This is Part 2 of the description of a creative process. To read it in chronological order, please read Part 1 first.

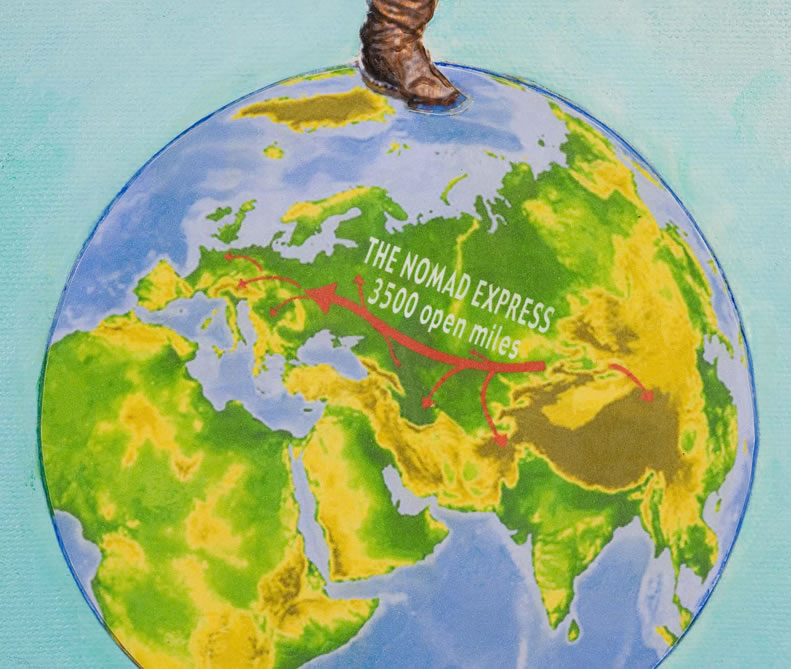

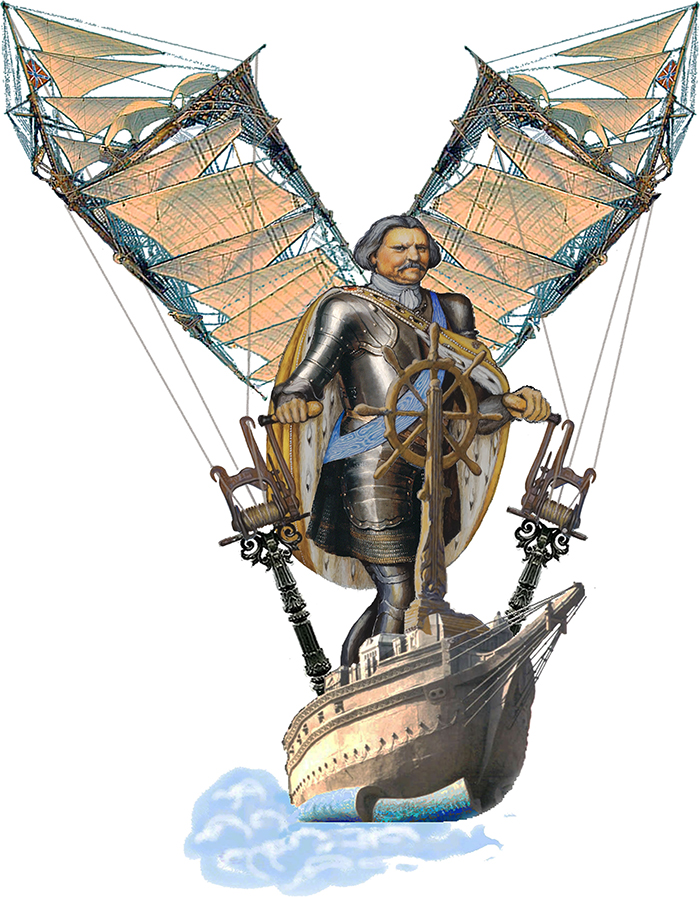

At the end of my last post, I presented icons and Russian folktale illustrations each of which had a central image framed with secondary images that added to its meaning. Below is a detail of the center panel of my triptych The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth. It shows the way in which I used the image-frame technique to help resolve my own challenge: to convey the endlessness of the flat Russian steppes, 3,500 miles wide.

Detail: Center panel of triptych The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth

