One of the biggest challenges in much of my personal artwork – and that of many artists – is that I’m painting things that exist in my imagination rather than in the outside world. So I invent “models” from which I draw the imagined scene.

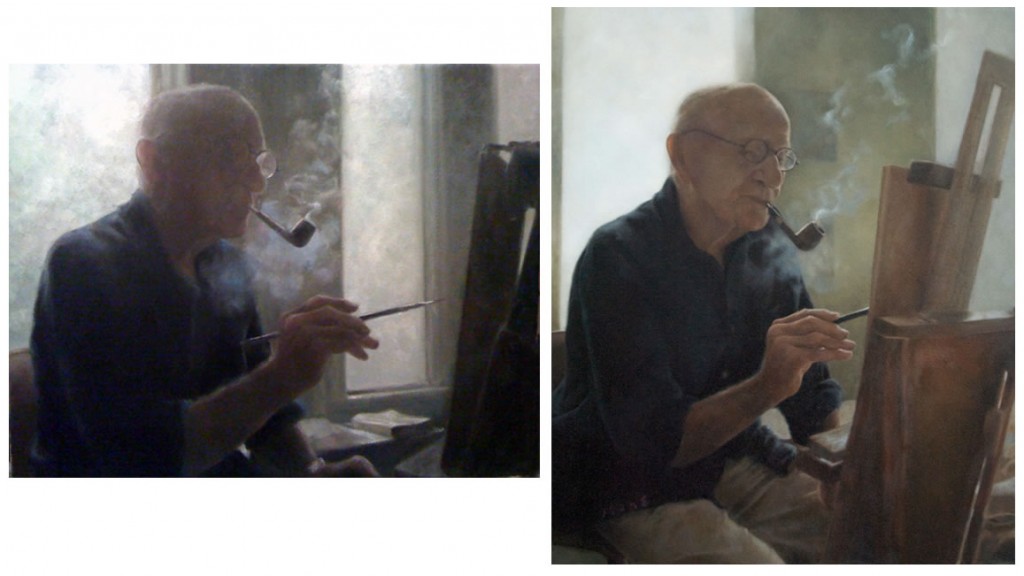

Do you paint from the real…

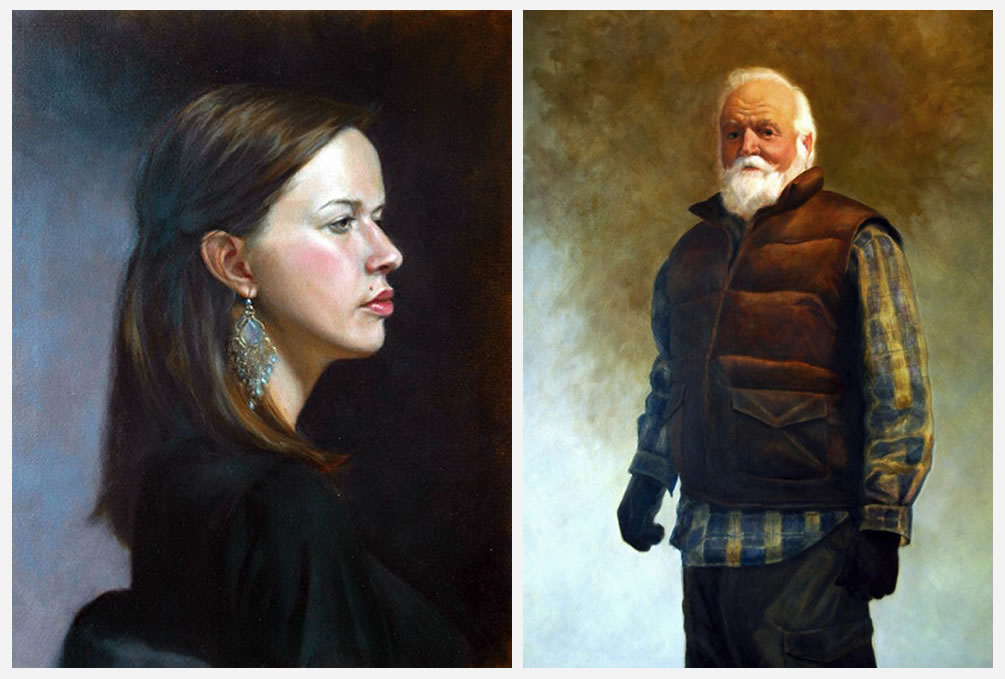

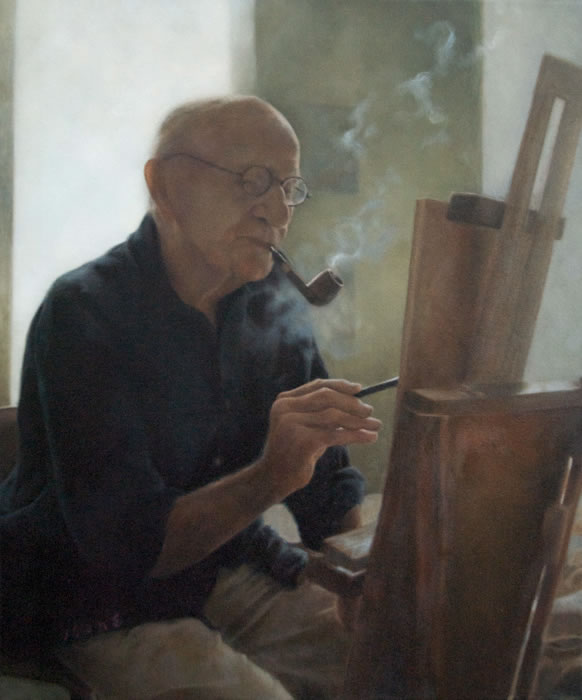

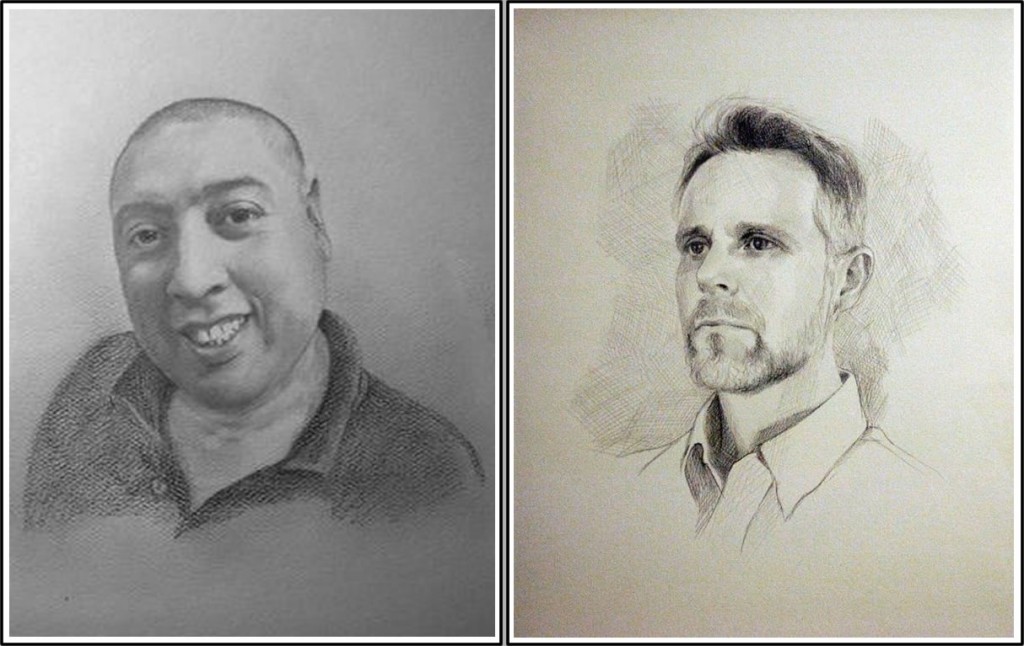

When I paint a portrait, I’m painting a person who exists (or existed). When I do life drawings (the most fun drawing of all), I sketch live models who pose.

When I was a kid, I used to set up still lifes and draw them. In school (I don’t mean art class), I used to alleviate boredom by sketching classmates. When I painted landscapes, I’d go out in the country, find an appealing scene, and paint what I saw. I might make artistic changes in the scene, but it actually existed.

