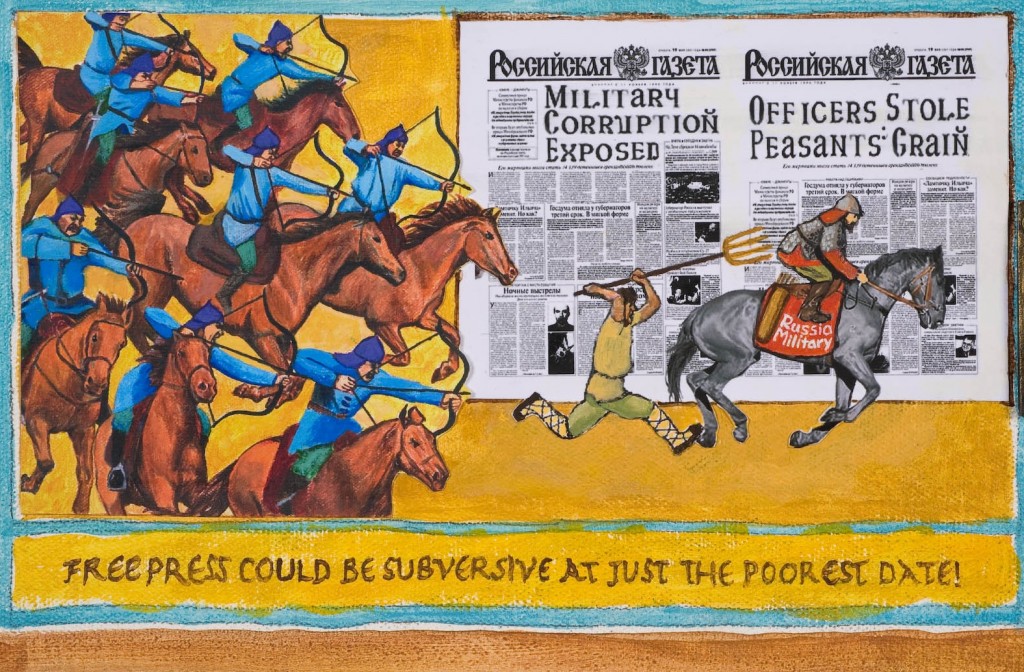

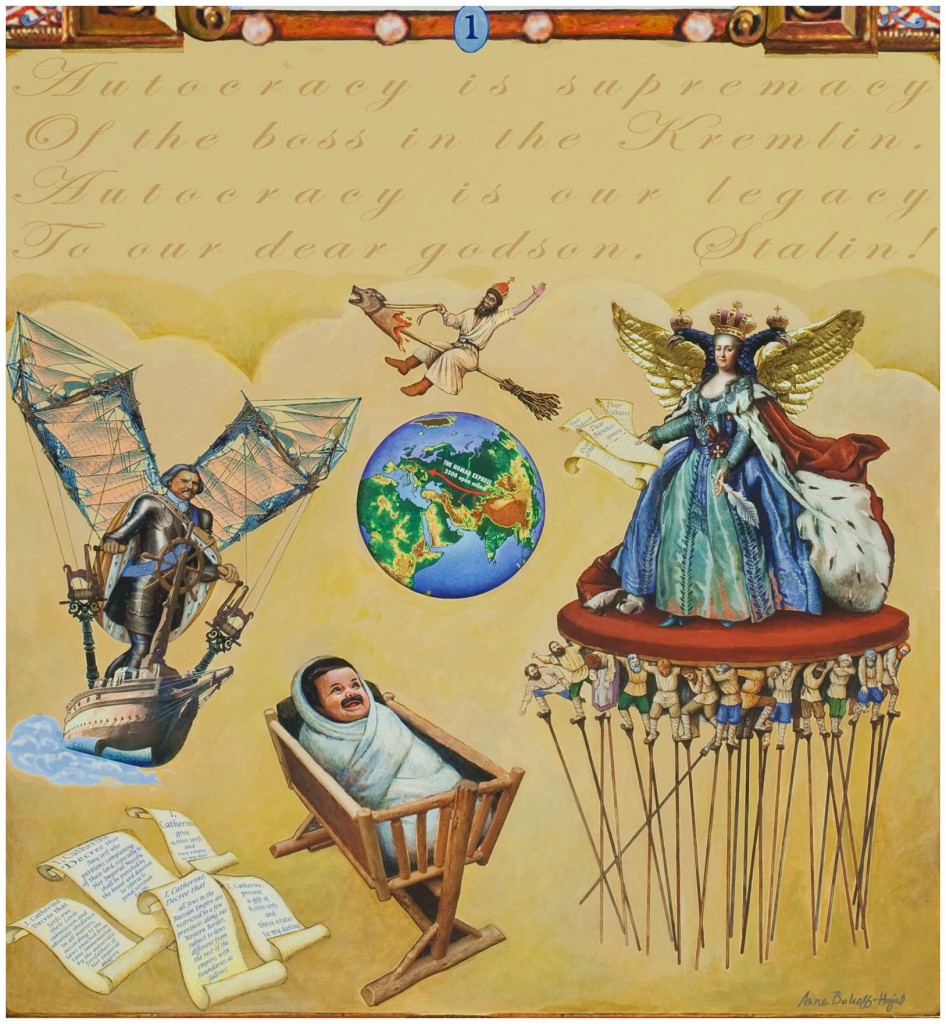

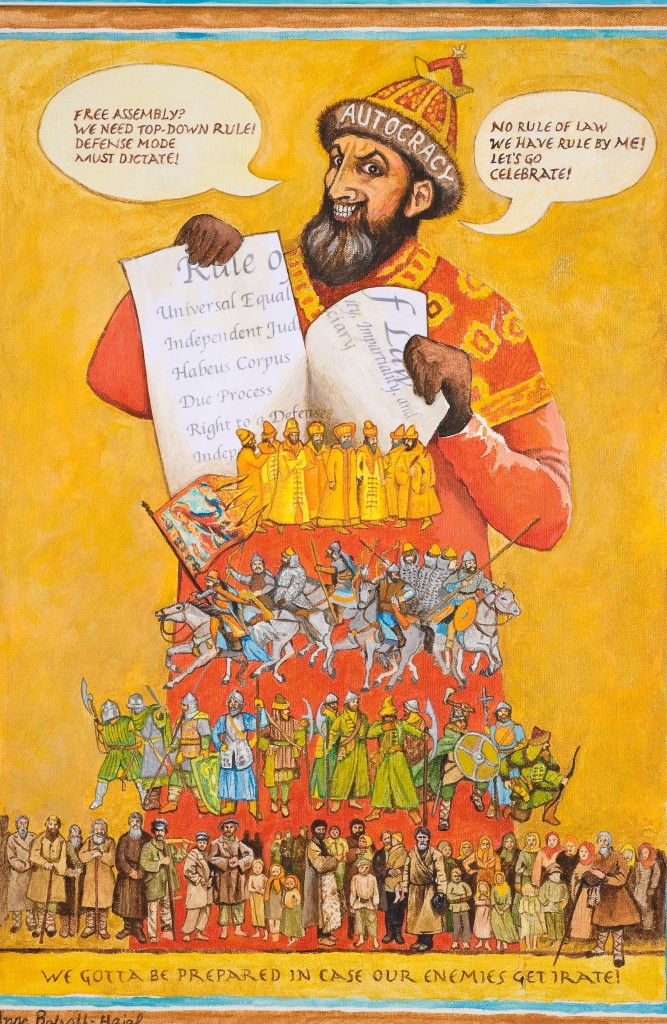

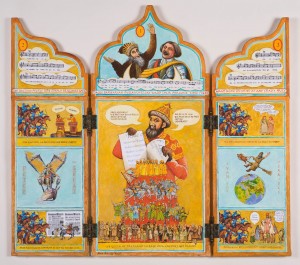

Two PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS main characters, Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, sing about the glories of autocracy. Detail from "Home Security At Any Crazy Price"

This is the second in a series of lively, fun, and challenging study guides illustrated by my artwork about Russian history. (The first, Introductory Study Guide is here).

In addition to being an artist, I have a Ph. D. in Russian History from the University of Michigan. My new paintings and mixed media works about Russia are collectively titled PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS.

