This post is part of “The World of Jews in Borisov/Barysaw,” in which I weave a tapestry of the lives of different members of the area’s Jewish community. Earlier posts about family members of those who have been in contact with me are here.

This is Part 2 of Finding Elkinds of Borisov/Barysaw. Part 1 is here.

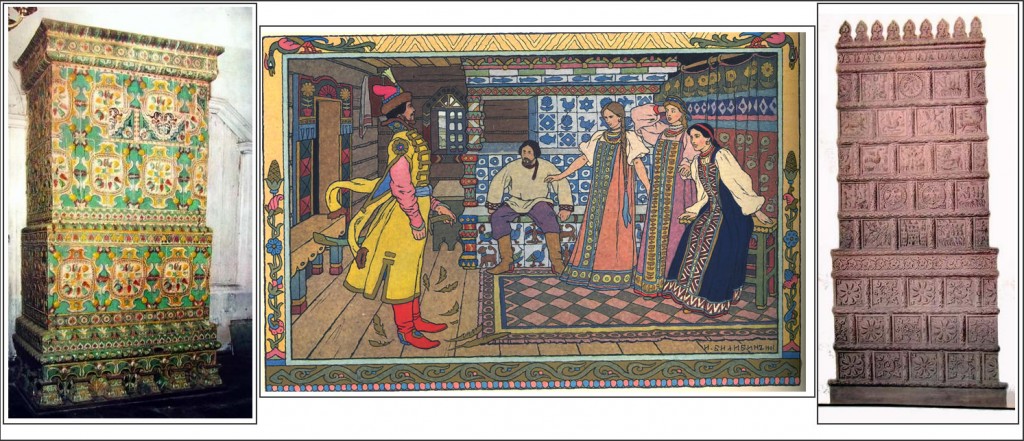

A spectacular example of a tile-covered Russian stove in the peasant style, with a space for sleeping on top, and steps to climb up there. See more about these tiles and stoves below.

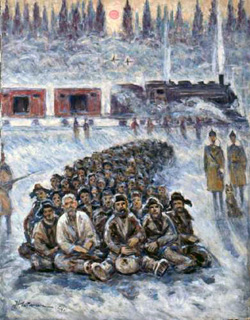

These two posts about Borisov Elkinds began when Logan Lockabey emailed me about his search for family members named Elkin or Elkind. In last week’s post, I wrote about a tragic chapter in Elkin/Elkind history: the deaths in Stalin’s Great Terror of five Borisov/Barysaw natives by those names.

This week, I promised a happier Elkind chapter, about information I found while researching for the first post. On an unofficial Russian-language Borisov City website, I had found short bios of seven additional Borisov Elkinds from the past.

These “new” Elkinds may or may not have been Logan’s family members. I haven’t had time to translate of all of their bios perfectly enough to post online (as I’ve said before, my Russian is good but not fast, since I use the dictionary a lot). I’ve passed along all these short life stories to Logan, in case any may be members of his family. I will update this post in future if he determines that.

Meanwhile, though, two Elkinds on this new list were intriguing to me.

Two Borisov entrepreneurs

Here are the brief bios from the Borisov website:

“ELKIND Nekhama Girshevna, entrepreneur. She owned one of Borisov’s pottery-tile enterprises, which opened in 1898.

“ELKIND Yudel, merchant. In 1883, he opened a tobacco manufactory, one of the first Borisov enterprises of the capitalist type.”

I was excited about these two Elkinds for a couple of reasons. The first is that they lived in Borisov at a time when my grandfather could have known them. My personal focus in most of these blog posts has been on the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before my grandfather, Boris L. Bobroff (Bobrov) emigrated to the United States. I’ve wanted to know more about the places he and his family lived, and about the people he might have known (or known of).

The second reason I was interested is that these two Elkind bios give information on the manufacturing enterprises that each created. I love discovering the kind of work people did in the towns I’m researching because it also tells us something about the nature of the town itself.

Not only do these little Elkind bios list the type of company run by each Elkind. If you read them closely, they also hint at a bit more: Borisov apparently had several pottery tile companies. And the tobacco manufactory which Yudel Elkind opened was “one of the first of the capitalist type” in Borisov in 1883.

