This is part of a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. (The first, Introductory Study Guide is here).

In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

______________

Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV, 1530-84) is infamous for his brutal murders of thousands of his people during the second half of his reign. The most notorious of these killings were carried out publicly in grotesque ways, such as impaling or dousing the victim alternately with freezing and boiling water. Historians have debated whether Ivan was insane during the period he called the Oprichnina (1565-72), or was carrying out a strategy to eliminate encumbrances to his autocratic rule.

Question 1:

Was Ivan the Terrible crazy, or was he carrying out a rationally crafted policy?

I’d like to suggest a third possibility: that whether or not Ivan the Terrible was (at least at times) off his rocker, his murderous actions compeled a leap forward in the same direction as Muscovite rulers before and after him.

After all, even an unbalanced monarch grows up in a particular culture, with particular powerful people and groups around him, absorbing whatever history his mentors teach him about his country and government. Maybe even a mentally unstable ruler’s perceptions and extreme actions are so flavored by the world in which he lives that they move forward its trends even without his planning it.

Question 2:

Might a somewhat imbalanced ruler be able to continue – perhaps in a more ruthless way – trends begun by more stable rulers before him? How would this play out?

This question doesn’t necessarily have a clear answer, but it’s interesting to think about.

Why is thinking about Ivan the Terrible important?

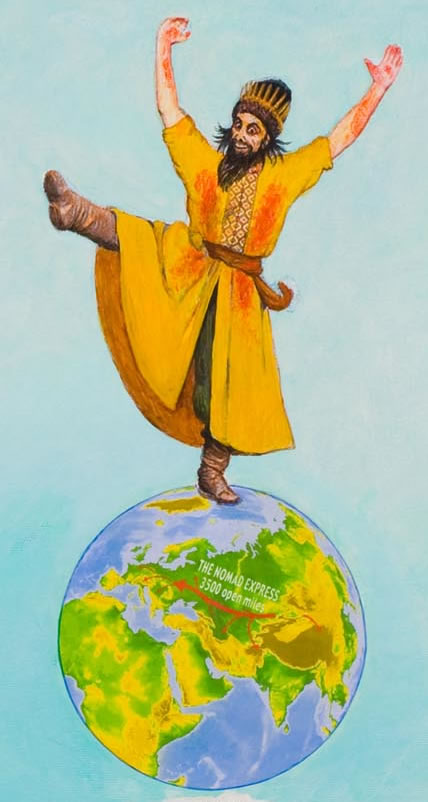

Ivan the Terrible as a fairy godfather giving his blessing to the infant Stalin (Modified detail from DRESS IT UP IN RESPLENDENT CLOTHES, painted by Anne Bobroff-Hajal)

Why should we bother our brains with questions about Ivan the Terrible anyway? Aren’t they only about some looney guy centuries ago in far-off, now-pretty-irrelevant Russia?

Well for one thing, many of Ivan the Terrible’s actions were strikingly similar to those of Josef Stalin 400 years later. In the 20th century, Stalin killed something on the order of 20 million Russians, most of them innocent of the charges against them, also in hideous ways. For example, both Ivan and Stalin executed some of their most devoted supporters. They each killed some of their best generals during or on the eve of major wars. And they each eventually turned the terror against the people who originally led it, executing many of those who had carried out its first phases.

So two Russian rulers who lived four centuries apart both committed similar horrific murders of vast numbers of their populations. Maybe they were both crazy!

But here again, whatever their mental status, their “crazy” behaviors were so strikingly similar that we have to wonder what was in the air in Russia – or the water, the land, or the vodka – that made two rulers almost half a millenium apart do the same maniacal things.

Question 3:

What might caused two rulers of Russia (USSR), living four centuries apart, to visit terror on their own populations in such similar ways?

Again, you won’t be able to respond to this question now. These “Big Questions” Study Guides – as well as my art about Russian history – chip away at these issues, providing ideas and evidence that students can mull over to arrive at their own opinions.

Where can you find a good summary of various historians’ views of whether Ivan was insane or had a goal and a strategy?

Detail of “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.s,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal: My representation of Ivan the Terrible’s face.

The two most recent books about Ivan the Terrible each provide excellent summaries of the lively ongoing debate about Ivan and his oprichnina by a number of historians in the US, Britain, and Russia. I recommend you read both to get two perspectives:

Isabel de Madariaga, Ivan the Terrible (2008), Forward, pp. x-xiv.

Andrei Pavlov and Maureen Perrie, Ivan the Terrible (Profiles in Power series, 2003), Introduction, pp. 1-6.