_____

“Big Questions” to think about as you study:

A. Was Russia forced to expand to take over the southern steppes all the way to the Black Sea in order to protect its people from constant Tatar invasion and slave raiding?

"Home Security At Any Crazy Price," by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 36" x 40" . 2009

B. Or was Russia greedily expansionist, grabbing up territory it wanted rather than needed to protect its people? Could Russia have built a single strong defensive “Great Wall of Russia” effectively enough to block all Tatar incursions, rather than multiple “Great Walls” ever farther south?

Food-for-thought questions:

C. Might the Tatars have had other choices than slave-trading and raiding to support themselves? Why were slaves so widely used at that time, including by the Ottoman Empire?

D. Are the Tatars and Ottomans the bad guys in this saga, and the Russians the good? Is reality more complex than that, or is this a clear cut case of good vs. evil?

You won’t be able to answer these questions now. But think of them as mysteries and yourselves as detectives. As you learn more, look for clues that may help you form your own opinions.

Russia’s Military History on the Endless Steppe

If you want to understand Russia, you need to be able to picture its massive expenditure of resources and human lives – for nearly its first five centuries – to protect against invasions and slave raids across its southern steppe frontier. Russia contains the largest expanse of flat land on earth. There was very little natural protection on the vast plains between Russia and the Black Sea. In the southern grasslands, there weren’t even forests to hinder invaders. Russia therefore had to create a man-made defensive system to protect its immense open frontier. (Continued below image)

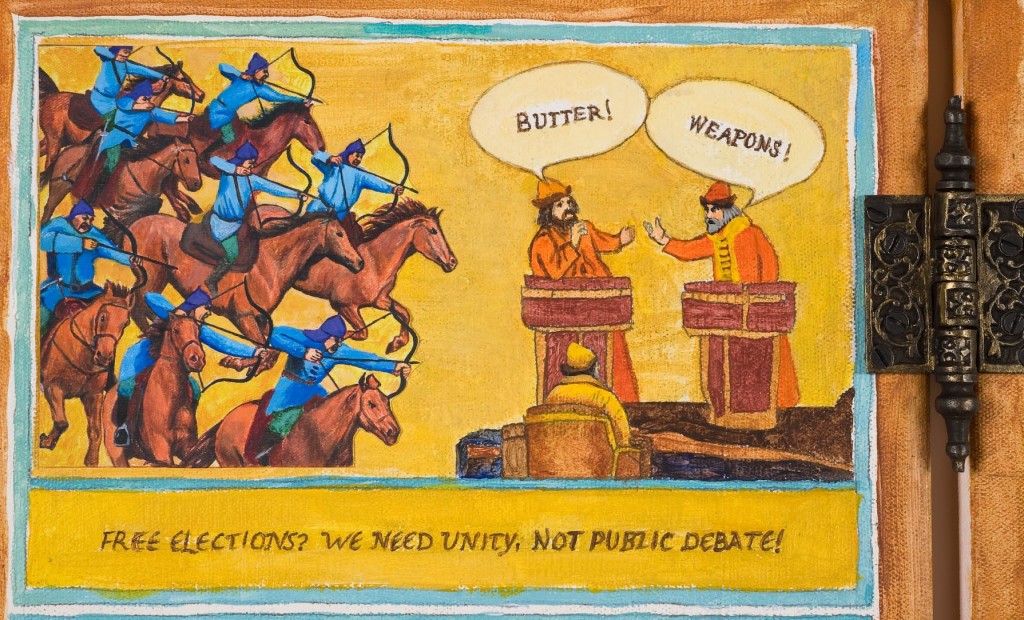

Detail of left panel, "Home Security At Any Crazy Price," by Anne Bobroff-Hajal . Acrylic paint and digital images on canvas and board . 36" x 40" . 2009

When we envision Russia’s military history, we often think of its wars with European and Baltic nations to its west or of Russia’s rapid expansion across Siberia.

But at least as important in shaping Russia’s government and society was its southern frontier. This frontier was perhaps unique in all the world in its vast size, combined with its nomadic Tatar inhabitants who lived largely by raiding and slaving, partly to supply the powerful Ottoman Empire next door to them.

Why Have Many Westerners Paid Little Attention to Russia’s Southern Frontier?

