This is Chapter 5 of the thread “The World of Jews in Ryazan: Beyond the Pale.” Other chapters can be found here.

____________________________

“It is an odd feeling to correspond with people whose relatives knew yours 150 years ago.” – Laurie Williamson, a friend doing Civil War research, after discovering some one whose ancestor was in the same Civil war brigade as her great-grandfather.

I now live in NY, USA; my grandfather lived in Wisconsin. Leon Kull grew up in Moscow and emigrated with his wife & kids to Israel

Leon Kull, great-grandson of Yakov Kull, grew up in Moscow, Russia. In 1990, Leon emigrated to Israel with his wife and kids.

I grew up 6000 miles away in Sudbury, Massachusetts, a little town outside of Boston. My Jewish grandfather, Boris (Bornett) Bobroff, had lived in Wisconsin, but died before I was born.

I “met” Leon Kull through the Ryazan subgroup within JewishGen.org as I set forth on an expedition to learn more about my grandfather. Members of this JewishGen geneology subgroup all have ancestors who lived in Ryazan, Russia, at some point in the 19th or early 20th centuries.

Because Jews were only 2-3% of Ryazan’s population, the JewishGen Ryazan subgroup is tiny, about nine people. It was easy to email them. Several responded to me, including Leon Kull. I began to learn bits of how their Ryazan ancestors had wound up living in a place from which most Jews were excluded by the laws of the Russian Empire.

I became intrigued by this small but very varied group of Jewish ancestors: wealthy, aristocratic members of the Polyakov family; Yakov Kull, who managed a ready-to-wear clothing store; the skilled shingle-maker Avrom Mesigal; and my own grandfather, who worked at Levontin’s agricultural machinery factory around 1904-5. I began to write a blog thread, “The World of Jews in Ryazan” about this little group of Jews living “Beyond the Pale.”

Kull family in Ryazan in 1910. Yakov is the adult male farthest right. His brother Ber is next to him.

Last week, while I was researching my most recent post, Leon at his computer in Israel began emailing me information he was turning up in some files he hadn’t checked in a while. A number of years ago, Leon had hired an archival researcher in Russia who’d uncovered various pieces of information – including pages from the 1910 Russian Census listing Yakov Kull’s place of residence and work.

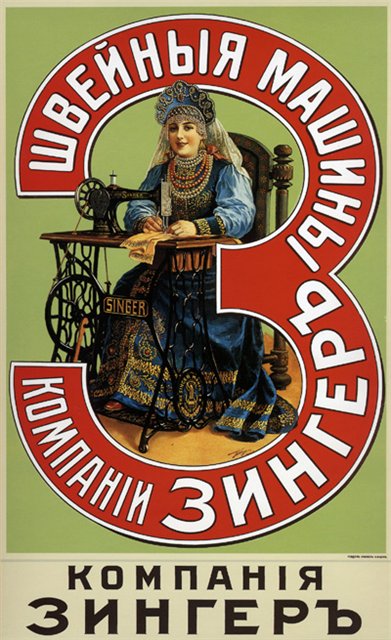

This Census showed that by 1910, Yakov had moved on from managing the clothing shop to working as a salesman at the Ryazan branch of the Russian Singer Sewing Machine Company.

As Leon looked through his files last week, he also suddenly began to discover information about a Ryazan Jewish family named Bobrov. “Bobrov” is the same name as mine, “Bobroff,” just transliterated differently from the Cyrillic alphabet. Given how small the Jewish population was in Ryazan, it’s almost certain that this Bobrov family was related to my grandfather. Here are some of the nuggets Leon sent me:

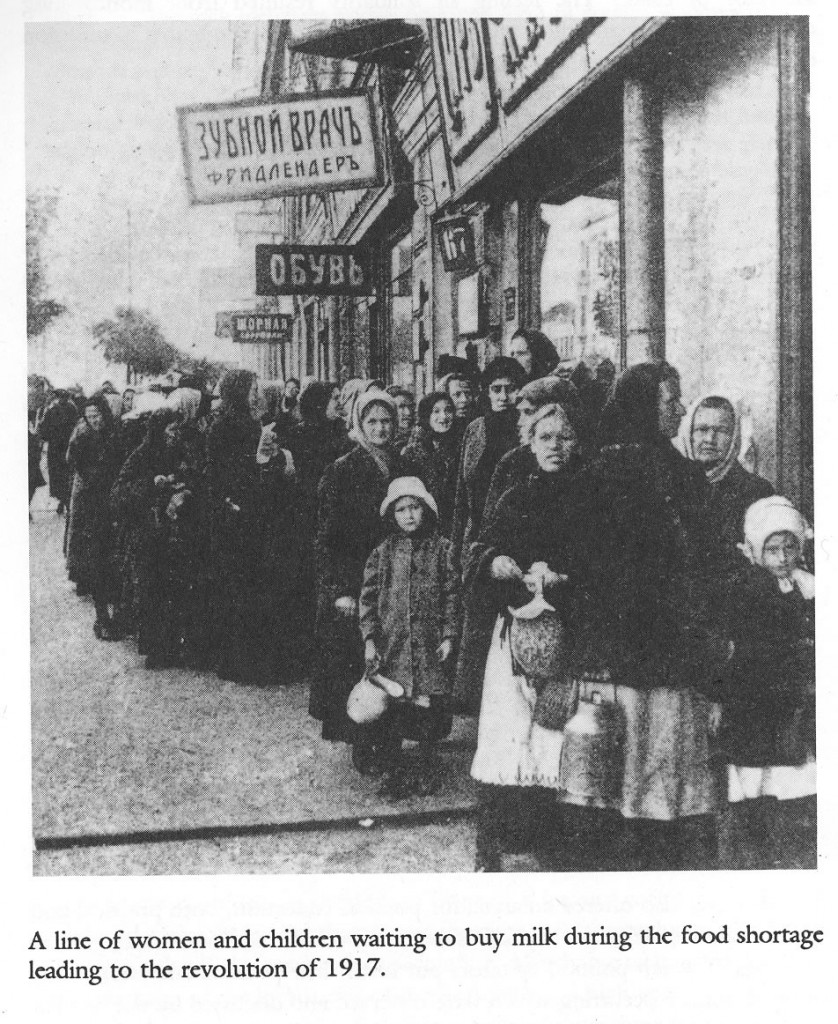

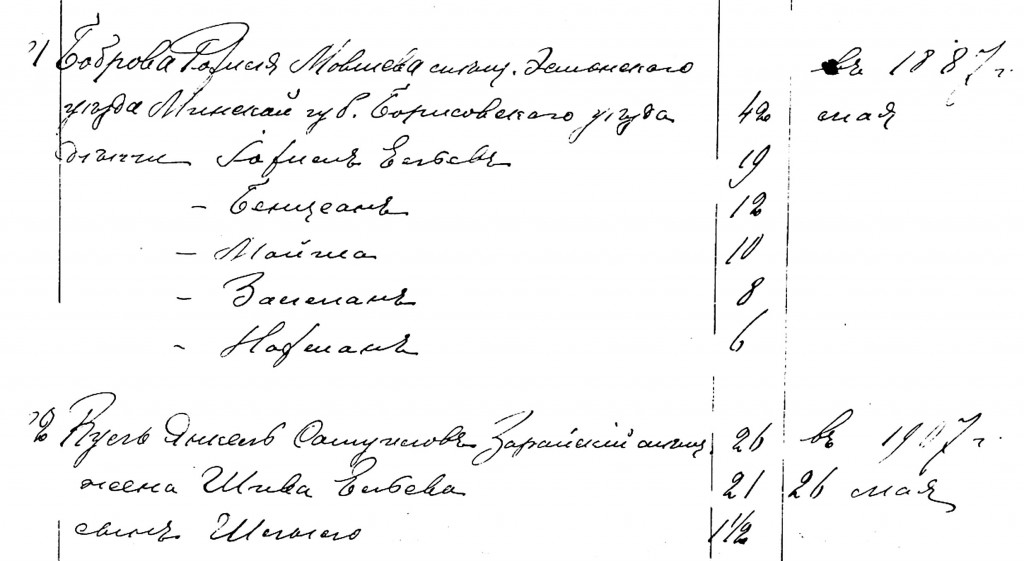

Bobrova Rokhilya Movsheva (daughter of Movsha), bourgeoise, born in 1867 in Minsk province (within the Pale of Jewish Settlement). She settled in Ryazan in 1887.