Yudel Elkind and tobacco manufactory

So far, I’ve had little luck finding information about tobacco manufacturing in late 19th-century Russia. So for the time being, I can’t explore Yudel Elkind’s work. The one bit of tangential imagery I have is 1907 photos of two match factories in Borisov. You can see the Victoria Match Factory here, and the Berezina Factory (left).

These photos give a feeling of the factories beginning to develop in Borisov/Barysaw around the turn of the century. We can only wonder for now whether Yudel Elkind’s tobacco “manufactory,” opened about 25 years before these match factory photos were taken, resembled them in any way.

It’s conceivable that Elkind’s tobacco manufactory, described as “one of the first Borisov enterprises of the capitalist type,” may have been fairly large. The word “manufactory” (in English and Russian) suggests some kind of production-line process done by hand, without machinery. But it can also be an archaic word for “factory.” What kind of machinery might Elkin’s manufactory have involved, if any?

I believe that figuring out what the next questions are is the first stage in good research. That means we’re making progress!

Nekhama Girshevna Elkind and the pottery-tile business

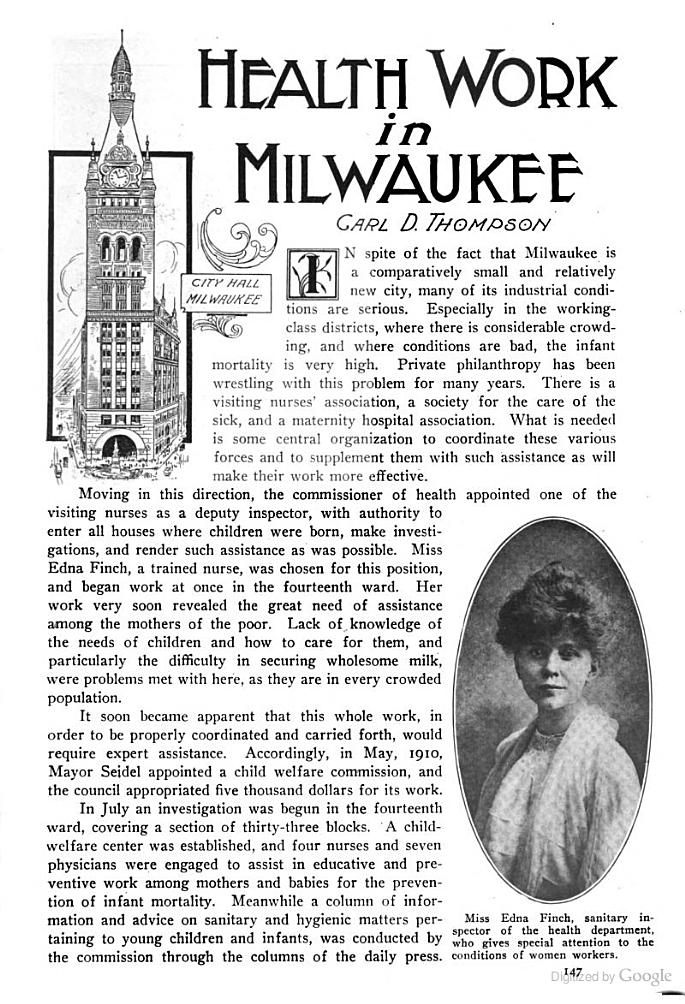

I would love to know the story of Nekhama Girshevna Elkind herself, because she must have been a very enterprising and clever woman. Since I don’t have her specific life history, I turned to researching the type of work she did. And here I discovered something interesting: there were a lot of Belorussian Jews in the pottery-tile business at the end of the 19th century. So it seems that Nekhama was in good company with her business. She had other similar examples in her area, and maybe some solid competition.

According to the 1904 Collection of Materials about the Economic Position of Jews in Russia (Сборник матеріалов об економическом положенiи евреев в россiи), several places in Belarus had “favorable soil characteristics, conducive to the rise of the pottery and tile business.” There were abundant clay deposits not far from the surface, along with plenty of the fuel needed for firing pottery. And everyone needed to buy dishes and tiles. So Nekhama Elkind had a guaranteed market.

