You can find more about the images and ideas behind “Dress it Up” here. Closeups of each of its images in sequence are here.

Virtually everyone who sees “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes,” my new 7-foot triptych about Catherine the Great, asks me which parts are painted and which are digital. The answer to this question is as complicated as the finished triptych looks.

Anne Bobroff-Hajal: gallery talk about techniques used to create “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes,” partially visible in background.

So I’m going to use this post to describe my process, which involves a series of layers:

- First I paint the highly-detailed individual panels larger than they’ll be in the final triptych.

- Then I photograph what I’d painted and print it (on paper), combined with digital photos of e. g. the Russian Imperial symbol (the double-headed eagle).

- I paint on top of this print, then have it photographed and reprinted, and paint again on the print. I repeat this process as many times are needed to get the effect I want.

- Finally, I composite reduced-size versions of all these components into the final triptych and have it professionally printed on canvas.

- On the final triptych, I spend another month or two painting additional images and many adjustments on the canvas to balance the whole composition and get the effects I want.

“Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes” took over a year to complete.

Why did I develop this layered work process?

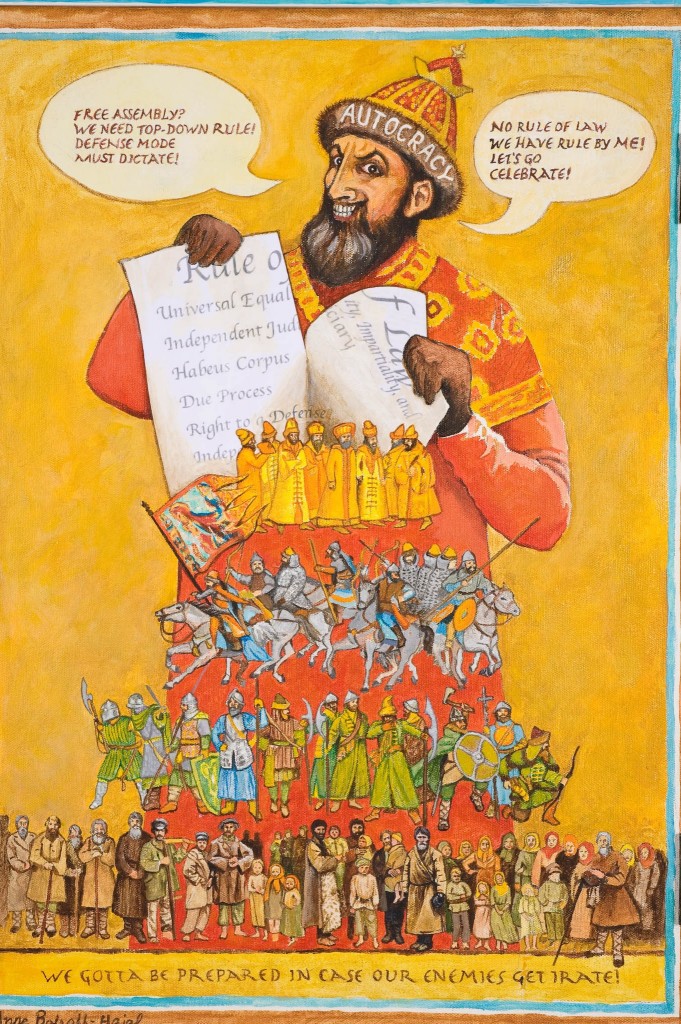

An experience I had while painting my previous PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS triptych moved me toward this process.

Detail of “Home Security at Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

In the detail (left) of that triptych, “Home Security at Any Crazy Price,” notice the row of peasants I painted along the bottom. As my “models” for these serfs, I had collected a lot of old, low resolution black and white photos of Russian peasants. I was in love with their sheepskin coats and bast sandals – but most of all with their profoundly expressive faces. I’d been looking forward to painting them.

But as it turned out, I was under time constraints preparing for an exhibit. And I realized that the tiny size of the peasants (the tallest was under 3 inches high) in this triptych was going to make it impossible to paint them in any detail.

The less-complicated peasants actually work better in “Home Security” than a more detailed version would have. The triptych was selected by curator Nan Rosenthal for her “Contemporary Confrontations” exhibit at the Katonah Art Museum and singled out in the NY Times review of the show.

Detail of line of peasants from “Home Security at Any Crazy Price,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal. The actual size of the tallest peasant painted is under 3 inches.

This made me wonder whether I should let go of my tendency to paint so precisely. A freer interpretation is sometimes better.

But then I kept thinking of those faces gazing out of the past.