Americans and other Westerners may tend to focus on Russia’s eastern and western wars because we identify with them. European neighbors were Western, like ourselves. And Russia’s expansion across Siberia mirrors US pioneering expansion across our own western frontier. In short, we have points of reference in our own experience for Russia’s battles with populations to its east and west. (Continued below image)

But for the US, there is no parallel to Russia’s southern border. Over half our southern limit is formed by water: the Gulfs of Mexico and California. The single country bordering our south, Mexico, was far less powerful than the Ottoman Empire and its client Tatar khanates.

So we have no point of reference for Russia’s south. It’s not easy for us to wrap our heads around the implications of the largest expanse of land on earth without natural barriers to prevent constant incursion and annual “harvesting of the steppe,” the abducting of hundreds of thousands of Slavs sold into slavery in the powerful neighboring empire (Ottoman).

Let’s try to give ourselves some points of reference to help us picture Russia’s centuries-long struggle to make its southern population safe along this vast open frontier.

Southern Russia’s Garrison Towns

Brian L. Davies book cover

Most towns in southern Russia were originally founded by Moscow as garrisons designed to protect against invasions and raids. Towns couldn’t rise on the steppe organically, based on trade or agriculture, because a settled conglomeration of people would be an immediate target for Tatar raiders. Towns could exist only if the central government built a garrison, with troops to protect it and patrol the surrounding wide open plains. For example, in 1677-8, “the southern regions mustered the largest number of town servicemen ever, nearly 47,000 in seventy-three cities.” (Stevens, p. 127).

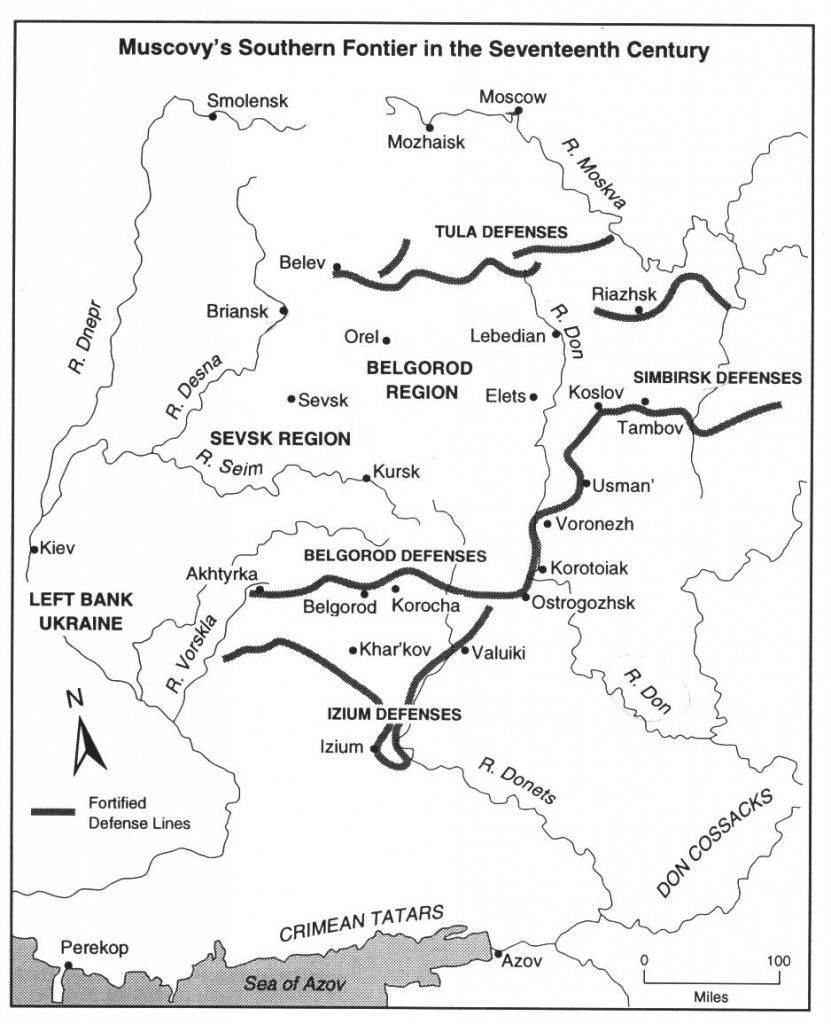

The “Great Walls of Russia”

As early as the 15th century , the Russian government began constructing a series of what have been called “the Great Walls of Russia,” each several hundred miles farther south in the steppe. These lines were a combination of fortified towns, stockades, earthen ramparts, trenches, guard posts, and mobile patrols.