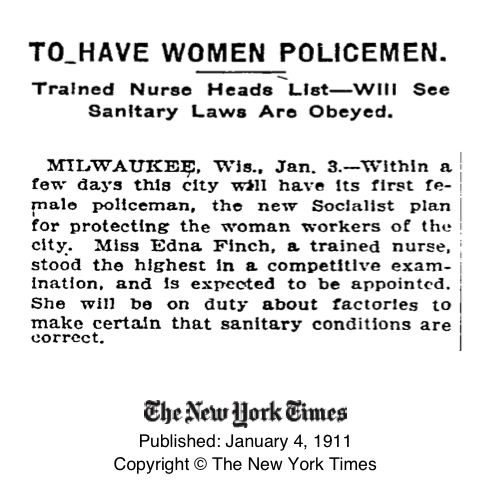

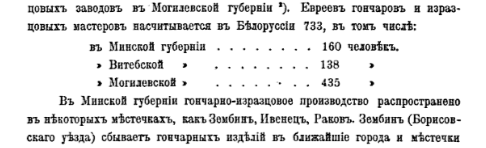

Snippet from Collection of Materials about the Economic Position of Jews in Russia, 1904. Gives the number of Jewish potters and tile masters in Minsk, Vitebsk, and Mogilev guberniyas (alphabet written in the pre-revolutionary style).

Borisov uyezd’s neighbor, Mogilev province, had the hottest hotbed of Jewish tile and pottery makers. By 1909, there were 415 Jewish pottery and tile makers there, and 14 tile plants. The tiles they produced were sold in all cities of Mogilev, and in Kiev and Kremenchug in the Ukraine.

The famous green-glazed tiles (muravniye). "Green tiles from Ivenets may be seen very often in homes in surrounding cities and towns." (left)

Nekhama Elkind’s neck of the woods: Borisov in Minsk province

Minsk guberniya, where Borisov is located, came in second to Mogilev, according to this source. Of 733 Belorussian Jews involved in making pottery and tile, 160 lived in Minsk guberniya (province).

“The town of Zembin (in Borisov uyezd) sells its wares in nearby cities and small towns at a yearly sum of 2,000 rubles. In the small town of Ivenets (Minsk uyezd), traveling merchants yearly buy 5,000 rubles worth of earthenware dishes and tiles from the makers. Green tiles from Ivenets may be seen very often in homes in surrounding cities and towns.

“In Rakov…there are about 25 pottery workshops. Of them 6 are Jewish…. The quality of the work of Jews and Christians is equivalent: it is possible that that of the Jewish masters is even higher since they depend entirely on this trade, while among the [Christian] peasants, it is only a secondary trade to their agricultural work.”

Borisov (here "Barysau") is in the bottom right corner of the map. The red star marks Zembin in the center.

The city of Borisov isn’t mentioned here. So we might wonder whether Nekhama Elkind’s tile enterprise, along with the others referred to her bio, were actually in the town of Zembin in Borisov uyezd, rather than in the city of Borisov/Barysaw, 14 miles southeast of Zembin (see map, right).

How large was Nekhama’s workshop?

The Economic Position of Jews in Russia says that the average size of ceramic shops in Belorussia was two people, generally a master and an apprentice. So Nekhama Elkind’s tile shop was likely small. Was she only the owner of the shop, or did she create the tiles herself? For now, I can’t answer this question. But I did find descriptions of the process of creating the tiles, the method that Nekhama Elkind’s workshop undoubtedbly used.

How did Nekhama Elkind create her tiles?

A Russian English-language website describes the process, and I like to try to envision Nekhama going through each step – or maybe directing as some one else did it. Can you picture her in the description below?

