“The face is the primary signal system for showing the emotions”

This spectacular painting by American portraitist Simmie Knox (most famous for painting the official Presidential portraits of Bill and Hillary Clinton) is, to me, one of the ultimate role models for the creation of profoundly humanistic portraits. The expression of pride and suppressed merriment in Mrs. Irondell’s face conveys so much more than if she had been painted in a traditional pose gazing into the middle distance. Her clothing and surroundings express elegance and wealth as well as any more formal portrait, but the look on her face – and that of her mischievous granddaughter – raises this portrait far above the standard pose.

To capture this kind of expression in a painting is no easy matter. To begin with, it’s impossible for a subject to produce an expression like this on demand while an artist paints. I don’t know how Knox created this portrait, but it’s hard to imagine he didn’t look at photographs to help. (To read my earlier entries on photography, click here.)

In addition to photos, there’s another resource that can help in painting human expression. The human face generates expressions via many different muscles functioning together under the particular flesh of each person. So for an artist to paint expressions, it’s important to have a working knowledge of the basic facial movements that create them.

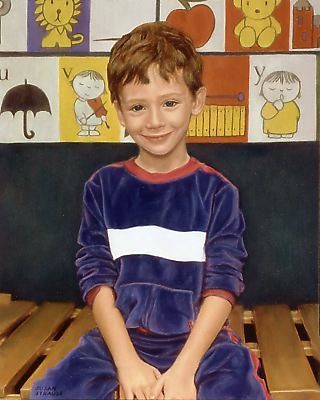

Because my own central aspiration in portraiture is to learn ever more about how to fully convey human expression, I’ve relied on THE ARTIST’S COMPLETE GUIDE TO FACIAL EXPRESSION, by Gary Faigin. This book analyses the myriad movements of facial muscles which construct the expressions we recognize as joy, fear, anger, disgust, surprise, sadness, and various nuances of these emotions. In a future blog post, I’ll describe the crucial role Faigin’s book played, for example, when I faced the challenge of painting an impish little boy based on a terribly over-exposed family photograph.

In addition to my trusty copy of Faigin, my daughter Nastassia Hajal, a Ph. D. student in Child Clinical Psychology at Penn State, recently introduced me to another book about facial expression: UNMASKING THE FACE, A GUIDE TO RECOGNIZING EMOTIONS FROM FACIAL EXPRESSIONS, by Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen. It’s used by psychologists researching e. g. mothers’ emotional responses to their babies. (I later discovered that Faigin himself had utilized Ekman and Friesen’s work in his ARTIST’S COMPLETE GUIDE.) Ekman and Friesen’s roughly 45 years of research on human expression have been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

But why should portraitists bother studying movements of muscle or flesh or anything else? Isn’t portraiture about stillness? Don’t portraitists almost always paint their subjects in repose, sitting as motionless as humanly possible for the painter? Why not leave facial expression to other kinds of artists who deal with that sort of thing?

My emphasis on human expression in portraiture is not the traditional view, nor is it widely accepted today as the primary goal of portraiture. Much of the accepted “wisdom” about expressionless portrait subjects is based on our collective image of a person posing immobile for hours while an artist paints them – an image which is no longer generally true because most portraitists nowadays work from photographs. But one way or another, there are portraits created which – like the ones we will look at below – capture uniquely wonderful facial expressions.

To me, the most miraculous aspect of the individual human face isn’t its surface appearance, but its capacity to convey true human emotion as nothing else can – not words, not any other part of the body. Ekman and Friesen note that many professionals such as trial lawyers must learn to focus on visual signals from the face because words can lie while faces usually cannot.

Both facial expression and words, wrote Ekman and Friesen, are used for communicating information among people.

“Words are best for most messages, particularly factual ones. If you are trying to tell someone where the museum is, who played the lead in that movie, whether you are hungry, or how much the meal costs, you use words….

“Words can also be used to describe feelings…. Here, however, the advantage is with the visual channel, because the rapid facial signals are the primary system for expression of emotions. It is the face you search to know whether some one is angry, disgusted, afraid, sad, etc. Words cannot always describe the feelings people have…. If some one tells you…he is angry and shows no evidence facially, you are suspicious. If the reverse occurs and he looks angry but doesn’t mention anger feelings in his words, you doubt the words but not the anger.” (18)

If emotion is better expressed visually than through words, how about the rest of the human body? Do we see emotion expressed through movements of the body’s muscles?