Brian L. Davies describes a section of the Belgorod Line, a 25 km earthen wall built by 950 laborers in 5 months:

This wall stood nearly 4 meters high and had seventy bartizans [overhanging turrets], four earthen forts, breastworks, and ditch and anti-cavalry fences.

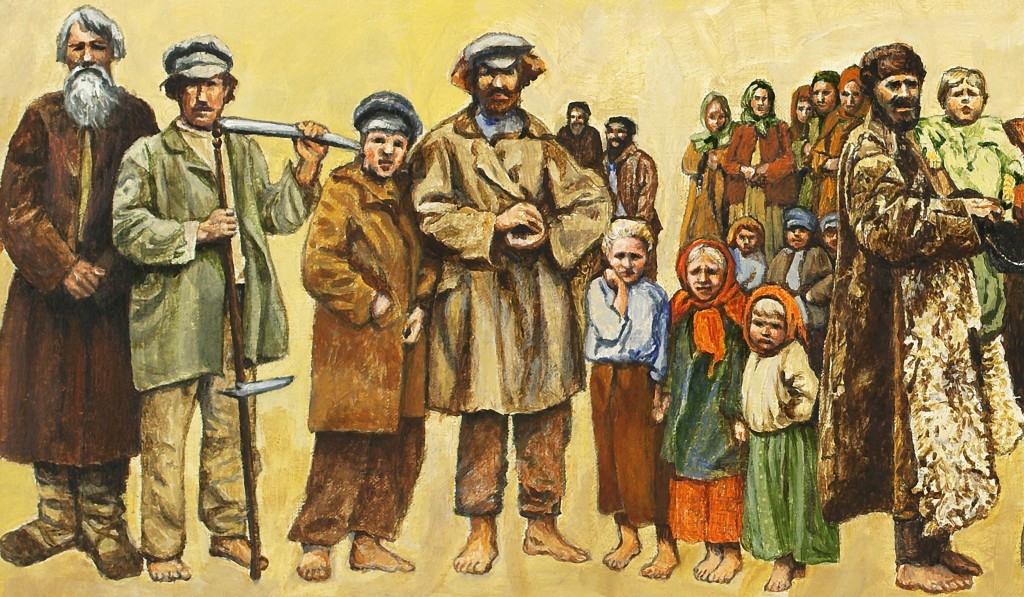

Who Lived on the Steppes and Patrolled the “Great Walls?”

There were very few peasants living and farming on the southern plains because they would have been too vulnerable to raiders. (Continued below image)

So to create a population to guard Russia’s defensive lines, Moscow sent recruits to the frontier, providing them with plots of land near garrisons to farm for their own livelihood and for taxes. Carol Belkin Stevens (Kira Stevens) has done brilliant research into the lives of these people for her Soldiers on the Steppe: Army Reform and Social Change in Early Modern Russia. If you’re writing a term paper on this subject, her book is a must.

Daily Lives of the Frontier Garrison Army

Garrison servicemen were responsible both for guarding their forts and for patrolling the long defensive lines snaking out from their towns. Constant vigilance was needed to spot fast-moving, skilled Tatar raiders moving across the steppe. For example, writes Stevens, in the town of Valuiki,

Seventy mounted steppe patrolmen left the fortress at six-day intervals from late spring through early fall. Their tour of the steppe was extensive…watching for signs of Tatar approach…. Mounted servicemen patrolled between outlying towers or small fortresses and into the distant districts. Cavalrymen in shifts of six relayed any messages or goods locally; sometimes they provided escort and protection to officially sanctioned groups traveling toward the lower Don. Beyond the frontier they also stood guard over work on distant and exposed fields or carried news of imminent attack to outlying villages…. Closer to Valuiki, fifty mounted [troops] patrolled the towers of the fortress….

