A young Lebanese artist describes how she created her painting, “The Roundabout.”

Vanessa Gemayel: background

Vanessa Gemayel is a young Lebanese artist living in Beirut. She combines a vibrant, gorgeous visual style with thoughtful political and social commentary about the middle eastern city where she’s spent much of her life. (Vanessa was born in Paris and lived there before moving with her family to Liberia. The family had to flee Liberia when war broke out; they then lived in the US for a number of years before returning to their homeland, Lebanon, after its civil war ended.)

One of Vanessa’s recurrent themes is the destruction of the beautiful traditional architecture that gave Beirut its unique atmosphere. The old buildings are being replaced by generic modern buildings that could be anywhere in the world.

Another of her themes is the harmful impact on life in Lebanon of moneyed interests and social pressures for status and glamour. She often uses words – written into her paintings or simply as their titles – to great satirical effect.

Vanessa earned a postgraduate diploma from Chelsea College of Art in London. She has exhibited in Paris at the Centre Vendome pour les Arts Plastiques, and in Beirut. Her “Les Rois Mages” (The Three Magi, above) was selected for the Sursock Museum’s Salon D’Automne exhibition in 2009. Another of her paintings, “Rue à caractère traditionnel,” was shown in the 2010 International Art Exhibition: Lebanese Diaspora, at the Dome City Center in Beirut.

Vanessa writes so well about her work that I have little to do myself beyond formatting her text and photos of The Roundabout in process. (A roundabout is what we in the US often call a traffic circle.)

You can see more of Vanessa’s paintings at the end of this post.

Vanessa’s description of how she created “The Roundabout”

“I started this painting with the idea of depicting a roundabout. A friend remarked at the time that it illustrated very well the feeling of going around in circles that had been overwhelming me.