Two well-known American historians of Russia make the argument that Ivan IV was mentally ill during the oprichnina:

Robert O. Crummey, author of the superb The Formation of Muscovy 1304-1613, p. 162-72.

Richard Hellie, “What Happened? How Did He Get Away With It? Ivan Groznyi’s Paranoia and the Problem of Institutional Restraints,” Russian History 14 (1987): 199-224.

NOTE: Although I don’t personally agree with Crummey and Hellie on the issue of Ivan’s sanity, they have each written superb books, some of the very finest in the field of Russian history (Crummey’s The Formation of Muscovy and Hellie’s Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy; his research on slavery in Russia is also revelatory).

If Ivan’s murderous oprichnina had a rationale, what was it?

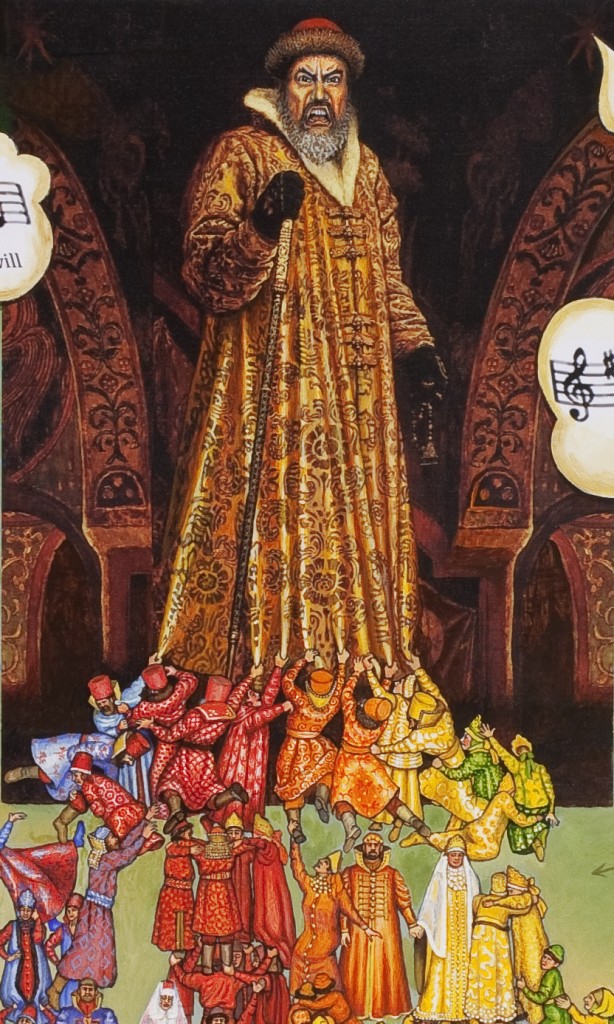

“Your Grasping, Scheming VIP’s,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 32″ x 66″

To decide whether Ivan’s actions were insane, we need to figure out whether there was any possible rationale to them. This doesn’t mean whether his actions were right or wrong (we can probably all agree they were morally heinous). It means we need to investigate whether Ivan himself may been pursuing a comprehensible strategy, however detestable we may find it.

Crummey has described the court in which Ivan the Terrible found himself as a young monarch who wanted the power to dictate without interference from anyone:

“The tsar lived within a spider’s web of family relationships. Ties of kinship or marriage linked many of the powerful court clans – princely and non-titled – to one another. These interlocking family groupings monopolized the highest commands in the army and filled almost all of the places in the Boyar Council [advisory council to the tsar]. Economically, their power rested on ownership of estates held on unconditional tenure. Any Muscovite ruler had to reckon with them when making appointments or charting national policy.” (Crummey, p. 160).

Text continued after next image

Russian tsars, including Ivan IV, didn’t like having to contend with the influence of the “web of clans” of the Russian nobility, portrayed in this detail of my “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.s”

Pavlov and Perrie paint a similar portrait of the obstacles the young Ivan wanted to overcome in his drive for power:

“…the boyars – and especially those of princely origin – retained great influence. The most eminent of the princes continued to own large family estates which were the remnants of their formerly independent principalities…. At court they comprised their own highly cohesive ‘corporations’ – the Suzdal’ princes, and Rostov princes, the Yaroslavl’ princes and the Obolensk princes among them. These corporations were formed on the basis not only of the princes’ common ancestry, but also on their possession of hereditary estates within their former principalities. Although their ownership of hereditary estates did not mean that the princes were independent landed magnates and opponents of centralization, it did imbue them with…influence at national level. Conscious of their high birth, the eminent princes laid claim to the role of the tsar’s closest counsellors. Such aristocratic pretensions on the part of the princely boyar elite could not fail to come into conflict with the autocratic aspirations of the first Russian tsar.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 124).