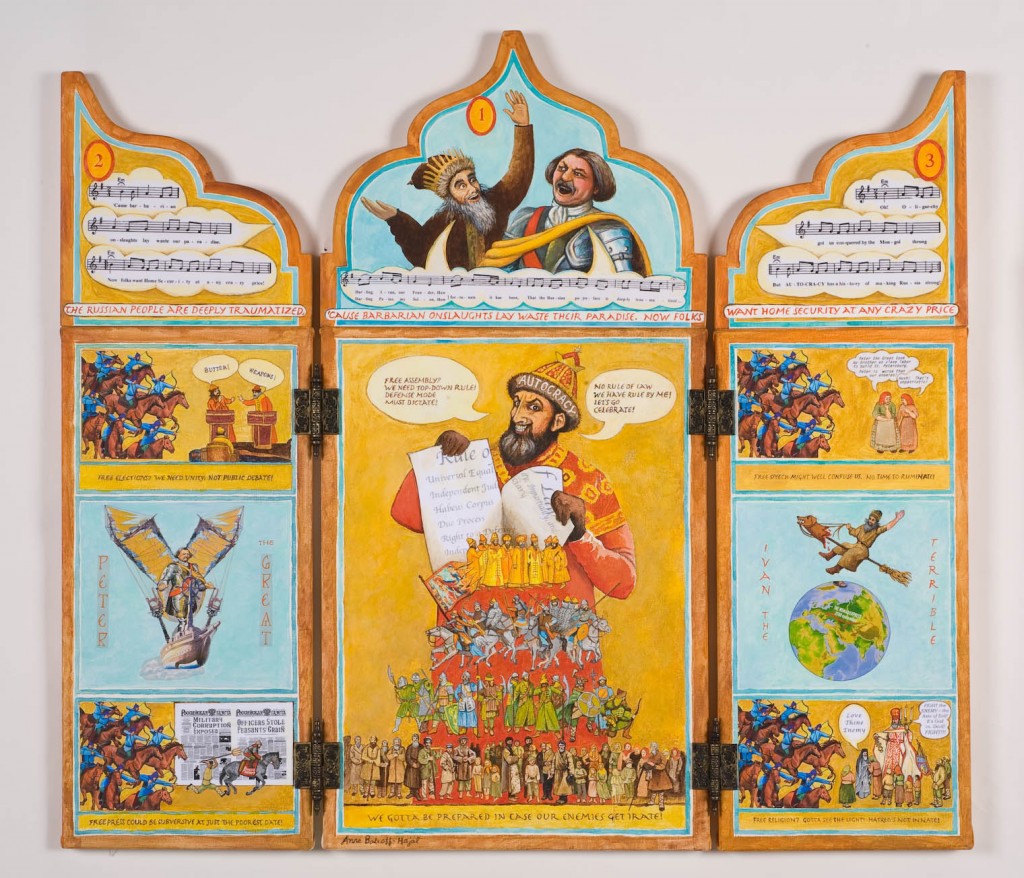

My frame is a collage of landscapes by 19th century Russian painters. These painters were collectively known as the Peredvizhniki (usually translated into English as either the Wanderers or the Itinerants). Many of their most famous works portray the Russian steppes. Through the repetition of these beautiful images of the land, I hoped to help convey the vastness of Russia’s flatness.

There is a deeper emotional level to this collage than the purely informational one. The Peredvizhniki may not be household names in the US, but they certainly are in Russia. They are to Russian art what the great Russian novelists are to the country’s literature. The Peredvizhniki are profoundly Russian. They are of the land. The Russian people feel their work deeply, and identify with it. These paintings hold all the love and sorrow and suffering of the Russian people over the long course of their history.

Detail, center panel, The Most Exposed Terrain on Earth

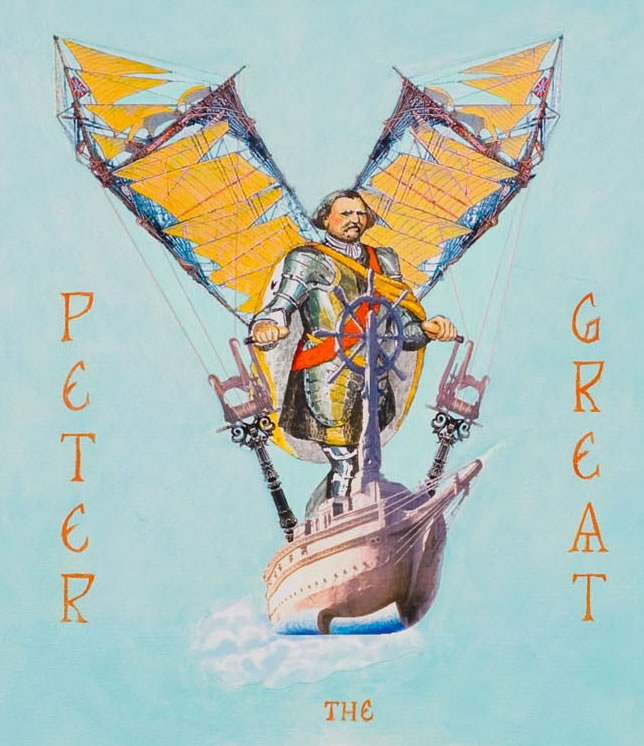

My own goal as well with Playground of the Autocrats is to embrace all the aspects of human life: knowledge, pain, joy, satire, humor, suffering. Close examination of many of the figures in the crowd scenes in Playground reveal attention to the many sides of human experience.

I’ve never been able to understand why the Peredvizhniki aren’t better known in the United States. Some of their paintings were shown in the Guggenheim’s Russia! exhibit several years ago. Elizabeth Valkenier, Columbia University’s Russian art expert, has published several books about them, such as the the terrific The Wanderers, Masters of 19th Century Russian Painting. And there’s a wonderful book by Mikhail Guerman, The Russian Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

But the Peredvizhniki are much less widely known here than are the European Impressionists. My use of their paintings in my frame is my homage to their greatness.

In my next post, I’ll get to the music and lyrics of Playground of the Autocrats.