Why do our brains withhold from our conscious grasp a way of seeing that’s so useful? Why aren’t we able to easily dip into that mode of seeing when we want it to draw?

When I posted a two-part online drawing lesson a couple of months ago, I received a response that got me wondering.

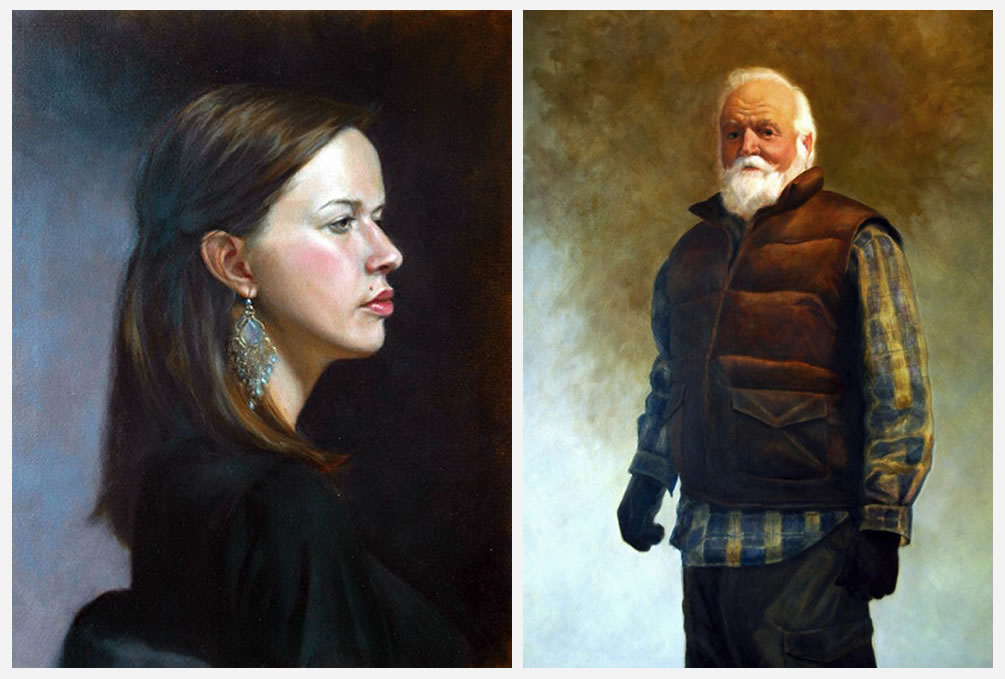

The response was from a wonderful young Lebanese artist, Vanessa Gemayel. Vanessa paints luminously about today’s destruction of the beautiful traditional architecture that gave Beirut its unique atmosphere, replaced by generic modern architecture that is sadly making Beirut look like every other city in the world.

Vanessa, after trying out my figure-drawing lessons, wrote to me that she found them “very cool and helpful.” But, she added, “you make it seem a lot easier than it actually is.” And of course Vanessa is saying outright what many people feel about drawing instruction.

That got me wondering what in the human brain makes drawing from life so not-easy to learn.

All jobs involve a learning curve, often long and hard to get through. Drawing from life is in that sense no different from any other expertise. Many skills, for example, require years of study before mastering them. Others need endless practice.

I believe that the most important element of learning to draw, though, is an “aha moment” – or maybe a small series of such moments. In those few moments, you suddenly start being able to see in a different way which enables you to draw realistically. This alternate way of seeing is for me, and for many who draw, the single most basic and important tool we use.

True, endless practice must follow the aha. But the practice isn’t what blocks most people who really want to learn to draw.

In learning to draw, I think what is elusive to many people is the “aha moment” when they begin to see in that all-important alternate way.

With that aha, you will be able to learn to draw easily.

What is the aha moment in learning to draw?

In my drawing-lesson posts, “Learning to Draw by Playing the Angle Abstraction Game,” I called the technique of seeing differently “angle abstraction.” The artist is able to see what they’re drawing as a series of angles and shapes that are much easier to draw than when their subject is seen “normally.”

Other artists have given other names to their alternate way of seeing. Betty Edwards has written two groundbreaking books in which she calls it “right-brain mode,” or “R-mode” (as distinct from left-brain mode, or L-mode).

