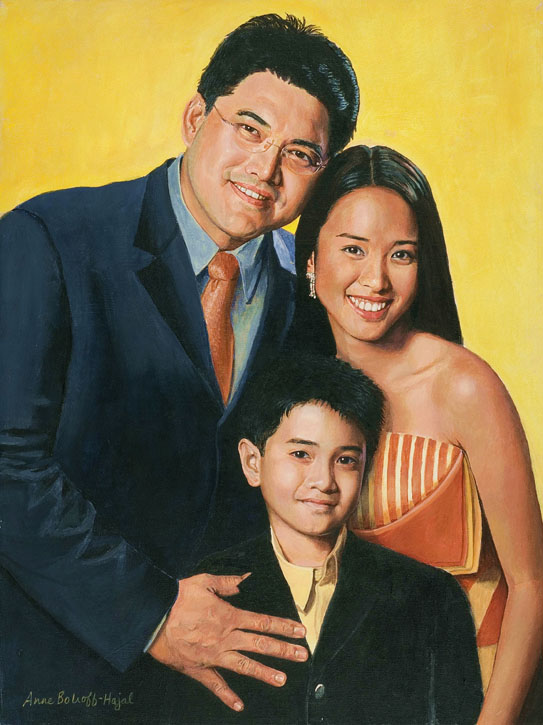

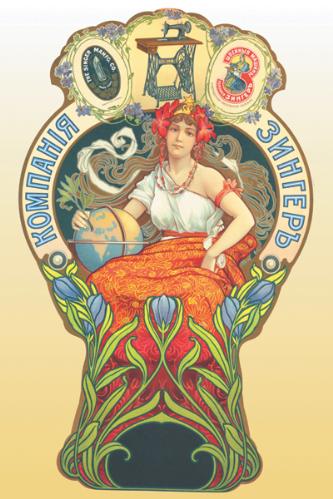

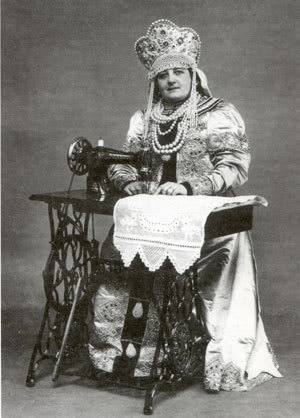

Singer ads portrayed women of many countries sewing at their machines. This is a woman in traditional Russian costume, including a headdress in reality far too heavy to allow bending over her work.

This is Chapter 6 of the thread “The World of Jews in Ryazan: Beyond the Pale.” The previous chapter can be found here.

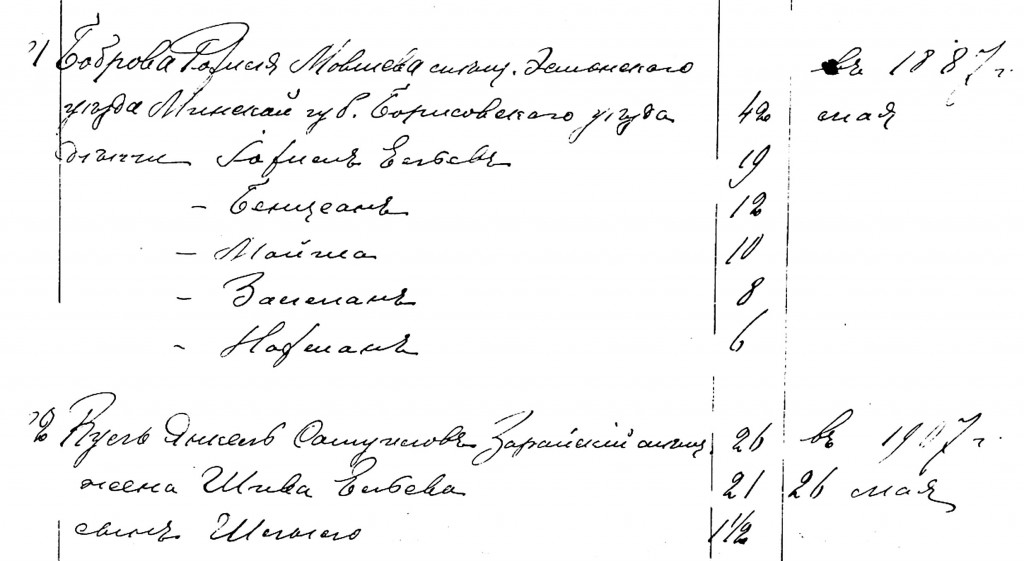

As described in a previous post, Yakov Kull and Rokhilya Bobrova both worked at the Singer Sewing Machine Company in Ryazan, Russia.