Rokhilya Bobrova’s husband was Elya Bobrov, born between 1860-65, died sometime before 1905.At the time of the 1910 Russian Census, Rokhilya Bobrova was 42 years old.

Her children were:

Iokhim son of Elya 19

Bentsean 12

Moysha 10

Zalman 8

Nakhman 6

My grandfather, Boris L. Bobrov (or Bobroff) had already left Russia by the time of the 1910 Census, so he would not have been included here even though he had lived in Ryazan.

So, the mystery’s tendrils grew:

How was Rokhilya Bobrova related to my grandfather? She was about 16 years older than him. So she could have been a young aunt or an older cousin. (It’s unlikely that she was his very young mother, because his middle initial was “L,” meaning that his father’s first name began with that letter, so it was not Rokhilya’s husband Elya.) Perhaps in future I’ll track down the connection between Boris and Rokhilya by looking back at Minsk, from whence they came.

I suppose the reason anyone searches for information about their ancestors is that they’re yearning to find connections with others beyond themselves in time and place. Early on, I had thought that Robin Pollack Wood and I might have such a time-warp connection, via her great-grandfather who owned an agricultural machinery factory in Ryazan, and my grandfather, who worked in one. But it turned out the two factories, though similar in name, were actually different.

I had been silly, I thought, to expect such a coincidental connection within the Ryazan subgroup.

So it was with eerie astonishment that, a day or two after Leon’s first finding Rokhilya Bobrova, I read a new email from him. This one had images attached: of a handwritten, double-spread page of the 1910 Russian Census for Ryazan. Listed on line #81 was Rokhilya Bobrova. On the very next next line, #82, was Yakov (Yankel) Kull!

1910 Russian Census pages listing Bobrova and Kull

“Why,” wrote my fellow detective Leon rhetorically, did the two families appear right next to each other? For the answer, he turned my attention to the second half of the Census listing, which noted work place and residence. Happily, Leon provided me an English translation of the faded, scratchy, handwritten Russian.

And there, there was the answer:

“Rokhilya Bobrova works at Singer company (служит в компании Зингер)

Place of residence: Ekaterininskaya Street, Ignatyev’s house (Место

жительства: Екатерининская ул. д.Игнатьева)”“Yankel Kull is a sales agent of Singer sewing machines (Агент по продаже швейных машин Зингер)

Place of residence: the same (as above) Место жительства: там же”

In other words, as Leon explained, Bobrova and Kull worked in the same company, Singer Sewing Machine. They also

“lived in the same house (on Ekaterininskaya Street). And when we look at other addresses on this page, we understand that all 4 families lived on the same street. Authorities compiled this census document by checking one house after another. That’s the reason why Kull and Bobrova appear one after another.”

Wow! Leon and I might live 6000 miles apart, but a hundred years ago, our forebears lived in the same house. And they worked together at Singer’s. They must have known each other quite well.

I felt like Leon’s and my ancestors were not only coming to life. Their ghosts were beginning to dance with each other!

* * *

But what was the quintessentially American Singer Sewing Machine Company doing in Ryazan, on the endless Russian steppes? The Singer sewing machine was such a touchstone for 19th and 20th century Americans that when I mentioned Singer on my Sarah Lawrence College email list, it sparked a whole round of memories of our mothers sewing our clothes with the family machine. To me, envisioning Singer sewing machines in Russia felt like culture clash. An odd company for my Russian ancestor to be employed by!