L-mode is how we consciously think in our everyday lives. It’s language-based.

R-mode – the one that enables us to draw – is non-verbal and does its work mostly outside our conscious awareness.

The “aha moment” happens when you are suddenly able to consciously access and use R-mode to see differently and draw.

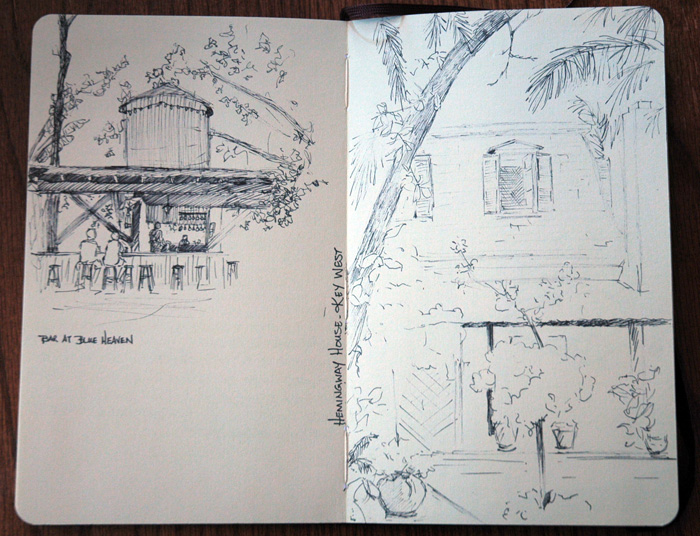

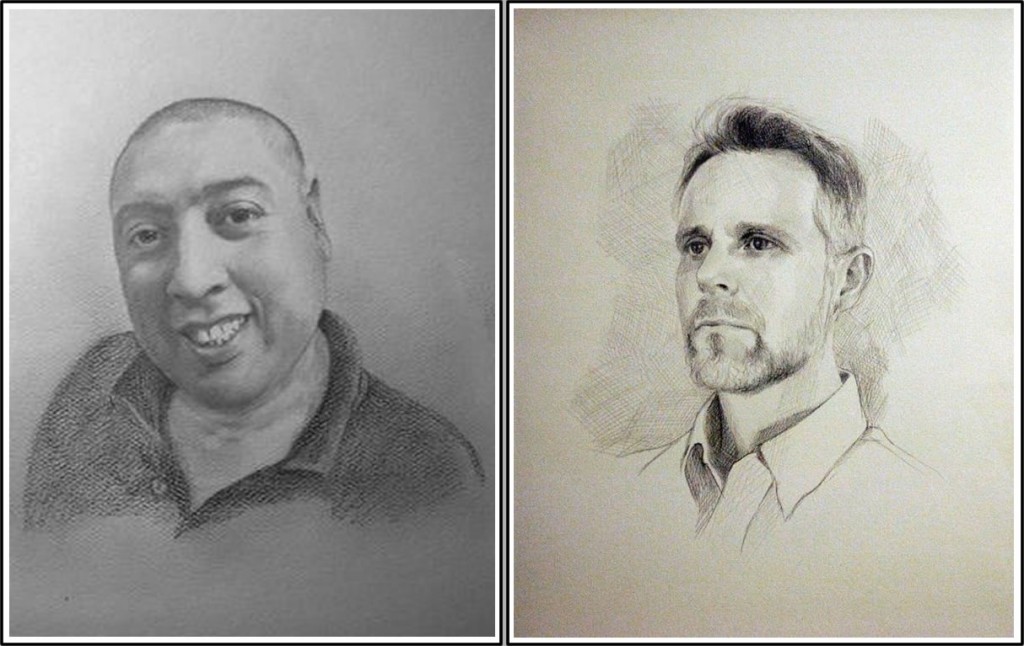

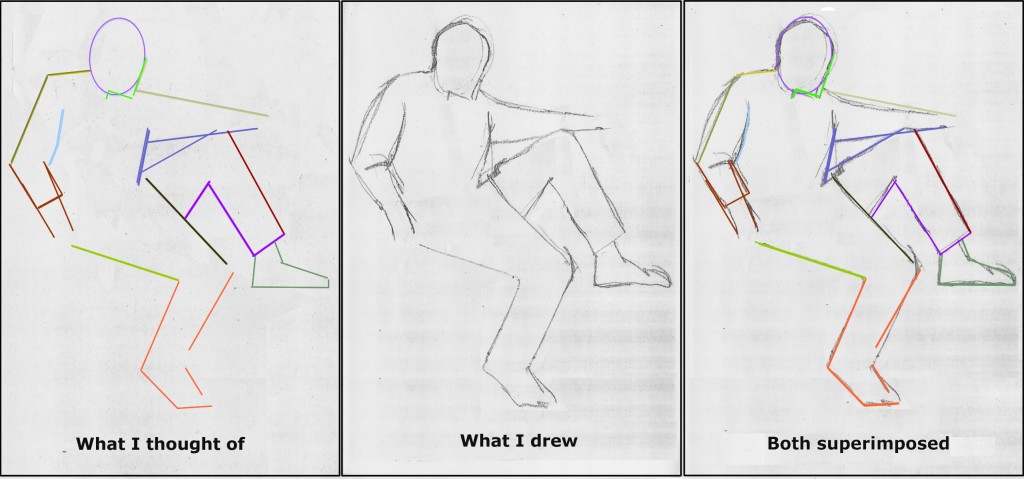

One frame from my free online drawing lesson, "Learning to Draw by Playing the Angle Abstraction Game"

But why would our brains withhold from our conscious grasp a way of seeing that can be so useful? Why shouldn’t we all be able to easily dip into that mode of thinking when we want it to draw?

Why do our brains block our aha moments?