In other words, if Ivan was to become a true autocrat, he would have to cut his way free of the “spider’s web” of clans, whose power rested on their independent landholding.

How could Ivan cut through the “spider’s web” of princely clans?

The Russian historian Sergey Platonov, writing about Ivan the Terrible during the 1920’s,

“presented the oprichnina as a policy designed to weaken the old princely aristocracy by destroying its large hereditary landed estates and redistributing them on a conditional basis to the new class of small-scale military servitors.” Text continued after next image

Detail of my “Your Grasping, Scheming V.I.P.’s” shows the lower levels of the noble clans.

During the oprichnina (and afterward, according to Pavlov and Perrie, p. 169-203), Ivan killed or exiled to far distant lands many of the mighty old hereditary landowners. In their former court positions and on their former estates, said Platonov, Ivan instead installed lower-born servitors who had the right to hold the land only as long as they were in service to the tsar (called “service tenure”). This destroyed the power base of the old hereditary landowners, removing their ability to limit the tsar’s autonomy.

Platonov’s view was generally accepted for decades, until, as so often happens, it fell out of favor when later historians raised questions about it.

Later historians’ criticisms of Platonov’s work

For one thing, some historians* observed that many of the powerful old boyar and princely clans Ivan had exiled returned to court after the 7-year-long oprichnina (or according to Pavlov and Perrie, after Ivan IV’s death, p. 198), in their own turn ousting Ivan’s low-born courtiers. That sure made it seem that Ivan hadn’t intended to raise up those low-born courtiers after all. It seemed that life just returned to the pre-oprichnina status quo.

Janet Martin book cover

Other historians (e. g. Martin, p. 390 and Crummey p. 162-4) have argued that because Ivan was inconsistent in his choices of who to kill or exile and who to include in his oprichnina, he couldn’t have been pursuing a plan of social engineering. He exiled some princes and kept others at court, executed some of the low-born as well as some of the high.

“Over the course of the oprichnina’s existence, men of many backgrounds served in Ivan’s private army and court. Some came from aristocratic clans and many more from the lesser nobility. On occasion, some members of a prominent family served in the oprichnina, while others did not….

[Of those exiled to Kazan,] princes from the regions of Starodub, Iaroslavl and Rostov made up the largest single component…. [But] a significant number were not princes at all; a few came from distinguished non-titled families and considerably more from the lower echelons of the court.” (Crummey, p. 163-4)

Other historians have also stated that while the original oprichniki were of low birth, their composition later reverted back to the same old princes and boyars. (However, evidence for this point seems meager and appears to ignore Andrei Pavlov’s recent extensive research** on Ivan’s exiles/land transfers, including in the period after the oprichnina was formally over.)

Historians have also argued that a move by Ivan against the princes and boyars would have been purposeless, since all Russians, from the highest nobility to the lowest peasant, already agreed on the need for an autocratic tsar. No one, not even the princes, wanted a less centralized system.

Also, a semantic confusion seems to have crept into the debate. Some of the dissenting historians have considered that, by “raising up low-born courtiers,” Platonov adherents meant that Ivan’s new henchmen became a class aware of their own interests, with an independent power base from which to push for concessions from the tsar. These historians have accurately observed that in fact no new interest group or class arose. In fact, the Russian autocracy became stronger following Ivan’s reign, not weaker vis-a-vis the newly elevated servitors.

Also, a semantic confusion seems to have crept into the debate. Some of the dissenting historians have considered that, by “raising up low-born courtiers,” Platonov adherents meant that Ivan’s new henchmen became a class aware of their own interests, with an independent power base from which to push for concessions from the tsar. These historians have accurately observed that in fact no new interest group or class arose. In fact, the Russian autocracy became stronger following Ivan’s reign, not weaker vis-a-vis the newly elevated servitors.

“Both aristocrats (princes and boyars) and the service gentry accepted the unification of the land under the sole government of the Tsar, and the merging of service [land] tenure and allodial property…in which they all saw some advantages. Some Riurikid [the tsar’s lineage] princes who had survived in sufficiently strong clans might still hanker after their old appanage [independent land ownership] status, but the pervasive systems…acted as a barrier against any private initiatives,…and the monopoly of lucrative service drew the aristocracy and service gentry together” (Madariaga, p. 368)

* For example, Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980-1584 (2007), p. 392, and Madariaga Ivan the Terrible, pp. 182-3.

