-old self-confidence in its aristocratic bona fides feels eager to venture outside the confines of traditional portraiture? Is it because Americans see themselves as needing to dominate their surroundings, while the English are either more humble or more secure, so they feel free to allow their surroundings to appear higher than they are? Perhaps the tradition was begun by British aristocrats who felt their stature was enhanced by their chandeliers, high ceilings, and walls covered with paintings and tapestries. Perhaps they saw such finery above their heads as metaphoric crowns that proved their wealth and nobility rather than belittling them. And perhaps from there, the British became used to portrait composition with other kinds of important elements above the heads.

Portrait by Andrew Festing |

Portrait by Richard Foster, no longer available on the internet |

Portrait by John Wonnacott |

Portrait by Alastair Adams |

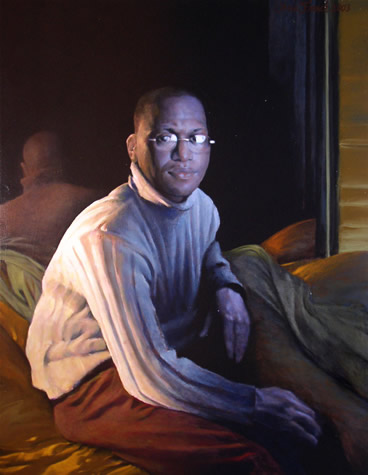

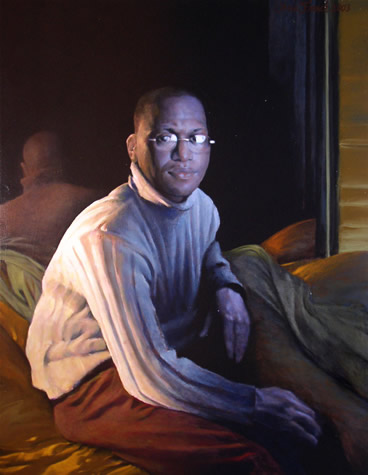

Last, here is my own portrait with the cityscape as the highest element.

Integrating the city street into the background was complicated because, although in reality it had been behind the family, it didn’t appear in the photos I used for them. I had to make judgments about the cityscape’s scale, placement, angle, etc, in comparison with the park foliage, trees, and people. I eliminated certain components from the street photo: a car and several pedestrians. I had hoped to find a way to keep these in the painting, but ultimately they were distracting and not such attractive elements for the eye to wander over. So in the end they got painted out, and I had to extrapolate street shadows and sidewalk to fill their places.

There are several vertical elements that bind the park to the city street: the yellow and gray traffic light, greenery on the left edge, ivy-covered tree trunk, and street light pole. I carefully adjusted each of these so together they would all help ground the street behind the park.

Color also ties the layers together: I altered the actual clothing colors in order to echo the building colors, thus binding the uppermost and lowermost components of the painting. In other areas of the painting, green foliage, working from the very bottom of the canvas up to the trees along the street, also pulls the disparate elements together.

Looking at “out of the box” composition by both Americans and Europeans has enticed me to think more about placing subjects lower on the canvas than other complex visual elements. Given the magnificent paintings that have been achieved by others, I hope it will add to my repertoire and result in unique, rich portraits.