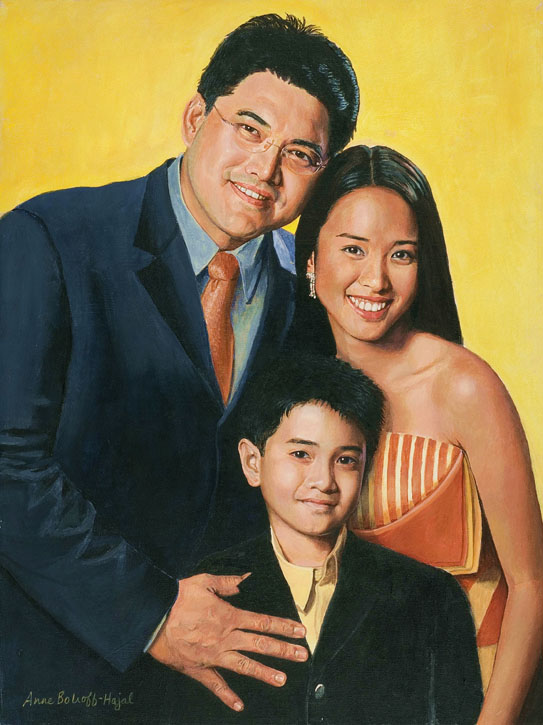

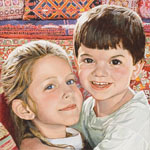

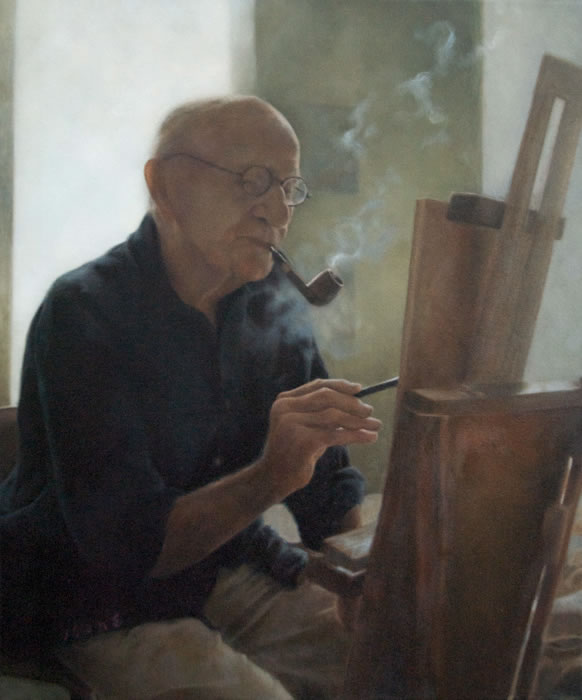

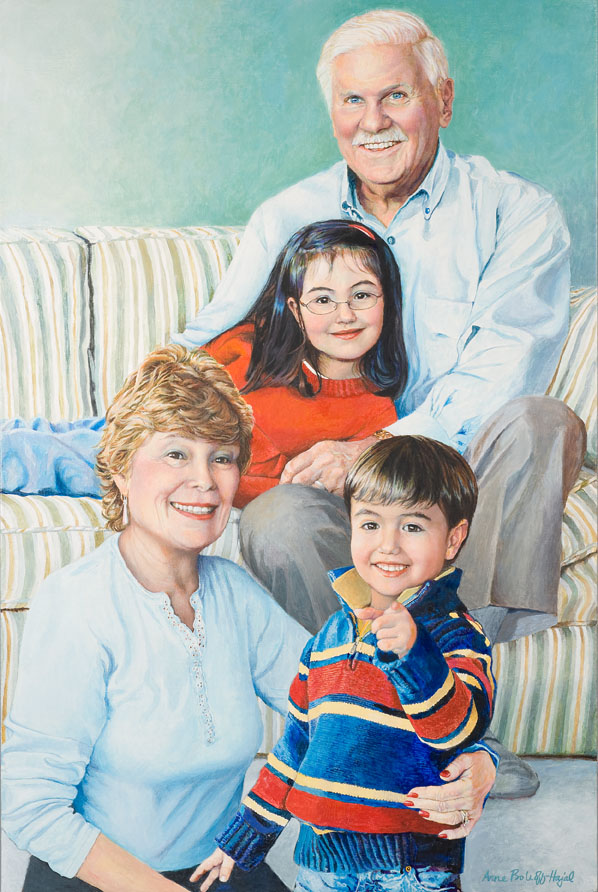

Portrait of the Steinbergs, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal. Notice how different each of the hands looks.

I was pondering this question when I recently ran into a wonderful answer in one of Betty Edwards’ books, Drawing on the Artist Within (p. 208).