You may be the kind of artist who always paints real objects from the world around you.

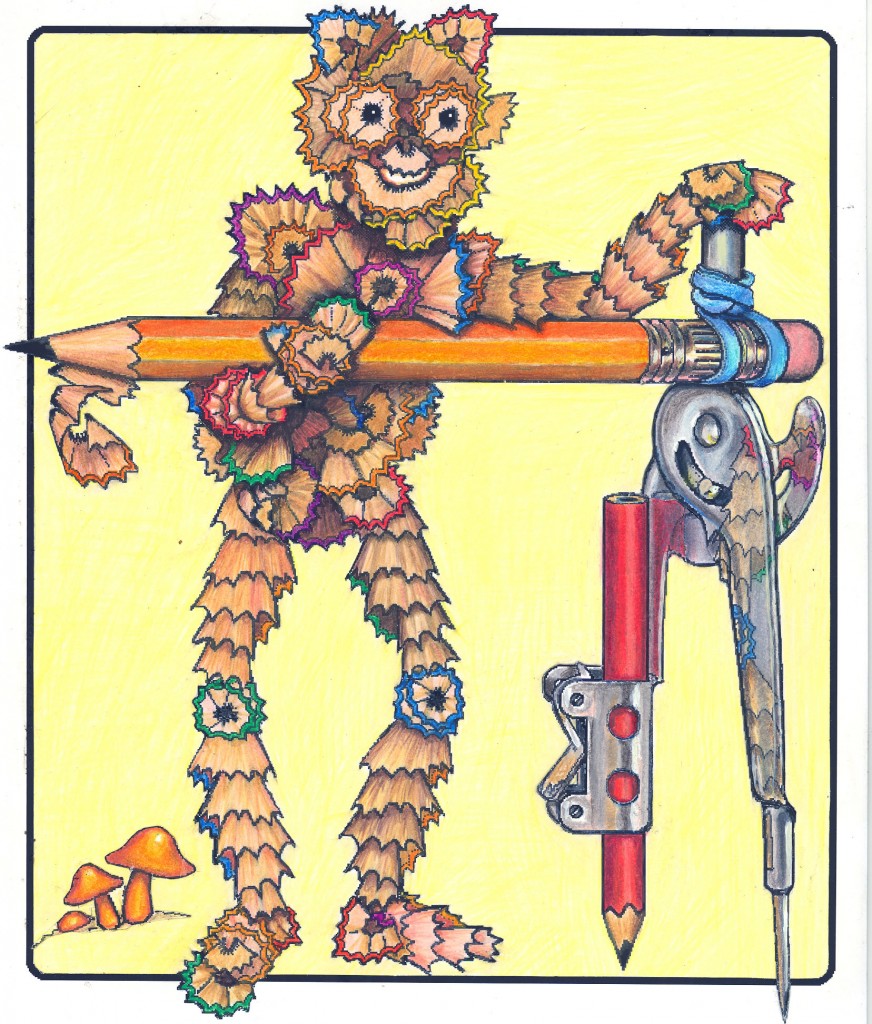

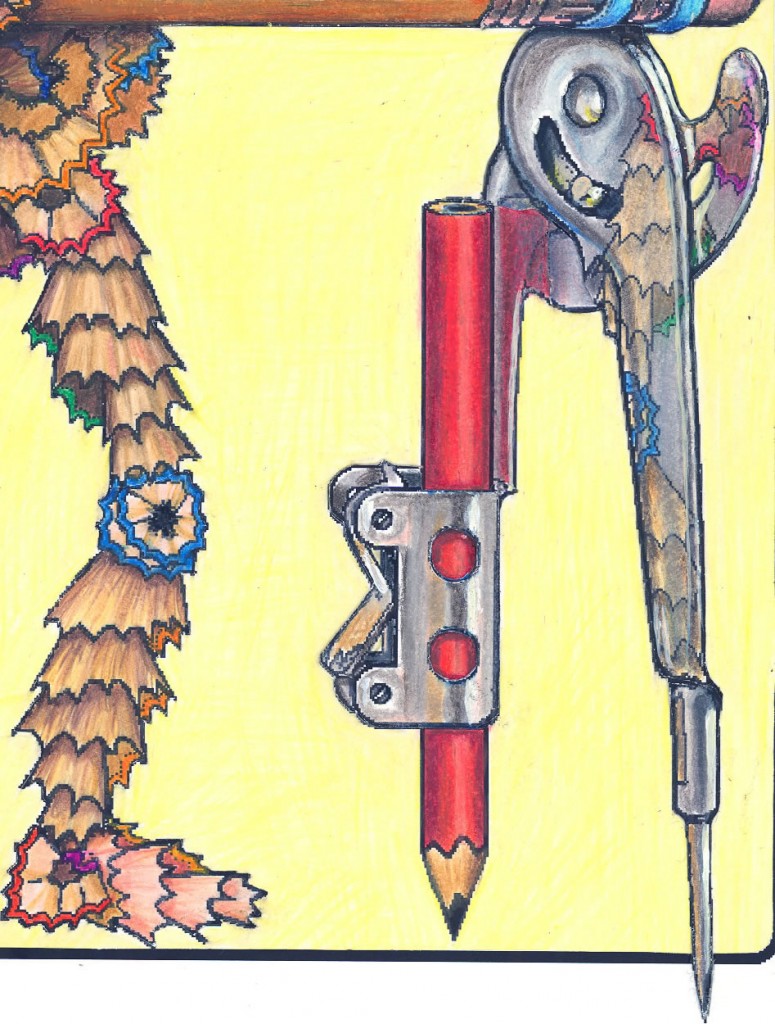

Mr. Pencil Shavings, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal (from ABBIE AND THE DESK DWELLERS)

… or from the imaginary?

Or you may want to paint images from your imagination. If so, you may want to learn to invent “models” from which you can create the imagined scene.