Haunted by faces from the past

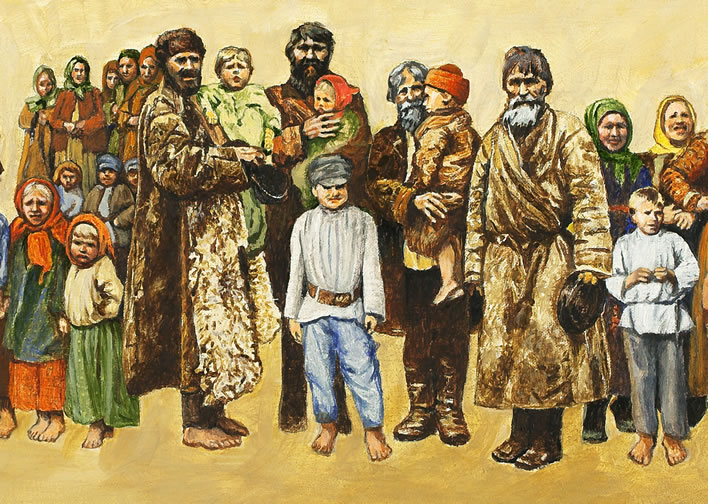

So once the exhibit was over, I decided to paint the same row of peasants again, this time larger so I’d be able to convey their expressions and the textures of their clothing more fully. I spent the next two months painting them (you can see and scroll over the entire row of peasants in the finished painting here.)

Three images demonstrate the difference size made. First is the detail above from the the row of peasants as they appear in “Home Security.”

Next is a detail of the same peasants as I painted them roughly twice as large.

Detail of “Still With You,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal. Actual painted size of tallest peasant is 6 inches.

Reduction of detailed peasants to size of those in “Home Security at Any Crazy Price” (small image with red background, above)

If I had then chosen to photograph and digitally reduce the larger painting to “Home Security” size, it would have looked like this (right). As you can see, this way of working generates a lot more detail in small images. It began to make me feel the possibilities of painting images larger and then reducing them digitally to fit into the final triptych.

Whether “looser” or more precise is better stylistically, I have to accept that as an artist, I’ll always tend to be attracted to finding ways to express more detail.

The influence of animation techniques on my process

Animation is created from hundreds or thousands of carefully-designed drawings passing in front of your eyes so quickly that they give the illusion of movement. Whether at 24 frames per second or 12, animation requires huge numbers of drawings.

In the days before computer animation (and probably still today to some extent), animation artists cut down on their nearly-impossible drawing work load by using bits and pieces of previous drawings. If Minnie Mouse’s hands moved from one moment to the next but the rest of her body didn’t, her body drawing could be reused and only the new hand position drawn. In the next few frames, if her leg moved but not her hands, the old hand drawings would be merged with the new foot drawings.

In addition, backgrounds were reused through many frames, with characters drawn moving in the foreground.

My involvement with and love for animation as an art form brought this influence to bear on “Dress It Up,” as you’ll see below.

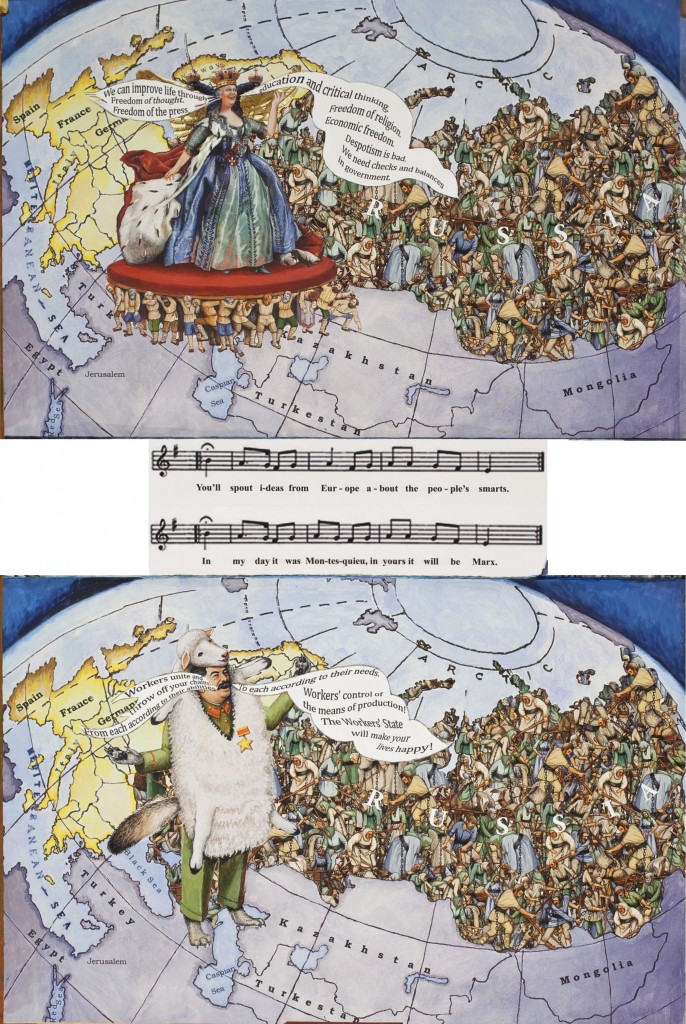

Catherine the Great and Stalin speechifying to the Russian people

The left panel of “Dress It Up” portrays Catherine and then Stalin each sucking up lofty ideas from Europe and spouting them out over the Russian people in billows. For Catherine, the European ideas were from the French Enlightenment; for Stalin they were Marxism (as the lyrics in the image describe).