What was work like for them on a day-to-day basis? What tasks were they responsible for at Singer? What were their relationships with people they worked with? With their superiors?

Rokhilya almost certainly taught sewing lessons and/or demonstrated sewing techniques on the different Singer machine models. We can be fairly sure of this because these were the jobs the company typically hired women to do in Russia.

More details of what work at Singer was like for such women as Bobrova are hard to come by. One thing we do know is that everyone who worked above her in the shop was likely a foreigner who did not speak her language well. Singer had a very hierarchical structure of managers and auditors. Non-Russians were sent from abroad to fill all supervisory roles. They may have learned some Russian during their time there, but were likely not very comfortable in it.

We can wonder what it must have been like for Rokhilya Bobrova to interview for a job with, say, Germans or Americans, and to come to work every day in a place where all her superiors were foreigners.

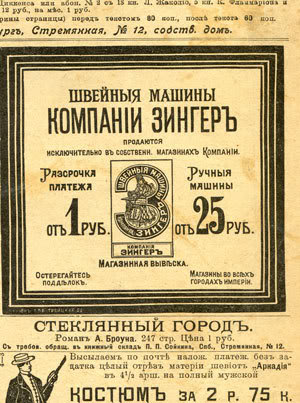

Russian ad for Singer Sewing Machines

Rokhilya – a widowed mother of five – was, of course, herself something of a foreigner in Ryazan, having left her birthplace in Minsk province (now Belarus) in the Jewish Pale of Settlement, at about the age of twenty. Her first language may not have been Russian, either. But she had lived in Ryazan since 1887, for nearly 20 years before the Singer company arrived there, so her Russian was likely fluent.

At any rate, Bobrova would have had a number of co-workers who were longtime Ryazan inhabitants, including Yakov Kull. Local residents were hired for all sales positions at Singer’s because the company realized that to sell lots of machines required salespeople who knew the language and the cultural and social mores of their potential customers. (Domosh)

I like to imagine Bobrova interacting in a friendly way with her fellow employees as she worked each day. One of these fellow employees was Yakov Kull.

Manual for the Singer Model 15, a foot-powered treadle sewing machine.