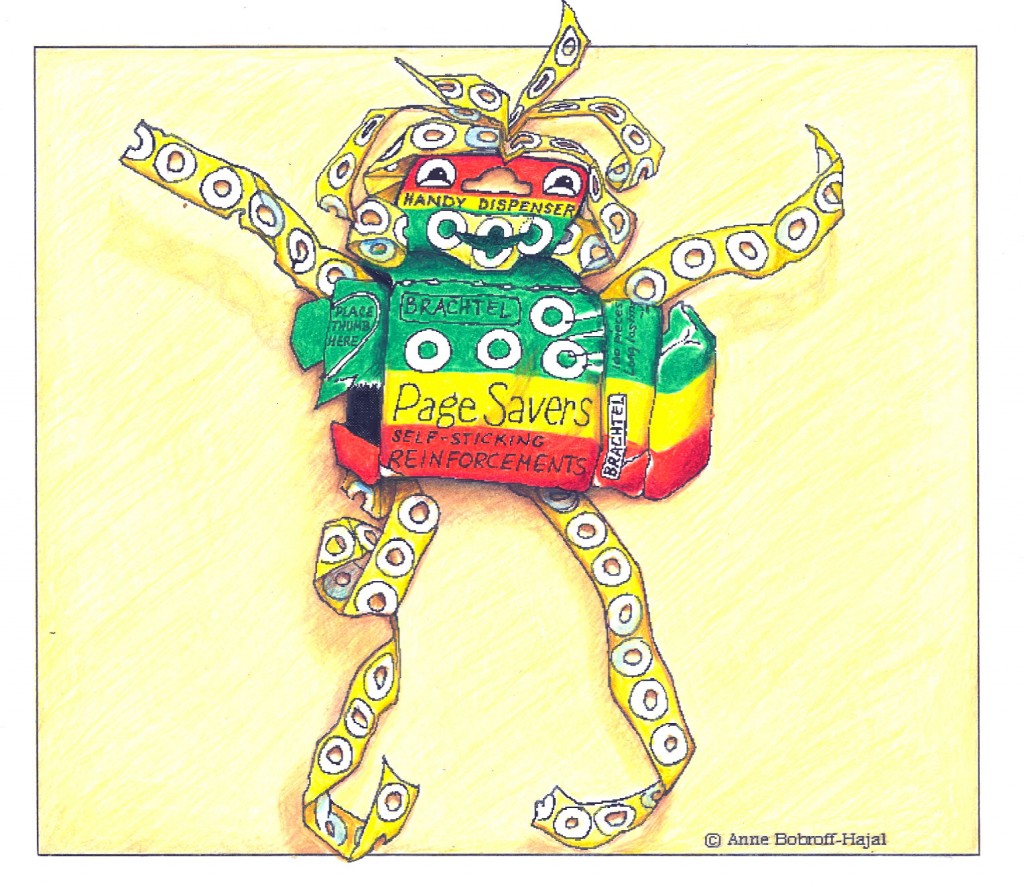

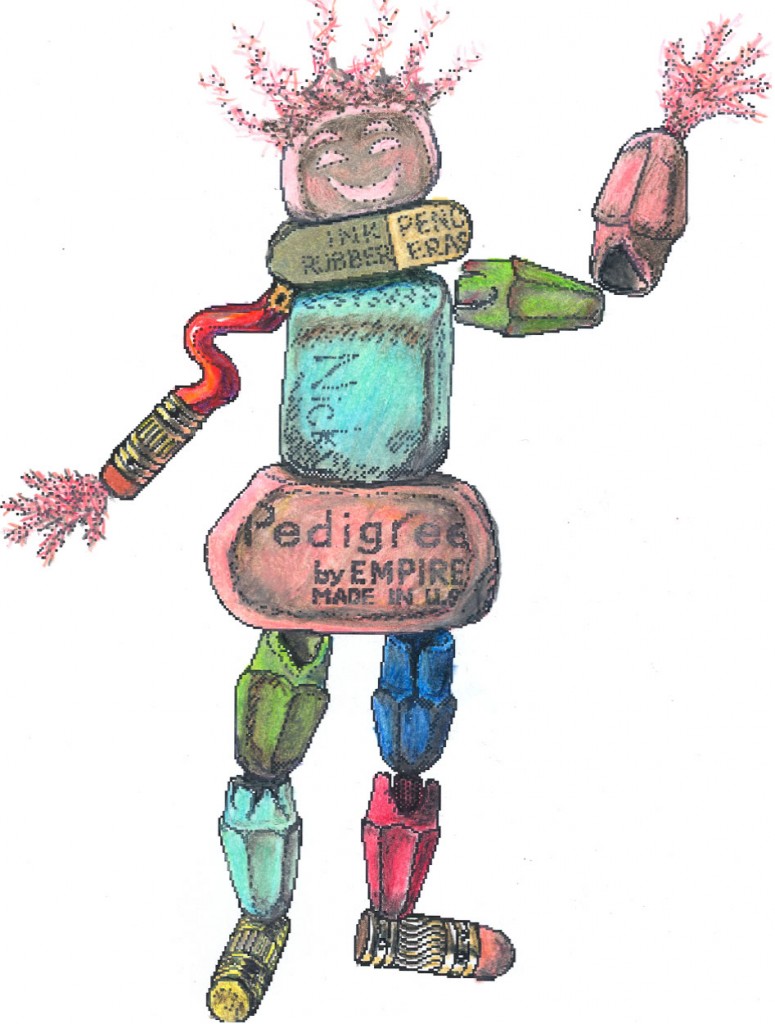

An example of this is animated character designs I created for a screenplay I wrote, called ABBIE AND THE DESK DWELLERS. These characters were made of detritus from kids’ school desks – pencil shavings; dirty broken crayons; gum and candy wrappers and scraps of paper; grungy old erasers and eraser dust.

How would you approach drawing these characters?

Here’s my technique, which you might have fun trying: I did things like grinding out pencil shavings using an old-fashioned pencil sharpener. Then I shaped the pencil shavings – or the worn crayon stubs or the battered erasers – as closely as I could to the character I imagined.

Slo Page Reinforcements, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal (from ABBIE AND THE DESK DWELLERS)

It can be hard because in the real world, things like shavings can’t hold their shape standing up as they can in your imagination. Yet to make the character look real, you need to draw the shavings (or whatever you’re using) from the proper angles even if in actuality they couldn’t hold those positions for more than a split second. So it involves a lot of adjusting the objects as you continue to draw.