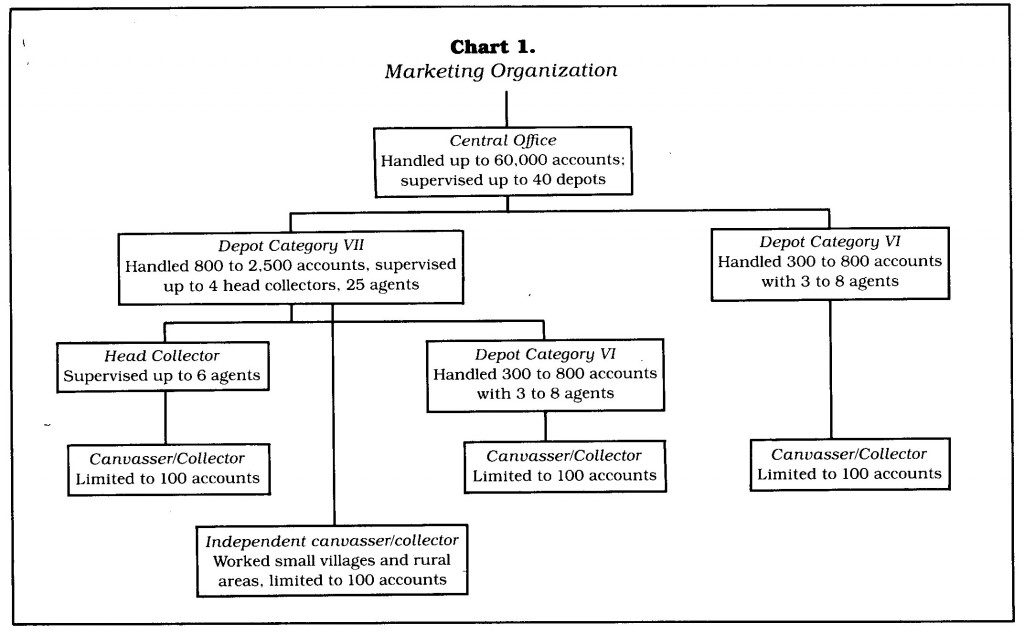

One way of conveying Edwards’ explanation here is through a group portrait I painted (right) of Bob and Gail Steinberg with their grandchildren, Riley and Alex. This portrait illustrates one of the classic problems of drawing: how to draw parts of the human body when they are foreshortened – that is when they are coming straight at us, so they look very different from what we usually think of as an arm, a leg, a hand.

