This post is part of a thread about the world of my grandfather in Russia and in the United States after he immigrated in 1905. Information and photos of his other inventions in the US can be found here. An article about his work as a very young man in Russia is here. A group of articles about his world in Russia is here.

My writing time this week has been swallowed up by an article for an e-zine issue coming out in October about my genealogy research. So I’ve turned over my regular post today to four “guest bloggers:” a couple of sadly-anonymous writers from the year 1916; Congressman “Speedy” Long in the 1967 Congressional Record; and the 2010 National Conference of State Legislators.

They each published articles about my grandfather Bornett L. Bobroff’s invention of the roll-call voting machine.

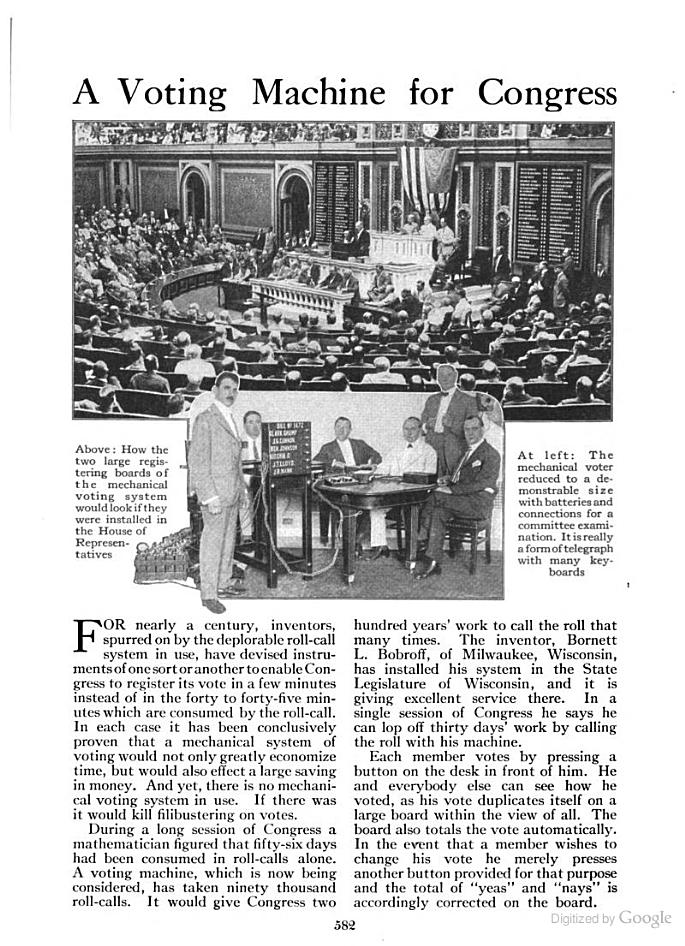

First article: from Popular Science Monthly, 1916

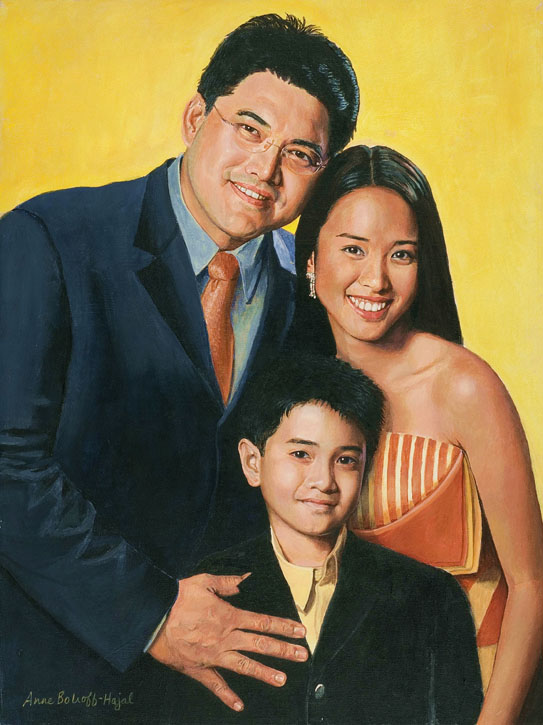

Article from 1916 Popular Science Monthly, with a composite photo showing what Bobroff's roll-call voting machine would look like in the United States Congress. Note the two panels on either side of the dais. These list each Congressman's name, along with lights indicating a yes or no vote.

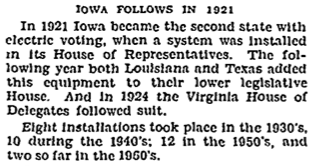

Snippet from 1967 United States Congressional Record listing states in which the electric roll-call voting machine had been installed. Louisiana Representative "Speedy" Long (of the dynasty begun by Huey Long, in whose time Louisiana adopted Bobroff's voting machine) had just introduced a 1967 amendment that the US Congress finally install electric voting.

Bobroff’s most ubiquitous invention was the automobile turn signal, which he patented and manufactured at his Teleoptic factory in Racine, Wisconsin. But he got more press coverage for inventing the roll-call voting machine. Bobroff’s own state of Wisconsin was the first to install this machine in its legislature. Other state legislatures followed.

In 1916, the US Congress was considering installing the machine in the Capitol in Washington DC. This never came to fruition because Congressmen were apparently afraid that speeded-up voting would eliminate filibusters. But meanwhile, there was a brief window of excitement that a Wisconsin inventor, an immigrant from Russia, might make the national scene.

Milwaukee Free Press cartoon and article

My next 1916 guest blogger is the author of a Milwaukee Free Press article about my grandfather, adorned with a wonderful cartoon drawing.

May 1916 Milwaukee Free Press article with a great cartoon drawing of my grandfather, Bornett L. Bobroff

Well, unfortunately this article prints too small for the text to be legible. And it isn’t available anywhere else online. At some point down the trail, I’ll try to post it magnified enough to read. Meanwhile, if you’re writing a school report or doing historical research on the American voting system, shoot me an email, and I’ll be happy to send the whole article to you.

National Conference of State Legislatures article

Last, let’s return to Louisiana. I’m honored that this past February, 2010, the National Conference of State Legislatures decided to reprint a Louisiana article about my grandfather and his voting machine. To see this 2010 article in a larger, more readable .pdf version, click here.