But Singer machines were in fact all the rage in Ryazan in the early 20th century! According to one Russian blogger,

“The first sewing machines appeared in Ryazan … in 1909. They were sold in a department store at the corner of Astrakhan and Cathedral…. Each machine cost about 30 rubles, the average monthly salary of Ryazan employees. By a year later, the miracle-machines had become the most popular item in the dowries of wealthy brides. The machines were bought by parents. In those days, it was not considered seemly for an unmarried woman to own a sewing machine.”

Another ad for Russian Singer sewing machines. Note the Art Nouveau influence, then popular in Russian fashion as well.

According to another source, Singer sewing machines had come to Russia well before this: “By the beginning of the 1880s the network of Singer’s sales offices, depots and stores had covered the empire. The aggregate number of branches was eighty-one.” Many of the machines were imported from the United States. In addition, in 1902, a large Singer factory, eventually employing 5000 workers, was built in Podolsk, in Moscow province.

So exactly what kind of work did Kull and Bobrova do for Singer?

Well, we have clues for Kull, because the Census listed him as “an agent for the sale of Singer sewing machines.” So Kull was part of the Singer sales force which Mona Domosh describes in her wonderful American Commodities in an Age of Empire: a vast, far-flung, highly organized army of Russian sales agents.

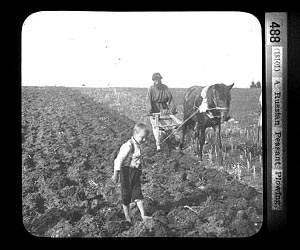

In Russia, with the largest territory of any nation on earth – three times the distance east to west as the United States – these agents sold more sewing machines than in anywhere else in the world besides the US. Sales in Russia went from almost 70,000 in 1895 to nearly ten times that in 1914. The agents traveled the Russian Empire via trains, wagons, and horseback. They floated cargoes of sewing machines thousands of miles down Siberian rivers. There, nomads buying sewing machines paid for them in cattle, pelts and fish (which the sales agents in turn sold for cash).

Back in Ryazan, Kull’s work life was undoubtedly less adventuresome. But Singer’s local operations in Russia were so intricately organized that Kull likely had a job worthy of its own separate blog post. In fact, I’m finding so much almost palpable detail about Singer sales arrangements in Russia that I will postpone a fuller picture of Kull’s job to a later chapter.

But what about Rokhilya Bobrova? What kind of work did she, a woman, do for Singer?

We must remember that, by 1910, Bobrova had been a widow for something over five years. She had five children ranging in age from 6 to 19. A lot of mouths to feed.

What jobs did the Russian Singer company hire women for at that time? Again, Mona Domosh provides clues as how Bobrova may have lived her work days. In the nearly 4,000 Singer shops in towns throughout Russia,

“potential customers could browse the various machines, examine samples of what could be made on each of them, watch demonstrations of various sewing techniques by employees, and take sewing classes. Most of the employees who worked the floor in these shops and who demonstrated and gave sewing lessons were ‘natives,’ and many of them were women…. No women were hired at any level above retail sales and sewing instructors.”

In addition, employees, especially in more responsible positions, “were recruited from ethnic minorities living in Russia, particularly ethnic Germans and Jews,” due at least in part to the lack of commercial experience among ethnic Russians.

Thus it seems likely that Rokhilya Bobrova demonstrated sewing techniques or taught sewing classes at Singer’s.

We can probably assume that Bobrova had originally received her permit to live outside the Pale due to her husband’s profession (I don’t know yet what it was, but hope to unearth it). But Jews had to renew their permits to live outside the Pale every five years, traveling all the way back to their place of origin to get the renewal. Bobrova’s permit came up for renewal in 1909. And now she was widowed.

However, 1909 was the same year Singer apparently arrived in Ryazan. At that point, given Singer’s hiring tendencies, the fact that Bobrova was a Jewish woman may suddenly have become a huge asset. I wonder whether the local Singer store’s management – perhaps even Yakov Kull – played a role in enabling the now-widowed Bobrova to stay on living in Ryazan in her own right.

Detail of 1910 Census page focusing on names Bobrova and Kull