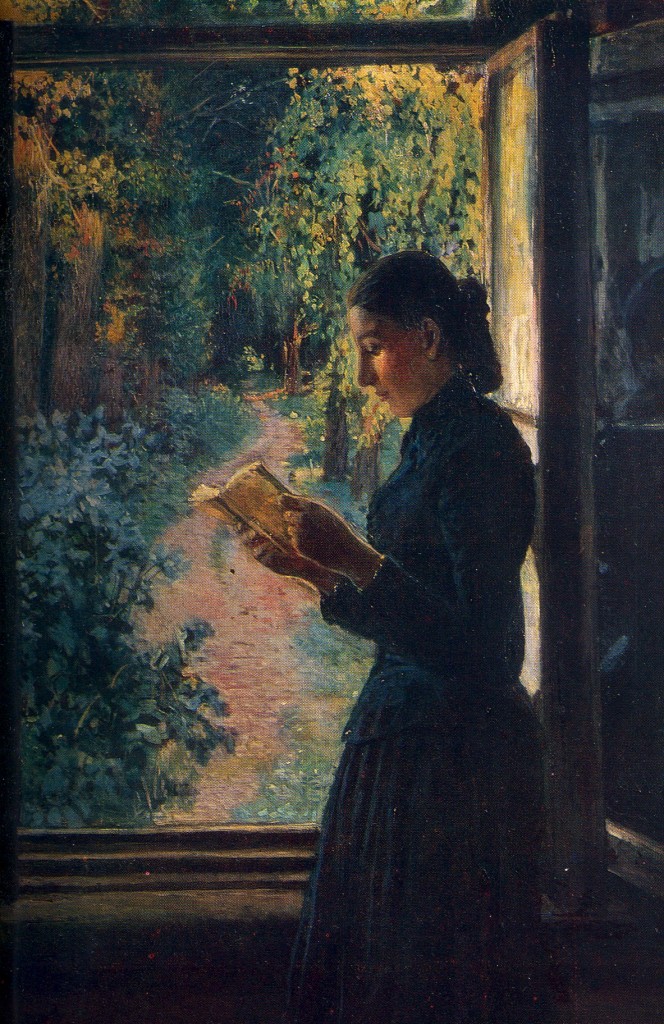

Kull, according to the 1910 Russian Census, was a “sales agent” at Singer’s. These agents – often called “canvassers” in English – were the foundation for Singer’s astronomical success in Russia (and the US). Many worked in Singer’s roughly 4,000 shops in cities throughout the Empire. Tens of thousands more “canvassed” the countryside looking for new customers all across the vast territory of the Russian Empire. Mona Domosh wrote,

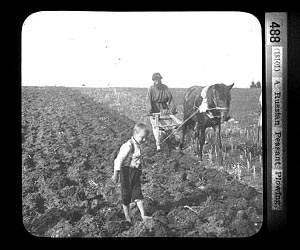

“At the most local level, the Singer ‘man’ on horseback was a common, everyday sight…. In rural areas, this person took daily horseback rides through the countryside, visiting farms and small villages. He (they were all men) carried with him samples of Singer’s various machines and the materials necessary to demonstrate their use, such as thread and fabric. He also carried with him his notebook, where he marked the weekly payments that he did or did not collect. He interacted with customers mainly in their own homes, a visitor of sorts, perhaps known by the family beforehand or at least familiar to them by name and relations.”

The canvassers were “thought to be the key to sales success; they were meant to be energetic, bright, knowledgable about the machines, and honest.” This description definitely seems to fit the enterprising young Yakov Kull, who had moved on to Singer’s from his job as shop assistant in a clothing store.

We don’t know whether Yakov Kull canvassed the countryside around Ryazan or whether he worked primarily in the shop in town. We do know that he had grown up in a neighboring town, Zaraysk, so he would still have had contacts – perhaps potential customers – outside of Ryazan itself. We might wonder whether his former hometown became part of the sales territory he worked.

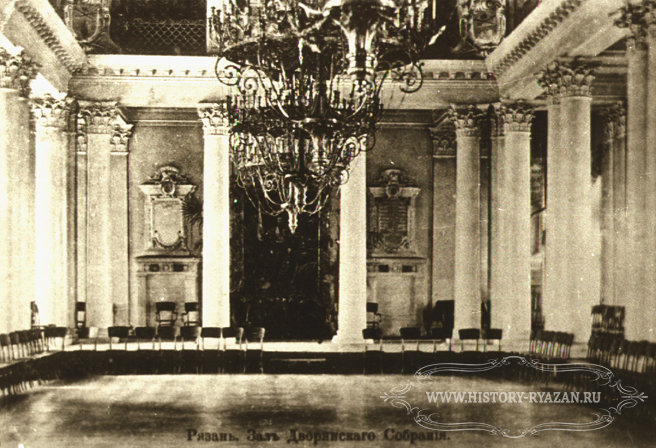

A Singer Sewing Machine shop in Beloomut, Russia, 27 miles southeast of Ryazan.

On the other hand, it’s possible that there was yet another Singer shop in Zaraysk which employed residents of that town. The photo to the left (sent to me by Yakov Kull’s descendent, Leon Kull), shows a Singer shop in another small town not far from Ryazan. The building’s traditional Russian architecture is beautifully decorated with typical peasant carved-wood trim. Note the large Singer sign across the top of the building, which reads “Sewing Machines / Singer Company.” Unfortunately this photo is too blurry to make out the images on the other signs, but they undoubtedly bore pictures of Singer sewing machines. They adorned the facade’s first and second floors, and the corners as well, so as not to miss potential customers coming down the street from either direction.