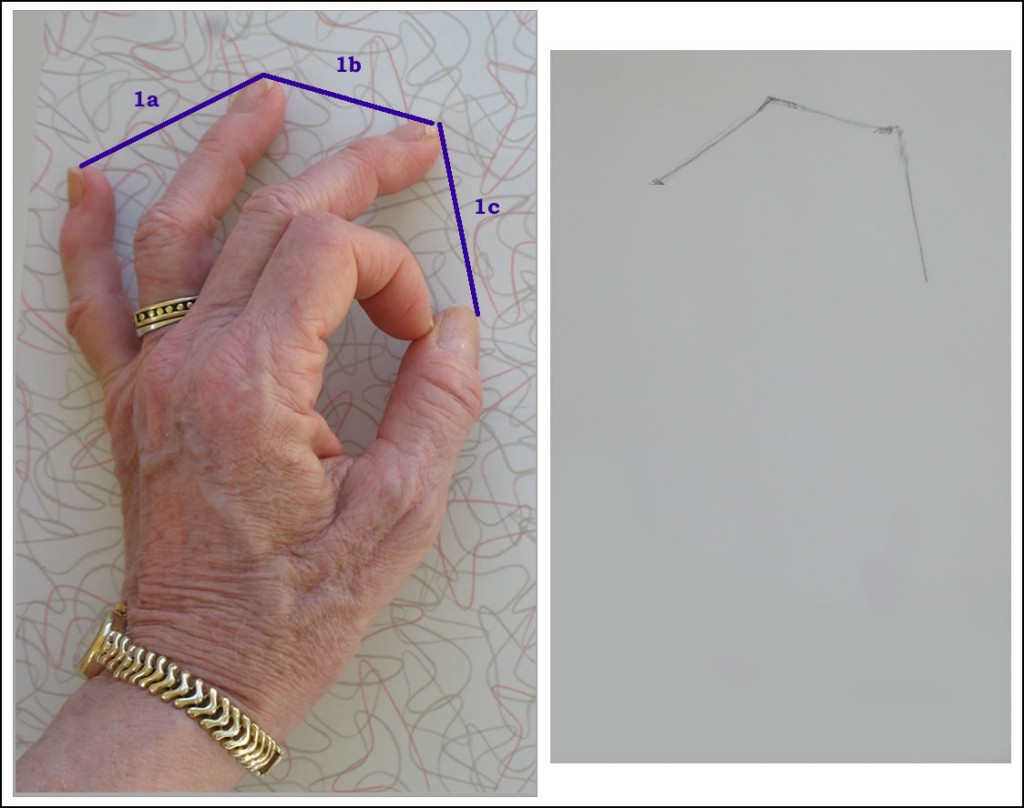

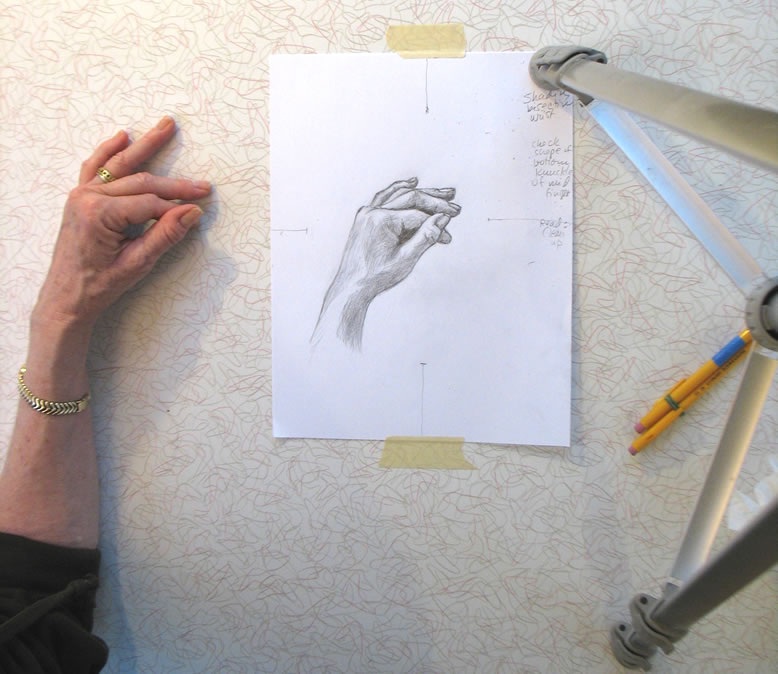

First stage of work on “The Roundabout,” by Vanessa Gemayel

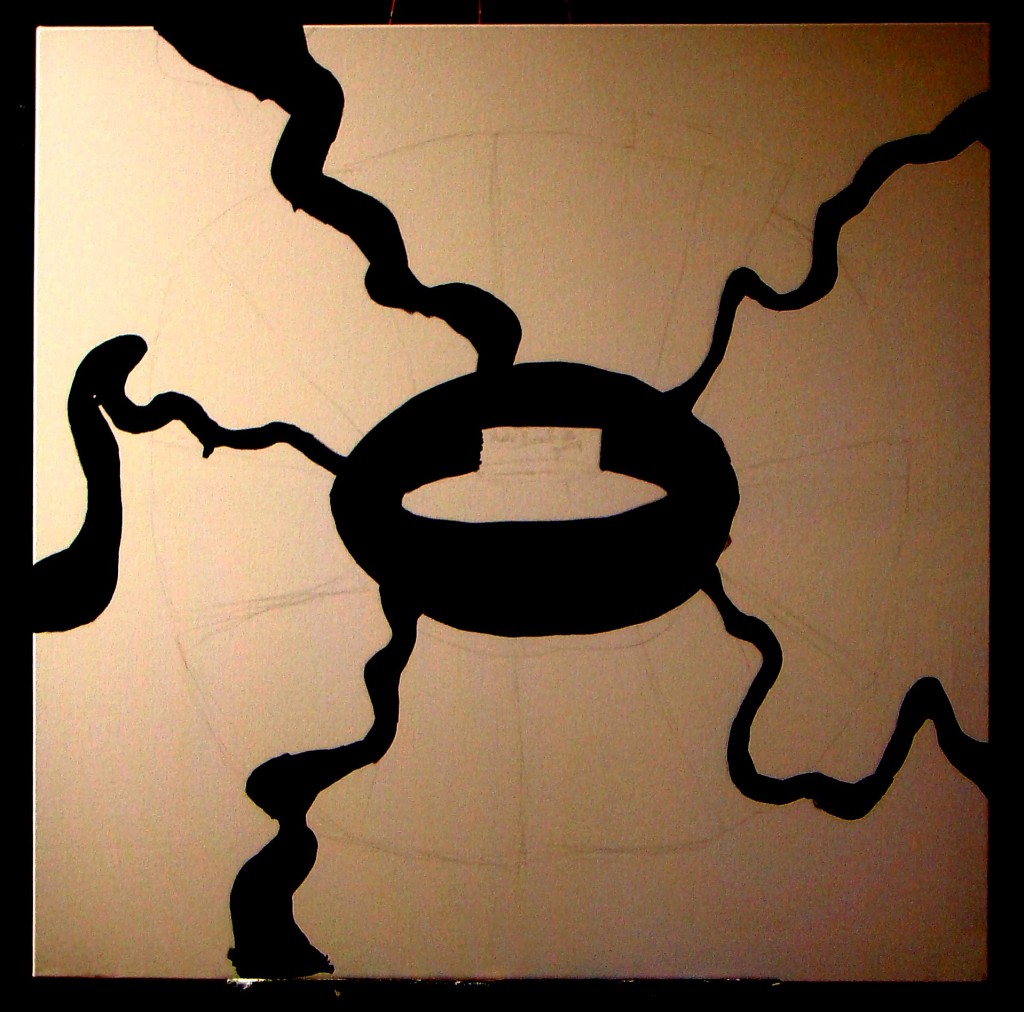

“I drew the outlines of the roundabout and the roads (which I painted in black) then began work, in a circular way, on the buildings (using acrylic and oil). I left no spaces between them because I wanted to portray the city as I was seeing it at the time: crammed and devoid of life and nature.

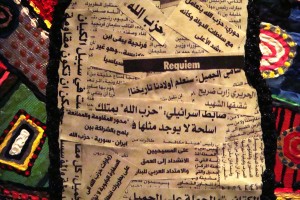

“The painting was almost done except for the most important parts that I had left for last. I got the idea of using newspapers for the roads because I wanted to incorporate socio-political elements, as well as highlight certain aspects regarding urbanization and development.

Second stage – creating “The Roundabout” by Vanessa Gemayel

“L’Orient Le Jour is a French newspaper that targets the intellectual French speaking community in Lebanon. Ironically, many people buy this newspaper just to read the section regarding classified ads, which mainly reports births, deaths and other socio-religious proceedings.

“I used the headlines of this section as themes for each of the roads, which I thought would be well suited to portray the importance of social obligations and social political correctness in this country.

“Each road is made up of ads taken from different newspapers; all are mostly in French and English. Only one road is made of political clippings entirely in Arabic, mainly highlighting names of the politicians who have been in power since the civil war (i.e. for the past 40 years!). This road is the one going straight downwards in the lower left-hand side. The headline from l’Orient I used is “Requiem” in reference to these politicians who keep the country from moving forward and to a language that is losing prevalence to French and English.

Detail from “The Roundabout,” by Vanessa Gemayel.

“The road in the lower right-hand corner, ‘Condolences’, is made up of ads relating to job employment; in view of all the people who are working with a minimum wage insufficient to cover living expenses, or who work (as I so often have) with the promise of a paycheck that never comes.

”Pensées Pieuses’ (Pious Thoughts) designates the road in the upper left-hand corner and is made up of miscellaneous ads such as the sale of nice telephone numbers for thousands of dollars, weather forecasts, civil wedding packages to Cyprus, the sale of high-end cars, designer wedding dresses etc.