** Pavlov’s research articles unfortunately haven’t been translated from Russian, but they are described throughout Pavlov and Perrie book, Ivan the Terrible.

Can these viewpoints be reconciled?

It’s important for all students to read the sources themselves to form their own opinions. But having gone over the sources recently myself in preparation for creating my new artwork about Ivan the Terrible (in my primary role as an artist), I feel energized to present my own conclusions.

Pavlov & Perrie book cover

I believe most points of contention about Ivan the Terrible for which real evidence exists can be integrated into a single picture of the oprichnina.

First, let’s look at some historians’ point that, since all Russians already believed they needed a single, all-powerful tsar, Ivan would have had no need to bludgeon them into that belief. Well, as Crummy said (above), even people convinced of the need for a dictator may still battle with each other over access and influence. And battle among themselves the Russian nobility certainly did.

One might draw an analogy to children who know in their heart of hearts they need their parents to reign supreme. Yet they squabble endlessly to one-up their siblings and get their way. Ivan the Terrible was like the dad trying to drive the car while the kids kicked and punched each other in the back seat. He finally turned around and smacked them. Or maybe I should say: tortured and beheaded some of them to cow the others into docility.

(Remember I’m not saying this is a good thing or that the Russian people got what was coming to them. I’m only saying that Ivan didn’t like the fighting and interference, so he clobbered people to stop it.)

Now about those evictions…

Andrei Pavlov’s recent years of research in Russian archives have shown that criticisms of Platonov’s findings are on the one hand unfounded and on the other hand raise important nuances that need to be woven into our understanding of Ivan’s oprichnina.

To begin with, the monumental scale of evictions of magnates from their hereditary landholdings has now been confirmed by Pavlov’s research. “Over the entire period of the oprichnina,” he wrote, “the majority of Russian nobles may have been moved from their homelands…” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 142, my emphasis). Pavlov’s sources have also shown that removing many magnates from their huge estates enabled Ivan to reward his lower born minions with landholdings and money.

It is difficult to conceive of any other ruler in Europe having the power to force such massive migrations and land ownership transfers on his own population. Along with the terror Ivan visited on his people, this must have had a powerful impact on their way of life and their psyche.

… and the return of all those magnates to the tsar’s court…

Pavlov’s research confirms that, as asserted by recent anti-Platonov historians, many of the old princely and boyar families did return to the tsar’s court, some with promises they’d get their land back. However, Pavlov and Perrie found this return of the magnates did not occur until after Ivan IV’s death. They present evidence that even after the formal end of the oprichnina, Ivan continued the same oprichnina policies, relying ever more heavily on low-born henchmen (Pavlov and Perrie, pp. 169-200).

So does this mean that in the end the oprichnina had no effect, and therefore could have had no rational purpose?

Some historians’ vision that former magnates who survived the terror came back to court and went on with their lives just as before seems improbable. The returning magnates had lived through humiliation, impoverishment, torture, and terror. They may well have had a number of close family members and friends slaughtered, or have witnessed or certainly heard of Ivan’s ghoulish tortures and killings. Many former princes and courtiers were likely cowed into submission by this profoundly traumatic experience. As Chester Dunning wrote,

The resulting horror and dislocation traumatized the elite, seriously weakened many princely families, and increased the nobility’s dependence on the monarch (Russia’s First Civil War, p. 49).

In addition to the psychic impact, the princes and boyars had lost their power base: their hereditary estates. Pavlov and Perrie write that even in cases where magnates were told their land would be returned to them,

“it was very difficult in practice to implement this policy, which involved the large-scale expropriation of lands from their new oprichniki owners, and the allocation of other lands to the latter in their stead. In the context of the general devastation of the economy it was essentially unrealistic even to attempt this. As a consequence only a small proportion of the [displaced] nobles received their old estates back.” (p. 169)

The resettlement of the nobility “involved many problems and often led to their ruination and impoverishment…. [During the oprichnina,] land often passed repeatedly from one owner to another and fell into decline. Traditional farming methods were disrupted, and this had a dire effect on the peasants.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 143)

In short, while former magnates were allowed to return to high positions at court, many no longer owned the large, productive tracts of hereditary land which had been the source of their wealth and power before the oprichnina.