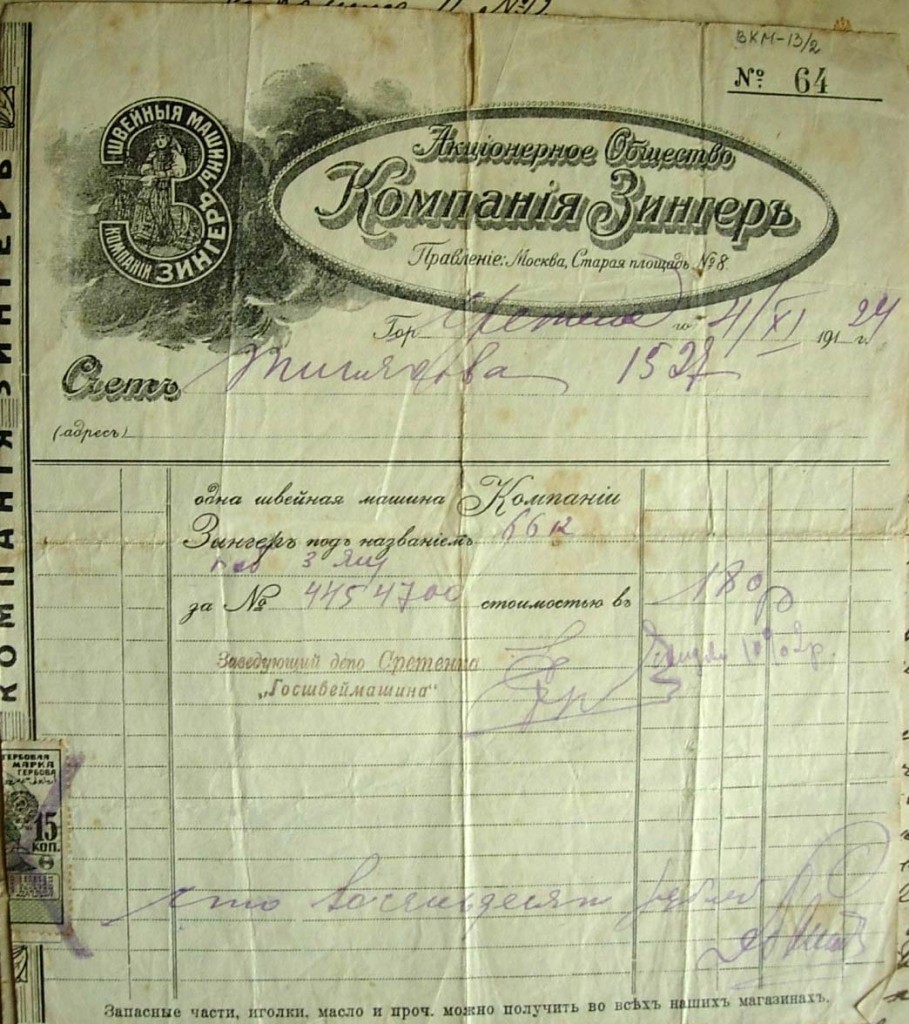

Hand-operated Singer sewing machine. "Singer" is printed on the wooden case in the Cyrillic alphabet, but not on the machine itself.