“The road in the middle of the left-hand side, entitled ‘Nécrologie’ (Obituary) consists of ads concerning the rent and sale of apartments, buildings and properties. I used this title in reference to the wide scale constructions that are taking place in Beirut. The lack of ethicality, aesthetics, and concern for national patrimony has simply made this process of development synonymous with destruction, careless profit making, and loss of identity.

“Finally, the last road, going upwards, ‘Naissance’ (Birth) is meant to act as an element of hope. (For ethical reasons, I had to conceal the first and last names of the parents as well as dates, and only kept the first name of the child and place of birth).

Detail from “The Roundabout,” by Vanessa Gemayel.

“The road surrounding the roundabout is made up of pictures of people taken from “people” magazines, which are very popular in hairdresser and cosmetology salons. The pictures include local celebrities, political and religious figures and normal people who have hired photographers from the magazine to publicize their birthday, dinner, lunch or whatever occasion fitting (or not), to raise public awareness of themselves, their surroundings and the people that are part of their circle. I then covered most of the pictures with lines and imprisoned them in the road.

‘Most green areas in Beirut are courtesy of some company or another. In this respect, nature is only a ploy to enhance the effect of the ad. For the center of the billboard, I used an ad I found on the cover of one of the magazines mentioned above. It’s a little square portraying the petals of a velvety red flower on which it is written ‘Vous connaitrez tout sur l’orgasme’ (You will find out all there is to know about orgasms).

”The initial title I wanted to use for this painting was ‘Le Bordel’, which, roughly translated, means ‘brothel’ but is commonly used in French to signify “mess.” However I was told it could be a tad bit provocative and decided to stick to Roundabout.”

More of Vanessa’s paintings

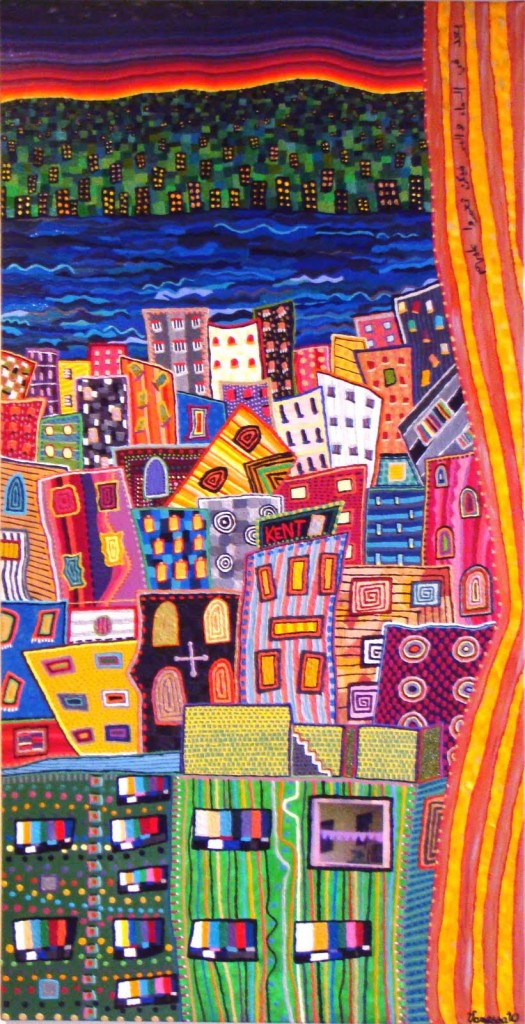

Vanessa’s paintings of Beirut are both highly personal and political. Her “View from the Kitchen” and “View from My Room” (left) portray what Vanessa sees outside her apartment windows. I love the sense of personal engagement with the socio-political life of the city that, for example, her view from her bedroom window provides.

The foreground of this painting includes a crammed jumble of apartment buildings, only a few of which have traditional Lebanese arched windows or tile roofs. While the building shapes are Western, the feel of the city is still vibrant. Beyond the peninsula on which Beirut is located, we see the Mediterranean. And beyond that, plain, boxy, multi-storey apartment buildings march up the steep mountainsides, with no regard to either the spectacular landscape or middle-eastern architectural history. In fact, this type of nondescript construction now covers the rugged, exquisitely beautiful Lebanese mountains all over the country. The Arabic writing on Vanessa’s window curtain in the painting reads: “‘The sea and the sky are still left for you to build on.”