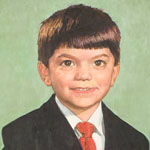

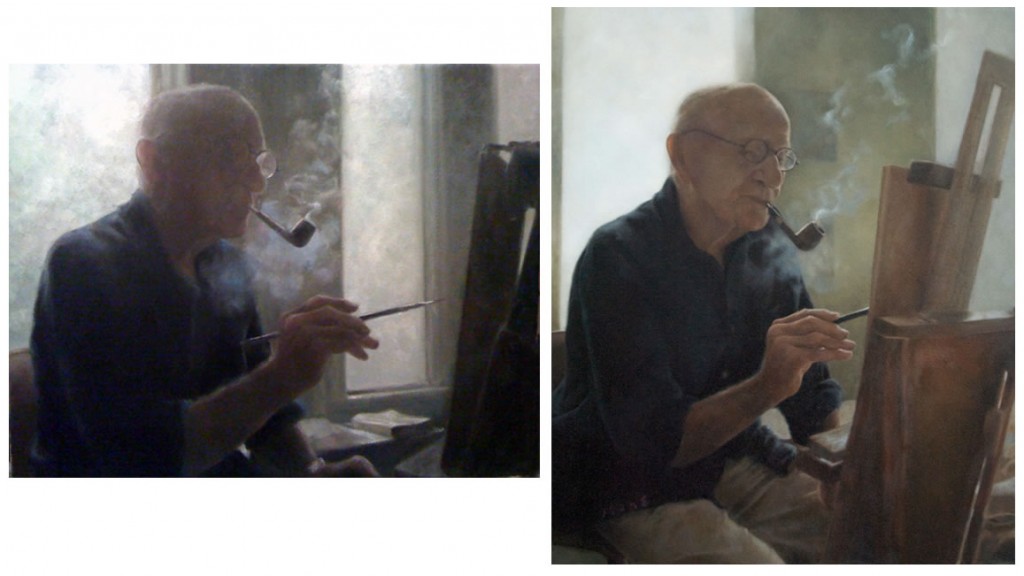

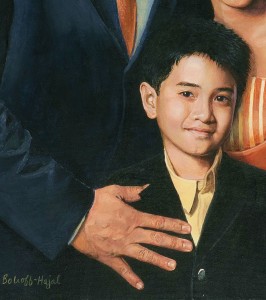

The most obvious foreshortened body part in this portrait is the hand of the Steinbergs’ grandson Alex, who is pointing directly at the viewer. Everyone who sees this painting knows exactly what that hand is doing. But in fact, it bears little resemblance to our standard concept of what a hand looks like. Our conscious, rational L-mode brain typically thinks of a hand as something more like the father’s hand in another portrait (below).

Detail of Edwin Ermita and Two of His Children, by Anne Bobroff-Hajal

That little pointing finger

Alex’s pointing finger appears on the canvas as a small circle, not the long tube shape we associate with fingers. That’s strange enough. But beyond that, the thumb seems bigger than the other fingers. And it stretches out at an angle that we rarely think of thumbs taking on. That thumb seemed so odd to me while I was painting it that I rechecked it multiple times to be sure I had it right.

In fact, it’s exactly because I allowed each finger to take on its actual shape – rather than what I might have consciously thought it should look like – that makes it possible for everyone who looks at the painting to know exactly what that strange conglomeration of flesh-colored blobs is.

Now for the other hands….

In addition to the little pointing finger, we can look at the other hands in the Steinberg portrait. When we really study them, none of them is shaped like our standard concept of a hand.