Warnings of imminent Tatar attack led to general alerts, and town walls were manned more densely – often by garrison servitors from other towns. Musketeers and hereditary servicemen escorted criers with news, orders, and calls to arms around the province. (Stevens, p. 131-2) (Continued below image)

In addition, these servicemen repaired old and built new fortification lines. For example, the southern-most Izium line was constructed by 30,000 men over several years. “Anticipated Tatar attacks during the construction of the Izium wall placed nearby garrisons on alert, even while town servicemen from further north were actively engaged in building.” (Stevens, p. 133-4).

Provisioning Garrisons and Campaign Armies over Vast Distances

Carol Belkin Stevens book cover

In addition to supporting themselves on their own farm plots, southern servicemen were required to contribute grain for the support of campaign forces and people constructing new defenses farther south. They were responsible for carting this grain themselves to central storage depots, which could be a hundred miles or more away. Servicemen had to build granaries, warehouses, and river boats to move grain southward; they also worked on the docks. “Because old boats could not easily be returned upriver, the gathering of labor, materials, iron parts, and the selection of loaders, escorts, and rowers were annual events (Stevens, p. 134-5).

In the context of continual danger from the south, only a powerful central government could mobilize such massive efforts, and squeeze such great resources and labor from its people.

Stevens gives an amazing description of the first attempt to move campaign troops across the entire steppe to try to do battle with the Crimean Khanate on its own stronghold:

…the army and its supplies were a nearly unmanageable mass…. The massive army led by Prince Golitsyn proceeded slowly across the steppe. It was organized with an advance guard of ten regiments, followed by a long rectangle made up of an estimated one hundred regiments and the supply train. In that long rectangle, the main infantry forces surrounded a moving barricade of 14,000 horse-drawn carts that were arranged in ten rows and flanked on the sides by 6,000 more carts in seventeen parallel rows. The front and flanks of this oblong – 2.3 miles across and 1.2 miles long – were protected by cavalry, with the artillery bringing up the rear.

[At best] the army would have needed more than two and one-half months of any summer campaign to reach…the Crimea and return. In addition, any such venture required the availability of at least some food, water, and wood along the route….

By 1687 Muscovy could, by exerting extraordinary organizational effort, successfully gather more than enough food for that part of the 112,000 man army it chose to supply. Russian campaigns against the Crimea, however, posed unusual problems in the disbursement of supply to a large army. Elsewhere in Europe, similar disbursement problems would be resolved partly by reliance on local agriculture and partly by a series of provision magazines, at regular and quite short intervals…. Neither option was available for the Muscovites proceeding across scantly populated and hostile steppes against Crimea. (Stevens, p. 119-20; my emphasis)

In fact, Golitsyn’s army was never able to reach the Crimea. “The Tatars had burned the grass of the open steppe; to cross that territory, the army would have had to invest enormous effort searching for fodder for its more than 100,000 horses.” They had to turn back homeward without ever seriously engaging the enemy.

It would take almost another century before the Crimea was conquered, by Catherine the Great.

More on the Tatar Enemies

Brian L. Davies and Kira Stevens have done all-important research on Russia’s extraordinary southern struggles, each from a different perspective of the Russian side. The terrific work of Michael Khodarkovsky, published in Russia’s Steppe Frontier, The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500-1800 (in an Indiana-Michigan series, one of whose two general editors was my UM advisor, William G. Rosenberg), in addition gives more of a sense of the Tatars the Russians battled against.

This trio of books is essential reading for anyone studying Russia’s south. In fact, given the importance of the south to all of Russian history and the shaping of its society even today, these books are important for anyone studying Russia period.