When starting to make a tile,

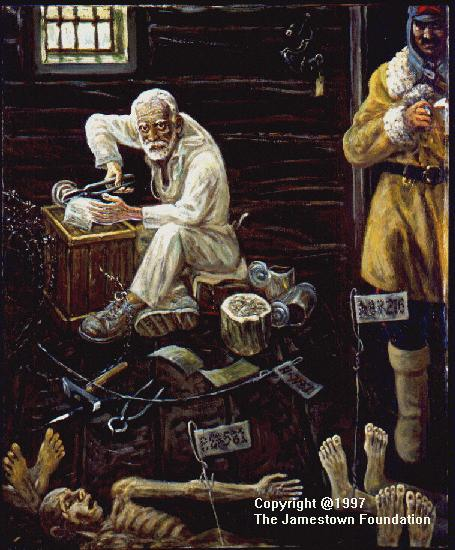

“the potter would temper clay with his hands, his fingers penetrating inside the clay and removing small pebbles and clots, anything that could lead to cracks during baking. The clay took in the warmth of the master’s hands and became pliable. Then the master would fill it into a wooden mould with a carved ornamentation on the bottom.

This carved design inside the mold created a relief design such as the birds on the blue tile above and the two tiles left. The bottom of the mold was first “sanded” to prevent the clay from sticking.

Then the potter

“consolidated it and pressed into the tracery holes. After processing it on the potter’s wheel he dried it and baked in a furnace. The pattern was not always relief. Sometimes the front side of the box [that is, the part of the tile that showed in the finished tiled object] was smooth and painted.”

Last, the decoration, whether relief or painted, was glazed or enameled.

As this description suggests, the earliest Russian tiles, beginning in the 15th and 16th centuries were decorated with relief designs. By the 18th century, the front of tiles was often left flat and painted with elaborate designs (see photo below).

What was Nekhama Elkind’s market for her tiles?

We can all imagine how large the market for pottery dishes must have been in Russia, since everyone needs dishes. But what about tiles? Why were they in such wide demand?

Tiles were used in Russia to decorate lavish interior and exterior walls. The most famous example of tile decoration on the outside of a building is undoubtedly St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow.

But the real reason there was such a market for tiles in Russia was the Russian stove, which was used for heating and sometimes also for cooking and sleeping (see photo at top of this post).

Why did the Russian style of stove create such a huge market for pottery tiles?

Russian stoves were big, with a vast surface area. Covering them with tiles meant buying a lot of tiles.

I don’t think that the average peasant stove was sheathed in tiles. But anyone who could afford them wanted them, for their beauty and practicality. Tiles added to the stove’s heat transfer capacity. And they were much easier to clean than earthen surfaces.

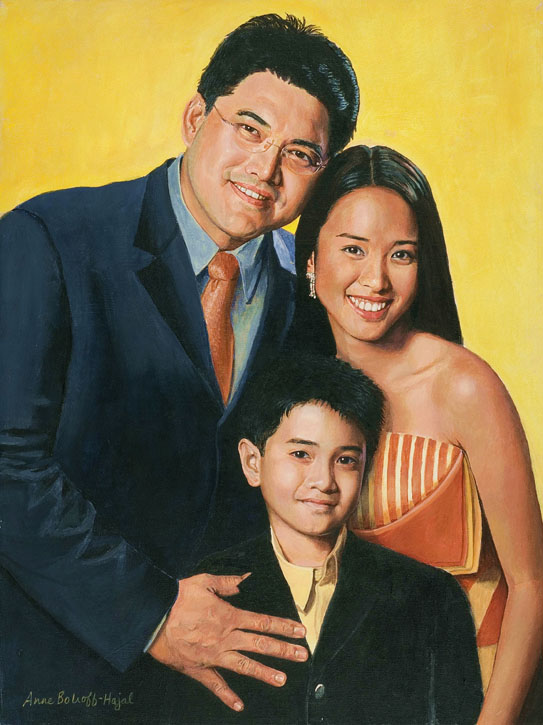

Tile-covered Russian stove from the Rostov Prince's Palace. Note many of these tiles are the flat-surfaced, painted style.

Why did the Russians have gigantic stoves that required so many tiles to decorate, creating a great market for Nekhama’s wares? I’ve always wondered what was going on inside all that bulk that would make Russians want to sacrifice so much of their living space to them.