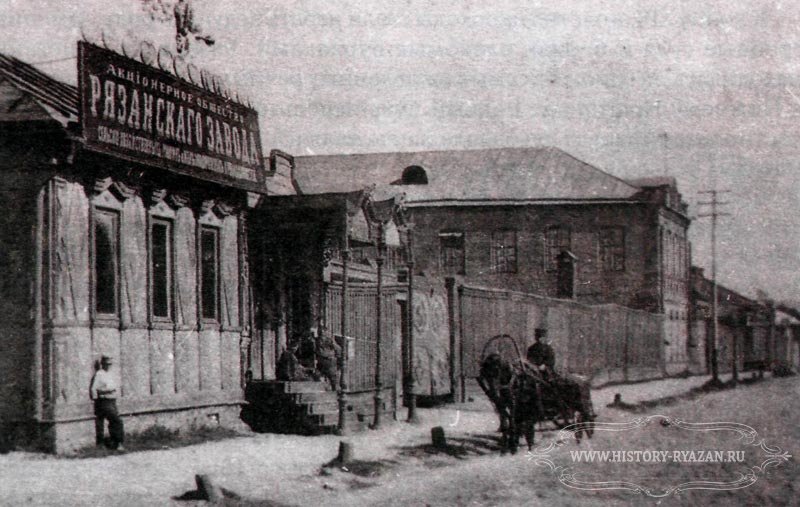

Most customers bought their Singers on installment because the cost of a sewing machine was more than the average Russian’s yearly income. In the United States, Singer installment plans were paid off in two years. But because most Russians were too poor to pay that quickly, payments there were typically spread out over four years.

Russian sales agents such as Yakov Kull were responsible for collecting the installment payments from each of the customers to whom they sold sewing machines. It’s possible that Kull’s wealthier Ryazan customers bought their machines outright. According to fashion designer Elena Kroshkina, sewing machines became part of the fashionable young woman’s dowry at that time, purchased by the parents of the bride.

But it seems likely that many of Kull’s customers must have paid in installments. According to Fred Carstensen’s terrific study of Singer in Russia, the company’s

“army of sales agents collected much of Singer’s income in the homes and workshops of customers. Controlling these monies, which passed through many unsupervised hands, was critical to the financial health of the company. Singer controlled the agents’ sales and collections through ‘hire books,’ coupons, and numbered stamps. Each customer received a book when he purchased a machine. Whenever an agent received a payment, he stuck the appropriate number of coupons in the hire book, then canceled them with a numbered stamp and his own signature. These coupons served both as receipts for customers and as a check on the agent, who had to account for all his coupons when submitting collections and his weekly report.”

Singer Sewing Machine sales bill. Note what looks like a coupon glued into the left lower margin. (This is a pre-revolutionary sales slip, though this one happens to have been filled out in 1924.)

Once a customer made a down payment on a machine, it was not delivered until a credit investigation had been done that indicated Singer would receive all the expected payments. As Domosh explains, this was another reason the company hired local people familiar with the economic conditions of their neighbors.

“Local knowledge of, for example, a bad harvest year or labor dispute at the main factory in town was needed to assess potential credit risks. Therefore, retail employees were familiar with the general economic statuses of their potential customers…. What exactly was involved in this ‘investigation’ is not clear; presumably, a Singer staff member drawn from the local population, and therefore with access to local knowledge, made visits and phone calls to financial institutions and other local institutions. After the appropriate information had been obtained, the machine was delivered and regular weekly payments were either collected or brought to the store or office.”

So Yakov Kull may also have been responsible for credit checks on customers, along with his other duties. For his work, Kull would have been paid a fixed salary, plus commissions on sales and collections.

Carstensen tells us that, because sales agents were collecting large sums of money outside its retail shops, Singer constantly worried about theft. To protect the company, Singer required all sales agents, before being hired, to “deposit a security in the sum of 300 rubles,” which reverted to the company in case of theft.

This 300 ruble security deposit, though, was a massive sum which most potential Russian sales agents could not pay. As Singer rapidly expanded in Russia, its corporate leaders began to realize they would not be able to find enough sales staff if they hired only people who could afford it. Singer also eventually realized it was to their advantage to employ people who were dependent on hard work for the company to earn their living. Sales agents who could afford a 300 ruble security deposit did not have the same level of financial pressure motivating them to work diligently.

So Singer abolished the security deposit in 1908. Yakov Kull began working at Singer at roughly this time. We might wonder whether this change made it possible for Kull to leave the dress shop and move to Singer, where he likely earned a higher income.

