In “Escaping Flatland,” Edward Tufte describes the challenge faced by people who work in the field of visualizing complex information. These designers invent ingenious ways of portraying multi-dimensional data on the “flatlands of paper and video screens.”

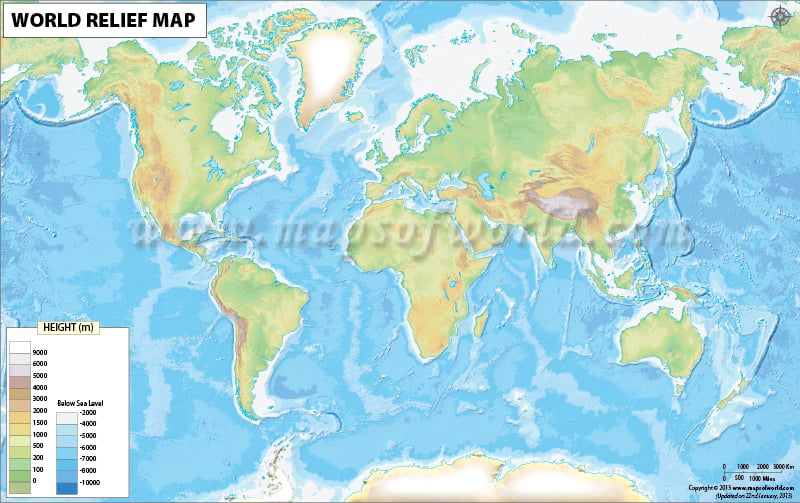

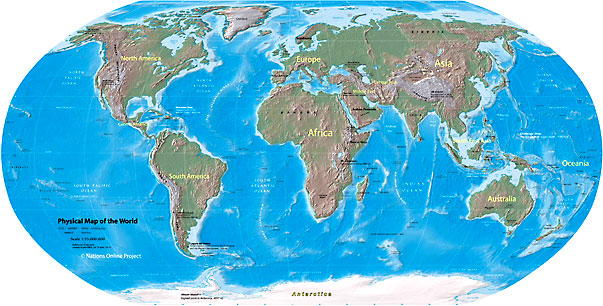

My challenge in the first triptych of Playground of the Autocrats was the same, with a twist. I needed to find a way of depicting 3,500 miles of flat land within the dimensions of my 24″ x 48″ triptych.

Painting a single, particular view of the Russian steppes would not have been so problematic. Many artists have done it magnificently. But what I wanted to convey was that there are 3,500 miles of steppes, and that nowhere else on earth does such a vast open landscape exist. It was a lot of information to visualize in one relatively small artwork!