“Over the years of the oprichnina as a whole, the balance between hereditary and service lands, especially in the central regions of the country, shifted significantly in favour of service-tenure estates.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 143)

“The oprichnina badly damaged the family estates of the princely and boyar aristocracy, and it particularly harmed the hereditary landownership of the princes. The destruction of the boyars’ hereditary landholding and the loss of their previous links with the local nobility, led to a significant transformation of the Russian aristocracy, and made it completely dependent on the monarchy…. The sovereign’s court had previously had a territorial structure, with the most aristocratic and eminent nobles not only serving at court but at the same time heading their local associations of the nobility. By the beginning of the 1570s this had ceased to be the case, and the court had become organized on a new and more hierarchical basis. The privileged elite of the nobility, the Moscow ranks…had become detached from the great majority of nobles. They now…performed their service exclusively from the ‘Moscow list’ (based in the capital), which greatly increased their dependence on the state. This pattern of development of the sovereign’s court was to continue under Ivan Groznyi’s successors. As a result, the upper echelons of the nobility…were essentially turned into state officials, and as such they began to implement in the localities the harsh policies of the autocracy….” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 198-9).

Question 4:

Would it have been possible for Tsar Ivan to break up the landholding power-base of the old princes, boyars, and courtiers without using terror? Could he simply have peacefully decreed that the large hereditary estates were to be divided and distributed to a wider group of nobles?

Why did Ivan turn to the low born nobility to carry out his policies?

I suspect Ivan mounted his terror precisely because he knew the magnates would never give up their large landholdings peacefully. But how could he find people willing and able to carry out years of executions, tortures, and evictions across the country? He did it by turning to the impoverished bottom of the noble class and offering them rewards they could never have won before the oprichnina.

“Service in the oprichnina opened up for low-born nobles new opportunities for a successful career and to enhance the social standing of their clan. Sometimes oprichniki of humble birth, in defiance of the traditions of precedence* received higher service posts than more eminent…boyars and nobles. The latter, fearing the tsar’s disfavor, did not dare openly defend the honour of their clan, and had to accept their loss….” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 113; see also p.187)

*Precedence was the all-important key to high posts in Russia, and the source of most of the battles among them for status and influence.

The newly-elevated low-born, “being completely dependent on state service, and obliged to the tsar for their career and material welfare, …provided Ivan IV with a loyal and reliable base of support for implementing his political plans.” (Pavlov and Perrie, p. 113-14).

But as a number of recent anti-Platonov historians have pointed out, Ivan didn’t want to raise up the low-born nobles as a new upper class, conscious of their common interests and eager to press their demands on the tsar. Quite the opposite. Ivan’s goal was to destroy the ability of all classes to limit his own will.

What about Ivan’s inconsistency in attacking or rewarding the magnates vs the more lowly?

Historians such as Martin and Crummey accurately point out that Ivan was inconsistent in his rewards and punishments, sometimes exiling the lowborn and giving favors to princes. Crummey takes this inconsistency as one indication of Ivan’s insanity.

But I believe his point is answered by historians who have noted that the oprichnina strengthened the autocracy, not any one strata of the nobility. Ivan rewarded low-born nobles for a period of time in order to win their loyalty as his tools in his larger plan.

If Ivan wanted to assert his power over all levels of society, he couldn’t consistently reward any given category of people, or punish any other given category. His goal was not to create a new powerful class of favorites, but to undermine the security of all of them.

So Ivan had to be somewhat capricious. Only in this way could he make clear to every class of people that they had no independent safety outside his good will.

Question 5:

After reading some of the sources what is your own picture of Ivan the Terrible and the oprichnina? If you’d like to challenge any part of my reasoning – or if you’d like to agree – I’d love to hear from you in a comment or via email.

Final note:

You may have noticed that this entire discussion has been about different levels of nobility, not about those most subservient of all, the soon-to-be enserfed peasants. And of course, they were the real losers in all this. We’ll take up their lives more in later Study Guides.

Fun research question

Why, in my painting of Ivan the Terrible above, is he riding on a broom with a severed dog’s head on its front? Why did the real Ivan choose these symbols?

how does lyrica work lyrica garrett instagram lyrica cost cvs

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post. I will certainly comeback.

https://cheapestedpills.com/# best ed pill

lasix 10 – furosemide purchase lasix tablet online

Washer Pros of Austi – 603 Davis St #36, Austin, TX 78701, United States — (512) 352-9650

http://www.spb-center-remont-noutbukov.ru

Regards, Wonderful information!

sav-rx pharmacy a cvs pharmacy store is an example of a business benzodiazepines online pharmacy

https://cheapestedpills.shop/# natural ed remedies