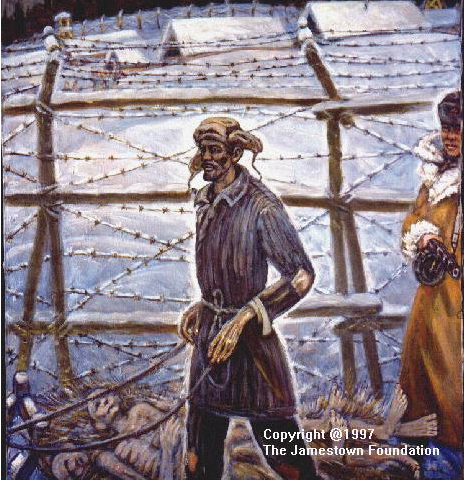

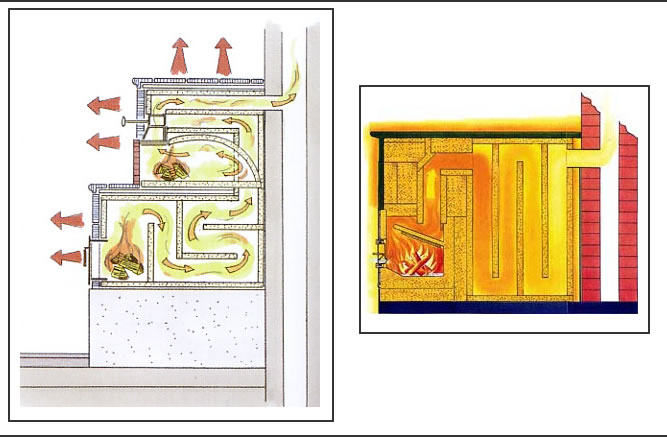

A fascinating article in Low Tech Magazine explains that inside Russian stoves were labyrinths of smoke channels (see diagram below). These channels held onto the heat, allowing it to be absorbed into the masonry rather than escaping up a chimney. They also allowed more complete combustion of the fuel, unlike the partial combustion of our fireplaces, which coat the chimney with half-burned fuel (creosote). Over many hours, the Russian stove’s masonry and tiles slowly radiated their heat (they didn’t use convection, as most of our heating systems do in the US).

Interior diagrams of Russian stoves. The one on the left appears to be a more vertical stove, while the one on the right seems to be the more horizontal peasant style.

These stoves were incredibly efficient at heating homes through frigid Russian winters – much more efficient and non-polluting than the American hearth or iron stove. Properly operated, a Russian stove heats 60 square meters for an entire season using a single tree. (If you’re interested in more on these stoves, along with many gorgeous photos, read the Low Tech article here.)

Did Nekhama sell her tiles only to the wealthy, or was her market broader?

All Russians, from the poorest peasants to tsars, heated their homes with these huge stoves. But did the average Russian’s stove have a layer of tiles? Was Nekhama Elkind likely selling her tiles only to the wealthy, or could her market have been wider?

According to one source,

“In the nineteenth century, tile production became widespread. Products were manufactured in a wide assortment, varying in cost and artistic value for a broad section of consumers. Tiles were designed primarily for finishing stoves, perhaps the primary and indispensible part of Russian life.”

Well, this general statement doesn’t answer the question fully. I’ll be on the lookout for more information on Nekhama Elkind’s tile customers in future. Meanwhile, though, it seems clear that the frigid Russian winters, and the stoves designed to cope with them, likely created her market. And the rich, accessible clay deposits of Borisov uyezd gave her the raw materials to meet that market.

I’ll end this post with some additional images of exquisite Russian tiled stoves.

Before I do, though, I’d like to take a moment to dedicate this post to a dear friend, Saul Scheidlinger, who died this past week, and to his wife, Rosalyn Tauber-Scheidlinger. Saul was a psychologist who made great contributions to the field of child and adolescent group psychotherapy. He was appreciated worldwide for his wisdom and as a great teacher and trainer. He was a cultured and lovely man, who, with extraordinary grace, overcame profound tragedies earlier in his life. I miss him. And I think he would have enjoyed these images of artistic Russian stoves.