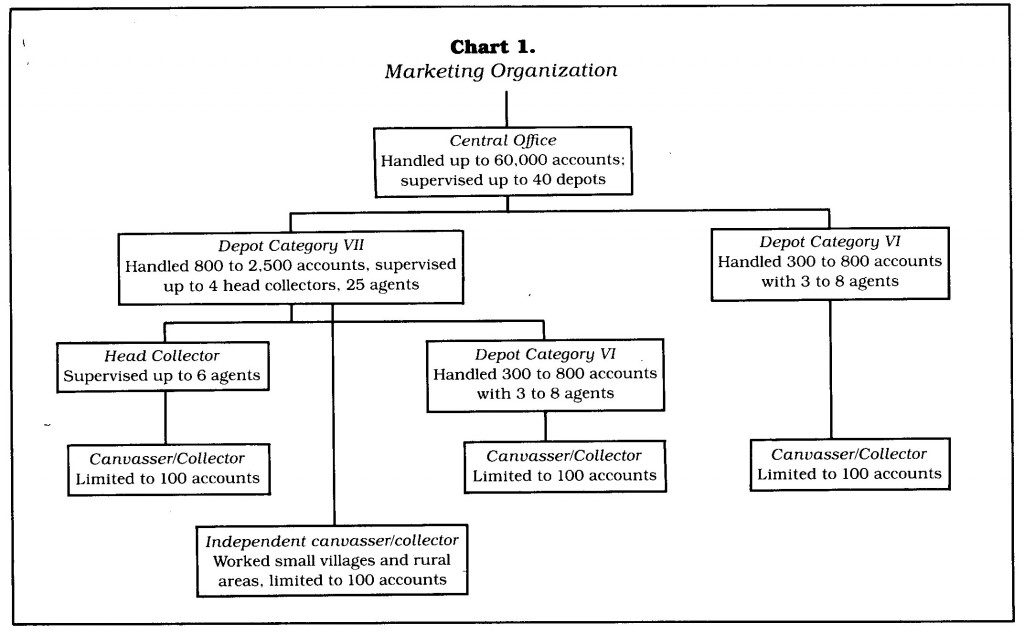

At any rate, both Kull and Bobrova worked each day with a massive, hierarchical structure above them that required them to constantly account for work done and monies collected. Everyone employed by Singer had to make weekly reports which were sent up the chain of command along with receipts, finally reaching corporate headquarters in New York.

Singer hierarchy: canvassers (sales agents) were tracked and supervised by layers of managers above them. From Carstensen, American Enterprise in Foreign Markets.

As I’ve described in an earlier post, because of the low level of entrepreneurial experience and training among the general Russian population, Singer turned to members of minority groups living in Russia, especially Jews, who did have the necessary background.

* * *

As a Singer sales agent, Yakov Kull would have been responsible for selling other sewing items to his customers as well, such as thread and needles, and providing minor servicing on machines.

Small tube with Singer name, containing a pencil which may not be original.

Another item sold was tailor’s chalk, contained in small metal tubes bearing the Singer name in Russian. Leon Kull, great-grandson of Yakov, discovered this fact via yet another extraordinary coincidence which occurred around the time I posted Extraordinary coincidence in Ryazan: Kull and Bobrova co-workers at Singer Sewing Machine.

Leon, who now lives in Israel, happened to be strolling through a flea market the day after he discovered the census records showing that his great-grandfather and my relative, Rokhilya Bobrova, both worked at Singer and lived in the same building in Ryazan, Russia. As Leon emailed me:

“The next day after I found the records about Rakhil Bobrova and my

great-grandfather, I went to the flea market on the Dizengoff Square in

Tel Aviv. Occasionally, as usual at the flea market, I saw an item that

attracted my attention.”

Brass container that held tailor's chalk, with "Singer Company" embossed in Russian (pre-revolutionary lettering)

Of course, Leon bought the little tube on the spot! It had a pencil inside, stuck into the gold-colored cap. However, when Leon later spoke to an expert on the topic, he learned that these tubes originally held tailor’s chalk, not pencils.

As I wrote in my earlier post about Kull and Bobrova, “I suppose the reason anyone searches for information about their ancestors is that they’re yearning to find connections with others beyond themselves in time and place.”

And here once again, Kull and Bobrova’s ghosts were dancing together, this time through the medium of a little brass tailor’s chalk holder!