Ekman and Friesen’s research shows that emotions “are shown primarily in the face, not in the body. The body instead shows how people are coping with emotion.” The body might be tense, constrained, withdrawn; it may attack physically. But none of these body postures are unique to particular emotions. Ekman and Friesen wrote, “The face is the key for understanding people’s emotional expression, and it is sufficiently important, complicated, and subtle to require a book to itself.” (7)

Well, if facial expression is the primary locus of the most truthful emotional communication among people, shouldn’t it be the territory of portraitists? The human face is our turf! Now that photos help make it possible to paint fleeting expressions, we portraitists can move into this territory and stake our claim to it. The face holds the key to the highest peak of human experience. Why should portraitists – specialists in the face – cede its expression to other artists?

Now that I’ve vented on that subject, let’s see what insights Ekman and Friesen give us into Knox’s portrait. Here is is again:

What do the body positions of each subject in Knox’s portrait convey about how they will handle the emotion expressed in their faces? As we’ve said, Mrs. Irondell’s face conveys delight and pride, a sense of fulfillment in a life well lived. And what does her body tell us she will do about those emotions? Well, her arms quietly dominate the chair as they rest there. And her completely relaxed, non-erect body posture tells us she’s not going to do – doesn’t have to do – a damn thing but enjoy herself! This relaxed yet dominant body posture conveys a sense of life achievement as much as do her rich surroundings and expensive clothes.

Her granddaughter doesn’t yet dominate the piece of furniture she rests her arm on – it’s almost bigger than she is. But her mischievousness as she hides behind her grandmother clearly dominates Mrs. Irondell’s heart. The smile on the little girl’s face tells us she’s having fun sneaking up behind her grandmother. Mrs. Irondell is having a ball knowing perfectly well she’s there. The two people are fully aware of each other, able to relate intensely even though they aren’t facing, because they know each other so well. (Their close relationship is conveyed also by their hats, identical except for color.)

In this painting, Knox has captured expressions that may be fleeting, but in so doing, he has expressed the profound essence of the relationship between Mrs. Irondell and her granddaughter.

Let’s look at another portrait, this one by Colorado portraitist Judith Dickinson, which also captures a delightful facial expression combined with unique body posture.

This is one of the most charming portraits I’ve ever seen of a child. It captures something deeply true about childhood. The little girl’s eyes are somehow both dreamy and alert. Her chin is tilted up with gentle expectation and an unassuming sense that good things are ahead in her life.

What can we read in Olivia’s body about what she will do about the emotional expectations we see in her face? The very specific position of her arms, hands, and body gives me the sense that she has just sighed with contentment before settling into this pose. She is very relaxed, suggesting that she will move at her own pace and in her own time toward life’s pleasures. She is oblivious to the fact that her pretty dress is slightly twisted, in the way all children’s clothing is. Her feet don’t reach the ground, but she’s not wriggling to get them there.

(And harking back to my earlier post, Portrait Composition: Old World vs. New? – click here – the use of empty space above and beside the little girl adds tremendously to the feeling both of her smallness in the world, and of her sense that good things will come in their own time. They aren’t here yet – the space is empty for now – but her relaxed expectation tells us she feels they will come and make her life good.)

Even official portraits can have wonderful facial expression. In this portrait of Carmel O’Sullivan, Dean of Women Students at University College Dublin, the face radiates intelligent warmth. The twinkle in O’Sullivan’s eyes makes me feel she’s the adult I’d want turn to if I were a student with a problem. One could imagine no better quality than this in a portrait of a college dean.

What is O’Sullivan’s body showing about how she will deal with the emotion her face exudes? She is opening the door into her office, welcoming us in. Facing us all the while in her cheery outfit, she’s alert and ready to help. She’s holding a couple of books in her hand, including one about Rembrandt, conveying the sense that she will bring intellect and culture to bear.

To me, this painting expresses so much more about the relationships this Dean has with her students and peers than would a formal portrait in a traditional official pose.

Below are several more portraits that accomplish beautifully the portrayal of unique personal facial expression. You can click on any image to see a larger version on the artist’s website. I’ll leave the fun of analyzing these to you!

For myself, I hope that looking at these unusual and very special examples will help me learn to portray ever more complex and singular expressions in my own paintings.

Note: Please see Postscript for a wonderful interchange I had with Judith Dickenson on her painting of Olivia (above) after completing this post.

Ann, Countess of Yarborough, by John Ward