Have you ever created models from real world materials to draw your own vision? If so, leave a comment about your method and how it worked. If not, give it a try! It’s challenging and fun to experiment with.

Reflective surfaces

Detail of reflections in protractor (from Anne Bobroff-Hajal's ABBIE AND THE DESK DWELLERS)

Notice the reflection of pencil shavings in the shiny metal of the protractor. What makes any reflective surface look real is that images of nearby objects appear on their surfaces – but not just anywhere.

I carefully set up a pencil shaving “leg” at the distance and angle from the protractor that my character’s leg was positioned.

Notice that the reflections appear in both the upright metal support of the protractor, and the curly metal extension that almost reaches the pencil eraser. Capturing that detail is what makes the protractor look real next to a little man made of pencil shavings.

You might enjoy practicing setting up some objects next to simple reflective surfaces. Look at them really carefully and try to replicate in your drawing exactly what you see.

Don’t bring in preconceived notions of what you think a reflection should look like – its color or shape. Any reflective shape – like the protractor’s – distorts the appearance of the object reflected in it. So just draw exactly the oddities you see, and you will find you’ve drawn a realistic-looking reflection in an object that looks three-dimensional.

But why bother with models? Why not just draw from memory?

Brenda Eraser Crumbs, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal (from ABBIE AND THE DESK DWELLERS)

Why bother with the hassle of setting up models? Don’t a lot of artists draw purely from memory? The answer is yes, many do.

For me, though, the everyday visual world is full of such surprises that I don’t want to just repeat from memory something I’ve drawn or seen in the past. Drawing from my memory of “what an X looks like,” by definition means I’ve developed a somewhat standardized way of seeing and drawing X. For me – and maybe for you – there’s nothing like the magical pleasure of discovering what’s unique about the particular “X” I’m drawing at that moment, and capturing that uniqueness on paper.

Reality is infinitely variable. If I hadn’t set up my shavings next to the protractor, for example, I might not have guessed that the reflection would appear in the very particular way it does over several surfaces of it. Scroll back up to the protractor closeup image above. Note how the reflection of the shavings continues down the point at the bottom of the protractor as simply a beige stripe. Notice also how the shading of the protractor itself – the grooves down its length, the white highlight at the top of its curve, the indentation around the grommet – all these intermingle with the shavings’ reflections. This interplay is what makes the protractor appear reflective and three-dimensional.

What if your subject is too large to set up a model?

I wish I had human models on retainer who I could call on at any time to dress up in the appropriate costumes and assume the emotions and positions I need to draw! I have a lot of books of models in hundreds of different positions, but I don’t recommend you spend much money on these books. It’s rare to find the exact position you need to simulate a particular activity you want to draw.

And the books don’t include the variations that come from the emotional intent of an action. Any action – say swinging an axe – shapes the human body differently if it’s taken, for example, in anger than if it’s taken in pleasure.

Before the web existed, I used to prowl libraries and magazines for photos that could serve as my models. The internet has provided a new wealth of relatively easily-found photos of people doing all kinds of activities, from shooting arrows on horseback to singing arias. Of course I’d prefer to draw from a three-dimensional reenactment. But I’ll never have a peasant chasing a soldier on horseback with a pitchfork in front of me – or an entire Mongol battle played out before me.

Next post, I’ll provide some tips on how to find images on the web that you can use as models for drawing scenes from your imagination.

Meanwhile, for Jonathan Linton’s popular video drawing demo and commentary, go here.

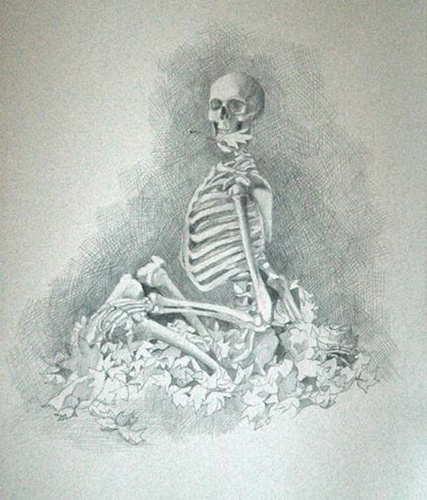

For a 2-part life drawing lesson, start Part 1 here.