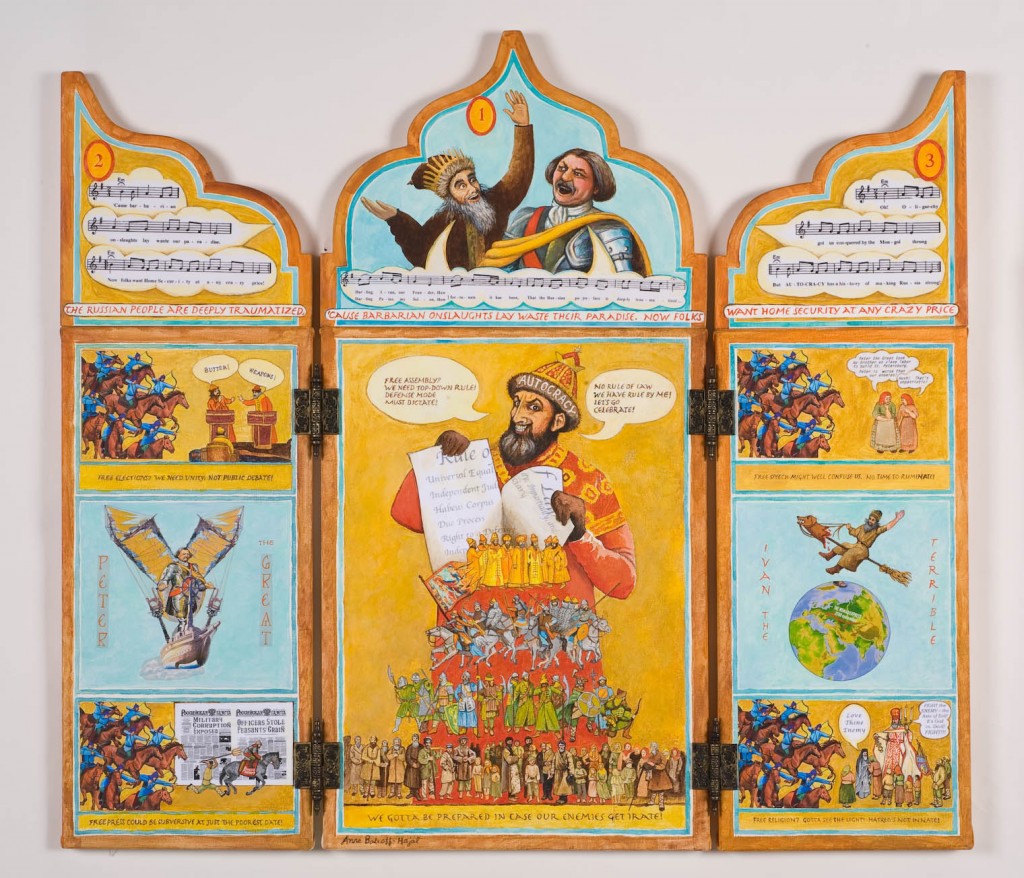

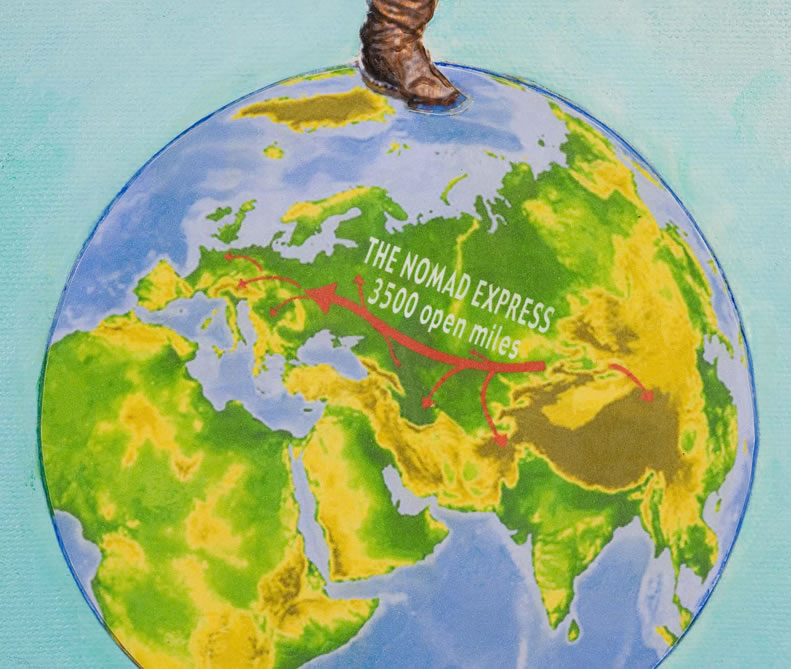

Maps, of course are one excellent way of conveying information about large areas of terrain. As you may have gathered from my last post, I love relief maps! I included a relief “globe” in my character design for Ivan the Terrible (one of Stalin’s fairy godfathers in Playground of the Autocrats). Ivan is on top of the world, dancing on his playground.

Detail of triptych THE MOST EXPOSED TERRAIN ON EARTH: Ivan the Terrible on top of the world

I superimposed the caption “The Nomad Express: 3,500 open miles” across Russia. And I added arrows that marked the Mongol invasions across the vast open land.

Playground of the Autocrat's globe (Detail of THE MOST EXPOSED TERRAIN ON EARTH)

In addition, I wanted to layer in a more evocative portrayal of the vastness of Russia’s territory. Along with the map’s analytic information, I wanted to give the viewer a feeling of what it was to live in that wide-open, vulnerable landscape.

My animation script of Playground of the Autocrats had included a sequence of the Russian land as a reclining Mother Russia. As the lascivious godfather Ivan the Terrible conceived it, she was a peasant woman exposed to “rape by barbarian tribes.” Someday, when an animated version of Playground is realized, I think this will be a terrific sequence, as the terrain morphs into a 3,500-mile-long woman in Ivan’s imagination. But when I tried to create the image in a still form, it became too complex. Maybe I’ll tackle that route in another triptych.

Meanwhile, I had thought of another way of visualizing the endless Russian steppes. I drew on another centuries-old technique: many icons’ main images are surrounded by a frame of smaller images that convey additional information. Icons and religious art in general were the way Bible stories were communicated to illiterate populations. Hence, they are a wonderful model for how we can visualize information today. (The famous art historian Meyer Schapiro wrote a revered book about illustration of religious texts, called Words, Script, and Pictures: Semiotics of Visual Language.)

Russian folktale illustration, most notably perhaps the renowned Ivan Bilibin, followed in this tradition. Bilibin loaded up his borders with wonderful supplementary images that enhance the feeling of the central drawing, if not adding to the story. In the example on the right, the main illustration has a full-color border, while the surrounding text has a sepia-toned border with yet more fantastic, complex drawings.

In my next post, I’ll describe how I utilized the borders of “The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth” in this tradition. You can read that post here.