Because the Lebanese mountains rise so steeply out of the Mediterranean – to 10,000 feet only a few miles inland – almost all its roads are full of hairpin turns. We can see these roads snaking crazily among multi-storey buildings in the background of “Beirut?,” another of Vanessa’s paintings (below).

In “Beirut?” and in Vanessa’s art in general, she asks whether this is Beirut or some other random city anywhere in the world, since its architecture so closely resembles that which in the last half century has metastasized across the planet.

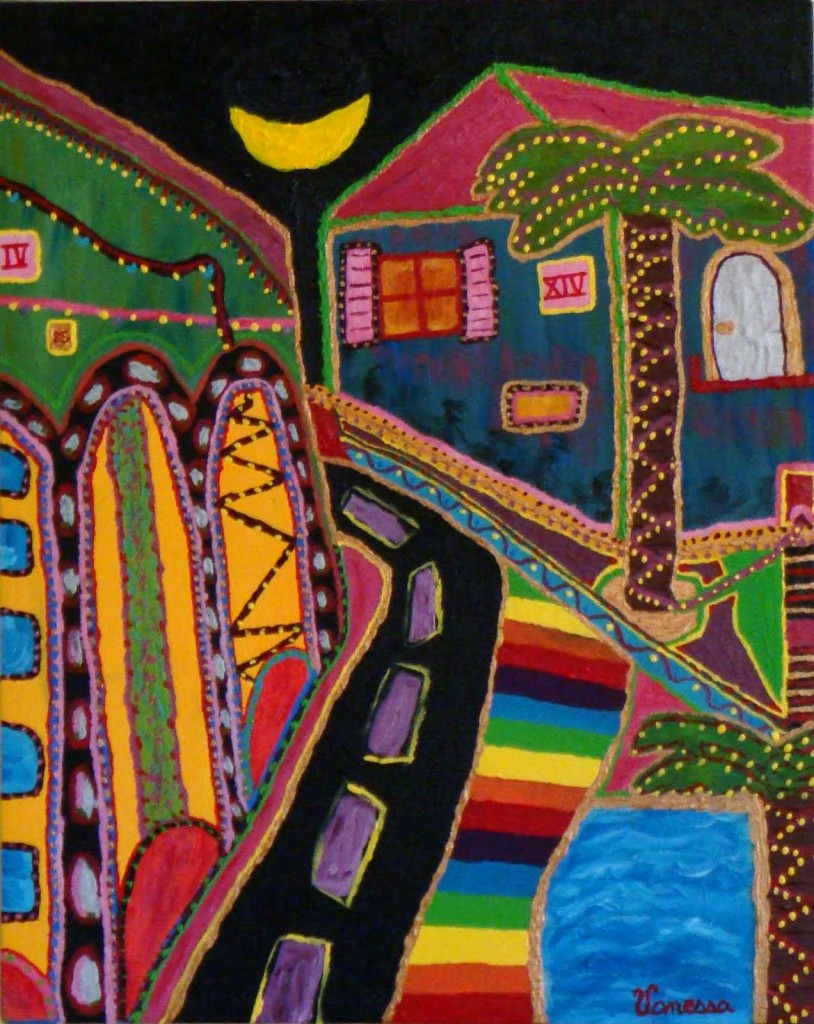

A last painting, “Jbeil” (below), shows another element of Vanessa’s work which I love: roads which take us on mysterious journeys. Jbeil is a small, ancient coastal city north of Beirut. Here, under a crescent moon and palm trees, among low, traditional arch-windowed buildings, life feels relaxed and happy, with the promise of a bit of adventure if we follow the winding road up into the mountains when tomorrow dawns.

Another more recent version of Jbeil is here.