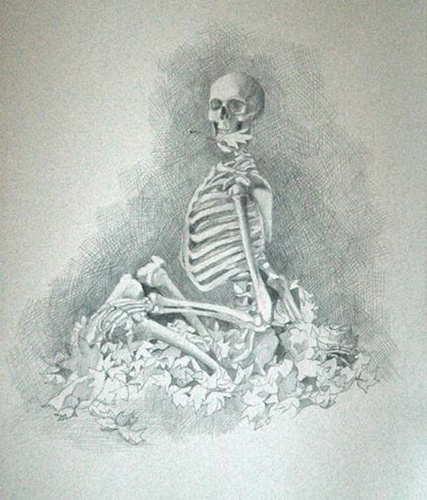

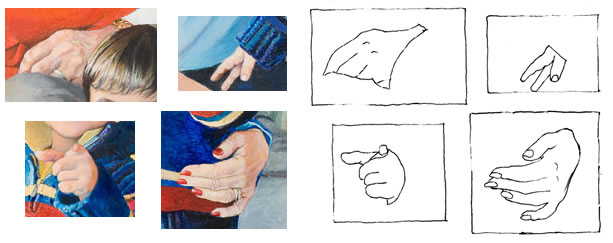

Detail of Steinberg portrait hands, along with black ink outline of each

Bob Steinberg’s hand appears almost triangular, with only parts of four fingers visible.

Little Alex’s right hand is visible as only a thumb and two fingers. And the index finger looks like it’s separated from the thumb by an interloping finger which in reality is farther away from the thumb.

Gail Steinberg’s fingers conform fairly well to our standard image of a hand. But what about the back of the palm area? It looks much smaller and less rectangular than it “should.”

It’s fine for us to view these shapes as being all different when we’re drawing. But it’s also crucial for our daily functioning that we recognize all of them as the same – as hands. It’s the job of our efficient, everyday L-mode, says Edwards, to quickly classify all these odd shapes under the general verbal rubric of “hand.” And that verbal rubric is envisioned as in Edwin Ermita’s hand above, stretched flat, with five fingers roughly the same length as the palm.

If our brains had to go through a conscious, verbal process of debating whether each of a group of very dissimilar objects is or is not a hand from a different angle, we’d never get through our day. We’d be mired in endless debating: “I see three of what look like fingers, two from the side and the third, a thumb, from more of a straight-on view. But if they are fingers, why aren’t there five of them, and why aren’t they attached to a hand? Is the hand out of my sight, or ….”

Our unconscious interpreter

It’s R-mode, says Edwards, that takes in all the differences in shape and size, and, with lightning speed, calculates from them where things are in space, what they are, and so on. R-mode sees, for example, that the back of Gail Steinberg’s hand appears to be getting smaller not because it is smaller, but because it’s receding back from her fingers, curving around Alex’s body. “It’s a hand, all right,” says R-mode, “it’s just shaped differently from a “standard” one because its wrist is farther away from us than its fingers.”

Edwards wrote (p. 178),

“R-mode apparently computes instantaneously and nonverbally…. This computation – and the size-change information that hits the retina – is somehow kept ‘secret’ from conscious awareness, perhaps in order not to interfere with or complicate the language system.”

I suspect this instantaneous computation is also “kept secret from conscious awareness” because language – the currency of L-mode – would slow down its lightning speed. The rapidity with which our R-mode calculates that a flesh-colored circle is a finger pointing at us happens far faster than we could ever describe in words.

An analogy that might make this clearer is of an athlete hitting a ball. The athlete’s R-mode brain is making calculations at phenomenal speed about how far away the ball is, how fast its moving, where its moving, and about how the athlete him/herself must move and react to all that information in order to successfully connect with the ball. If the athlete had to bring all of this to consciousness and calculate it verbally – “the ball is now curving right and I can see it will bounce in this particular way, so I calculate that I should move this way – no, I now see that it had spin on it, so I need to redo my computations…” – the athlete would never be able to hit the ball before it went whizzing past.

Bringing the aha to more readers

When artists draw, I believe they are making judgments and decisions at that same lightning speed as the athlete hitting a ball. Their thought process has to be non-verbal because of the countless calculations made in a split-second’s time.

I think this is why it’s so difficult to convey drawing instruction in words. The artist’s observations, judgments, and decisions happen in a split second of often-exciting non-verbal discovery. But to convey to a reader that same thought process takes long paragraphs of verbiage. That’s why I’m hoping to be able to get more video drawing demos up on this blog in future – along with text that tries to convey a small fraction of the artist’s split-second decision-making as he or she works.

We need language to communicate the artist’s process to other people. But language is slower and more reductionist than some other processes in our brains. Hopefully a combination of images, video, and language will bring the aha moment to more readers of this blog in the future.