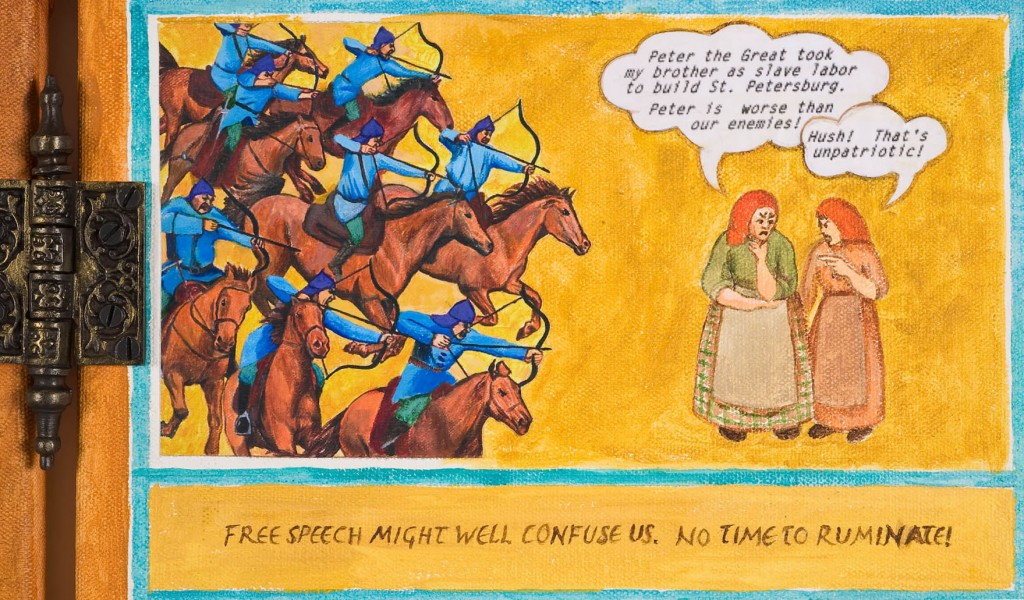

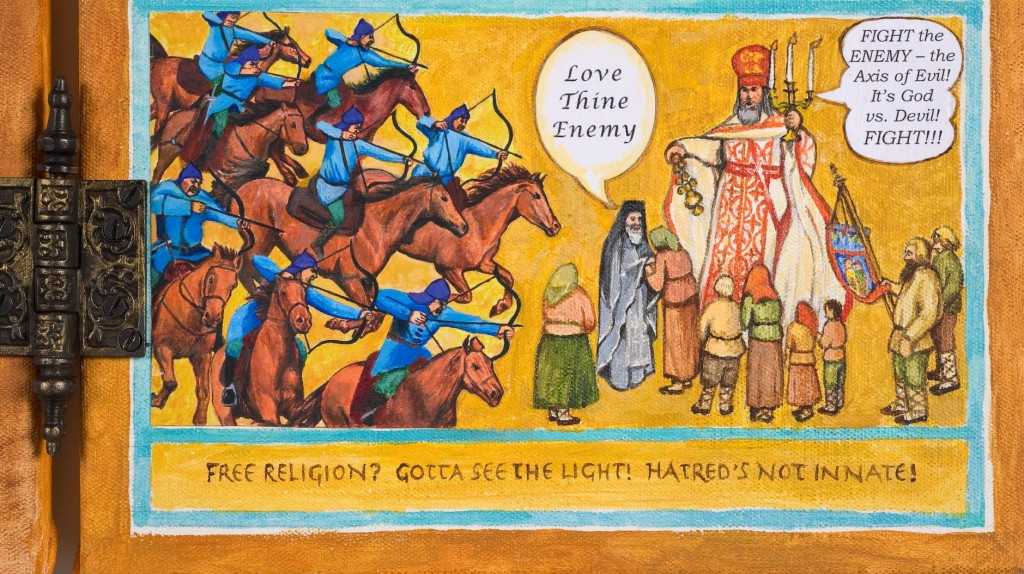

My icon-like Playground of the Autocrats artwork

My PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS artwork plays whimsically with the serious saga of the impact of Russia’s peculiar defensive dilemma on its government and society. I believe that Russia’s autocratic government arose in response to the military struggles described in the work of Davies, Stevens, and Khodarkovsky. Russian society was organized as a military chain of command, with no independently-organized power bases. For five centuries, the entire country was ever-prepared to fight against the raids and invasion which came multiple times virtually every year. And Russia’s rulers took full advantage of its people’s desperation, building what Ronald Wright called a protection racket.

For more on PLAYGROUND OF THE AUTOCRATS, please see the article recently published by Terrain.org, A Journal of the Built and Natural Environment, as well as other posts here. A PLAYGROUND triptych, “Home Security At Any Crazy Price,” was described by the New York Times as “an homage to Joseph Cornell…full of wonderful goodies.”