The two images below are the final realization of what I saw in my imagination as I began working on visualizing this historical repetition. (For a close-up of all those peasants, scroll down to the last image of this post.)

How did I realize my vision?

Detail of left panel of “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal. Actual panel image is 18″ wide.

Map I created for left panel of “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes.” Actual width: 18″

I began by painting a roughly globe-like map focusing directly on Russia, with Europe visible around the curve of the earth. Finding a map like this turned out to be impossible: most maps aren’t centered on Russia. None have a peripheral Europe around the bend in the background.

So as my model, I ended up using my actual world globe placed in the position I wanted.

After painting it, I had it photographed so I’d have a digital image.

How could I portray a country full of peasants?

I pictured Catherine and Stalin speaking to untold numbers of peasants in Russia. How could I convey the effect of so many peasants?

First I imported my digitalized painted map into my computer. Then I began to experiment with various ways of using multiple copies of my paintings of peasants to fill the white “RUSSIA” space. But I just could not get what I wanted. I kept periodically coming back to this problem for almost an entire year, without success.

Finally, as I was playing with manipulating multiple, layered copies of another painting I had done of peasants (see below), I made one of those lucky mistakes – and suddenly had what I’d been struggling to find for so long.

Detail of “Serfdom,” upper left (round) panel of “Dress It Up in Resplendent Clothes,” by Anne Bobroff-Hajal. This was my painting which I manipulated digitally to fill “Russia” on the map for the lower left panel.

Map with digital images of my painted peasants composited in.

For a close-up look of the peasants in the map, scroll down to the last image of this post.

Why work digitally? Why not paint everything the old-fashioned way?

Why didn’t I just paint those peasants, you might ask? Why did I create this look digitally?

There are two reasons. One is that painting these serfs the first time – finding models for the scythers and other field workers, drawing and arranging them to fit into the composition, working out all those chains (each serf has a chain attached to a specific point at the bottom of the image), and then painting the whole thing – took a couple of months. Painting them all over again would have been prohibitive time-wise. If I’d spent time doing that, I couldn’t have created other parts of “Dress It Up.”

The second reason I worked with my painted serfs digitally is that it enabled me to play around limitlessly with layering of copies of my painting, fades, and color changes. This play is what eventually led me to the multi-layered look in the final triptych.

(Parenthetically, I do almost all the huge amount of planning for my triptychs in the computer. Integrating all the bits and pieces of my artwork into a coherent whole would probably be impossible without this.)

Next, Catherine and Stalin

Now that I had my map complete, I needed to create Catherine and Stalin as orators speaking words from Europe to the Russian people.

My process here was similar to classic animation procedure: I used a single background twice, with two different characters in the foreground. Again, the reason was the same as in animation: repainting this very complex background twice would have been prohibitive time-wise.

I had already designed my Catherine the Great character. Now I needed to create a Catherine who looked the same but airily orating. And she needed to face the opposite direction, toward Russia on my map and away from Europe. Both her head and her arms needed to be different.

I created my orating Catherine the same way an animator might. I began with my painted character. I had her photographed so I could manipulate her digitally in my computer. In Photoshop, I flipped her horizontally to make her face toward Russia and away from Europe. I had this version printed. Then I painted a new head and new arms on the print.

Upper left: my character design of Catherine the Great (head and wings are digital photos; I painted most of clothing and the serfs). Lower left: close up of character design face, taken from an actual portrait of Catherine the Great. Upper right: my 2nd version of Catherine, orating. Lower right: close up of face I painted, along with new arm.

Stalin as an orating wolf in sheep’s clothing, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

I created my orating Stalin as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. This design went through a number of iterations along the way as I debated how wolf-like Stalin’s body and posture should be, how he should be clothed, and whether his face would be human or wolf.

A larger image of this design can be seen in this post.

Last, the speech bubbles

The last element needed for my “spout ideas from Europe” panel was speech bubbles. In fact, the entire composition of map and orators was planned at every step to accommodate speech bubbles that would represent Catherine and Stalin sucking in ideas from Europe and spouting them out again over the Russian populace. (Catherine’s bubble sucked in from France; Stalin’s from Marx’s Germany.)

Below is one of my many, many planning images. In this one, I composited my pencil sketch of Stalin into my map and began to play with how I would shape and size the speech bubbles. I did this to check whether all of Stalin’s parts would fit properly into the map without blocking any crucial bits of it. I also needed to be sure that legibly phrase-filled bubbles could fit from Europe to Stalin’s mouth.

Planning image for Stalin’s speech bubbles, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

I approached the other panels of “Dress It Up” in the same way.

Completing the final triptych

Once all the images for “Dress It Up” were completed by this process, I reduced their sizes to fit into the 7-foot width of the triptych. I composited them and had them printed on canvas. I then spent roughly six weeks doing additional painting on top of the canvas. For example, I painted the large portrait of Catherine’s face in the center round top panel, replicating her historic portrait. I painted Stalin as a baby directly on this canvas – that character doesn’t exist anywhere except on the final triptych.